Princeton Portrait: The ‘Girl Reporters’ Who Got Their Scoops

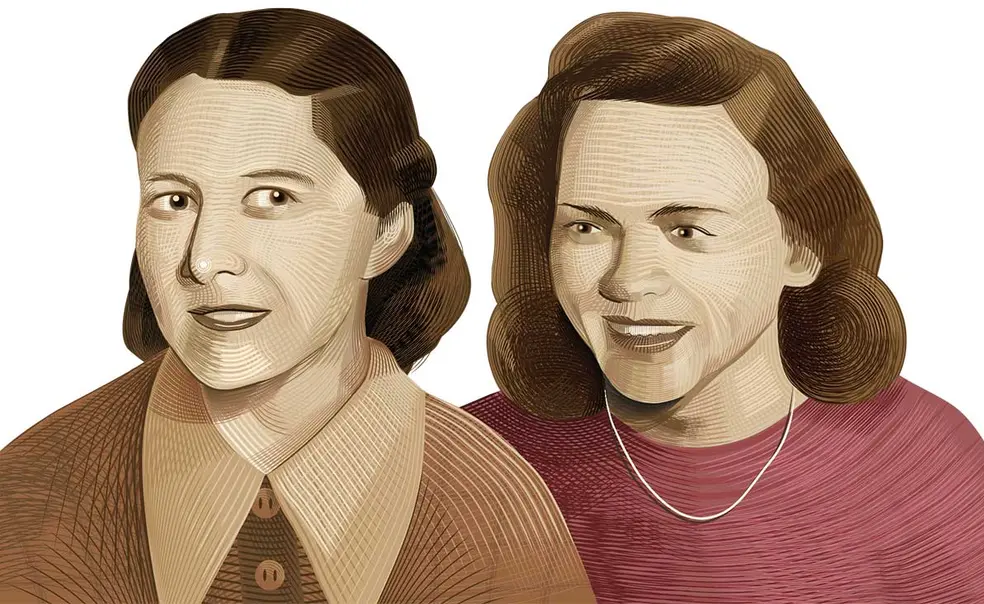

Princeton Portrait: Doris Orth Pike (1923–1996) and Ruth Flavin Donnelly (1919–1991)

In 1946, The Daily Princetonian ran an unusual headline: “Girl Reporters Join ‘Prince’ News Staff.” Doris Pike and Ruth Donnelly, the wives of Princeton students who had returned from the war to finish their studies, had begun to collaborate on a column that reported on married life at Princeton. The Princetonian already had the basic lumber of a newspaper office: hard-nosed editors, mild-mannered reporters, copy-desk chiefs, the rat-a-tat-tat ka-ching of typewriters, a telephone, a dictionary, runners to rush drafts to the letterpress printing office in town — but after 70 years, it finally had the element that every great newsroom needs: intrepid girl reporters to serve up hot scoops.

Pike and Donnelly had a lot to report on. They learned about the hidden lives of the 90-odd student wives living on campus, as other Princetonian reporters seemingly had been afraid to do. (The column got its start, they wrote, when they saw a student “hovering nervously” outside Brown Hall, which was home to many married couples. When they approached him, he blurted, “We want a column on married life at Princeton from the wives’ standpoint.”)

Some of the women had been spies, medics, or servicewomen in the war: Doris Bernabei and Norma Kerr served in the Navy, Anne Chamberlin served in the Office of War Information in Egypt, Joan Robinson served in Britain’s Auxiliary Territorial Service, Barbara Betts worked for the Red Cross, Patricia Lathrop held the rank of lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps, and others — whom Pike and Donnelly discreetly left unnamed — worked for the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime predecessor to the CIA. Still others built engines and calculated ballistics for aircraft and arsenal factories.

Keeping house at the University required ingenuity. A waffle iron, a gas can, and a hot plate had to provide such home cooking as the clever chef could devise. Wives did the cooking, shopping, cleaning, and typing, and about a third of them worked in town as researchers, teachers, shop clerks, secretaries, or nurses. They sat in on courses at the University when the instructors gave permission. (Pike and Donnelly published a list of courses that departments had given blanket permission for women to audit.) Many instructors got used to the new faces in their classrooms and even found a new source of vanity in comparing how many “voluntary listeners” they could draw. “One department came up with the idea that wives could not be permitted to attend one of their lectures,” Pike and Donnelly wrote, “for the lecturer was too young and handsome.”

Graduates of Middlebury (Pike) and Wheaton College (Donnelly), the reporters were wry, sly, good-humored observers of domestic life in the dormitories. In time, they wrote, men became almost inured to seeing women on campus paths. Their spouses, James Donnelly ’43 and Otis Pike ’43 (who became a New York congressman), were veterans of the Army Air Corps and the Marine Air Corps, respectively.

“In closing,” the women wrote in one column, “we would like to reassure the Sons of Princeton ... that the womanhood on Tiger territory will be removed as soon as we can tutor our husbands through, but in the meantime, that womanhood will go on having a mighty good time.”

No responses yet