He Founded ‘The New Yorker’ and Gave It a Second Chance

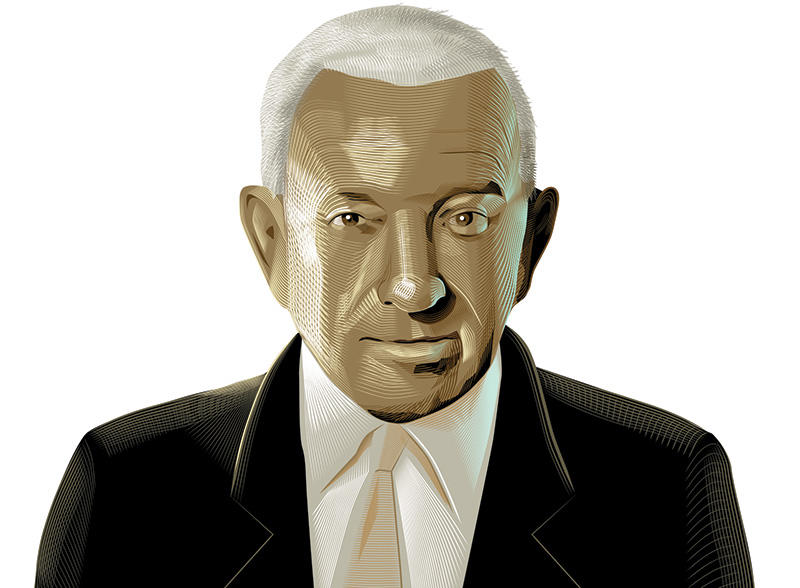

Raoul Fleischmann 1906 (1885-1969)

How does an editor read? Teachers drill their students in thesis statements, arguments, structure, and evidence, but correspondence between editors often reveals quite different preoccupations. One word can provoke fury. (In 1954, Arthur Hays Sulzberger of The New York Times wrote to the paper’s managing editor, “In our nine o’clock bulletin Sunday night we used the word ‘climax’ as a verb. We said something ‘was climaxed’ which had to do with Senator Sparkman. Will you please kill the man who did it?”) Or a whole piece can sink or sail on the imponderable criterion of tone. In the early decades of The New Yorker, editors would give submissions appraisals — fluffy, elliptical, sprightly, worldly — that a composition teacher would struggle to explain. At their level of the profession, they could take the building blocks of a story for granted, which left the lightning-flash recognition, and appraisal, of style:

“Fine piece. Exactly right for Wooley: the very worldly approach, the proper fluffy texture, some laughs, and as much solid information as you want about the man.”

“This interested me. A curious, out-of-the-way story, although [the writer’s] telling of it tends to be cloudy and elliptical, and he doesn’t make the liveliest possible use of his material.”

“Good piece, I think. As she notes, it’s not terribly funny, but it’s light and sprightly and, to me, informative.”

Fleischmann was the magazine’s shadow reader, a model to be imitated and gently scandalized.

The style of The New Yorker itself — arch, assured, literary — owed something to Raoul Fleischmann 1906, the magazine’s founder and president. Its editors boasted of freedom from the business department, but in fact they tried to live up to the business department, like an aesthete trying to live up to his china. The editor-in-chief, Harold Ross, was not rich, and he seemed to test ideas against Fleischmann, who was. (“We are going to cover all the gentlemen’s sports there are,” he said: college rowing, polo, tennis, yachting, anything with athletes named Winnie or Julesy or Trip.) Ross also tried to “raise the tone of our contributors’ surroundings, at least on paper”: to prevent their mentioning “having their telephones cut off, or not being able to pay their bills, or getting their meals at the delicatessen.” Eventually he chilled out, and The New Yorker found a tone that balanced the self-assuredness (and attendant self-deflating irony) of the college-rowing crowd with raffish slang and an outsider’s lurking skepticism. Fleischmann was the magazine’s shadow reader, a model to be imitated and gently scandalized.

Fleischmann attended Princeton for just one year; but at the time, setting foot in a classroom was enough to ensure alumni status, and he appeared in alumni directories for life. The heir to Fleischmann’s Yeast Co., he took a chance on Ross, who asked him in 1924 to invest in a new magazine. In 1926, the Class of 1906 announced in PAW, “Raoul Fleischmann, who was with the Class through freshman year, is head of the new weekly, The New Yorker, which has made such a hit as a smart journal intended for the sophisticated who want to know what is going on in the metropolitan mind. Fleischmann showed great nerve in launching the magazine, and the cleverness with which it has been edited and promoted has already established it in a little over a year as an outstanding success in magazine publishing.”

The magazine would have gone under if not for a meeting at the Princeton Club in New York City. Publishing is a money pit, and in May 1925, Fleischmann, frustrated that the magazine, then three months old, was pulling $5,000 a week out of his wallet without turning a profit, resolved to end his support. He booked a table at the Princeton Club with Ross and two other employees, John Hanrahan and Hawley Truax, to tell them the bad news. “Leaving the club, the four of us started walking up Madison Avenue,” he later said. “It was at 42nd Street, during a traffic lull, that I heard Hanrahan say to Truax or Ross, behind me, ‘I can’t blame Raoul for a moment for refusing to go on, but it’s like killing something that’s alive.’”

The comment “got under my skin,” Fleischmann said. He stayed, and the magazine thrived.

0 Responses