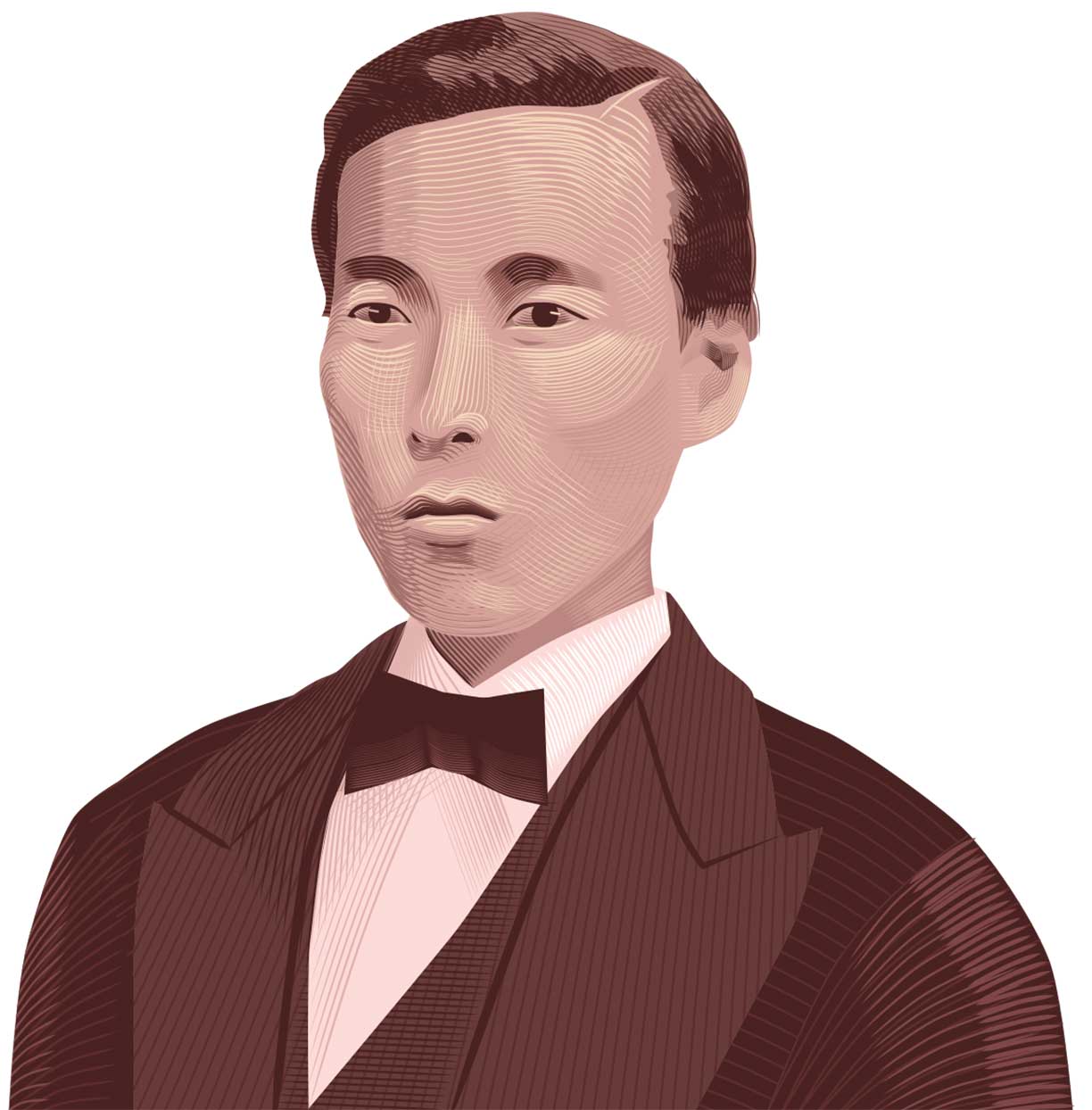

The first Japanese student to attend Princeton was also one of the last samurai. Hikoichi Orita 1876, a samurai by training, worked as a page for the lord of the Satsuma han, or feudal clan. After the Meiji Restoration of 1868, when the shogunate ceded its power and the Japanese imperial family reassumed rule, the samurai caste faded away.

In 1870, Lord Iwakura Tomomi, who was embarking on a diplomatic mission to the United States and Europe, decided to send his two sons to complete their educations at Rutgers University. Orita agreed to go along as an aide. A missionary from New Jersey talked Orita into enrolling at Princeton, where he could pursue his own Western education while keeping tabs on the lordlings.

Orita chronicled his experiences at Princeton in a diary that he wrote in almost daily from January 1872 to December 1876. The diary, which tracks his expenses, activities, and occasional reflections, offers a keyhole glimpse into the life of an early international student who found the University a place of little comforts and big ideas — and went on to grow a university of his own.

A natty dresser, he bought new neckties frequently and spent about $600 in today’s money on “a nice overcoat.” He also bought a “study gown,” a loose, belted garment of the period — made of silk or flannel, with perhaps a fur collar — meant to keep the wearer infinitely comfortable during long hours of ink-stained drudgery while looking infinitely elegant.

His other purchases were modest: licorice (a frequent item); soap; toothbrushes and “tooth powder”; matches, oil, and oilcloths for his lamps; stamps and envelopes for letters to his friends. He paid $15 (about $390 today) to Whig Hall, presumably as a membership fee.

His real weakness was books. In a single year, he spent more than $2,200 in today’s money on books, including The Living Lincoln, Three Centuries of Modern History, A Manual of Ancient History, Xenophon’s Anabasis, Euclid, Cicero, Horace, Homer, Plato, Virgil, the Greek New Testament, and the “Commoner Bible.” For pleasure reading, he bought Robinson Crusoe, a story of another man who kept a diary to record his life on a distant shore.

“He worked like a Trojan,” wrote Marius Jansen ’44, a professor of East Asian studies at Princeton. “He writes of ‘recitations’ in Greek, Latin, French, and German. He took classes in history, logic, rhetoric, psychology, physics, mathematics, anatomy, and physiology, as well as private singing lessons.”

Orita corresponded constantly with friends back home, visiting the post office almost daily. His world was changing in his absence. In 1873, he wrote that Japan had switched from the lunar calendar to the Gregorian calendar: “I heard that our calendar was changed, as same as the Europeans.” His remarks on time’s passage are always a little sad. On Jan. 1, 1872, he wrote, “Early morning congratulated ‘Happy New Year’ with each other, as is the custom of this country. There is nothing more difference as another day.” On Jan. 1, 1875, he wrote, “Happy New Year! This is my fifth year in this land. Quietly but lonely I spent the day in my room.”

After taking his degree, Orita returned to Japan. He served for decades as the head of Third Higher School, which became Kyoto University; the university has a statue of “Professor Orita” on its grounds today, honoring him as one of its founders.

In designing his school’s student life and classroom culture, the historian Donald Roden argues, Orita kept Princeton in mind as a model of “how cohesive a group of students could be in their expression of loyalty to a school.” Naturally, he made a point of greatly enlarging the school’s curriculum in classic Japanese literature. You simply cannot have too many books.

Orita died in the influenza pandemic in 1920.

3 Responses

stevewolock

4 Years AgoFor the Record

The December “Princeton Portrait” story about Hikoichi Orita 1876 underestimated the value of his $15 Whig Hall membership, which would be about $390 in today’s dollars.

Campbell Gardett ’68

4 Years AgoArigatou!

What a terrific find! Thank you! Somebody send this right away to Steven Spielberg or Tom Hanks!

It would be interesting to have highlights of his diary and letters and later reflections. A lot of work, of course. Anyway, Arigatou, Elyse! You cannot have too many books or unexpected people!

Murphy Sewall ’64

4 Years AgoInflation and Education

I’m puzzled at the “today’s dollars” references in the interesting article about Hikoichi Orita 1876. For example, a $15 payment to Whig Hall is referred to as about $100 in today’s money. Online inflation calculators go back only as far a 1913, but $15 in 1913 would be $419.07 in today’s dollars. The value of a dollar in 1876 presumably was greater than that of a 1913 dollar. Something appears off in the currency adjustments.

A Princeton education certainly seems expensive today. For example, today’s tuition and fees compared to mine in the 1960s exceed the rate of general inflation by quite a bit. An article on the cost of attending Princeton over the years compared to CPI rates might be illuminating.

Editor’s note: Inflation calculators online appear to set the value of $15 in the 1870s at about $390 today. The story has been updated.