Two hundred and twenty years ago this month, Nassau Hall caught fire and burned to its skeleton. “In two hours from the time it was discovered on fire,” a newspaper reported at the time, “the whole building, walls excepted, was reduced to ashes.”

The administrators of Princeton College believed the fire was an act of arson. But more than this: They believed the disaster testified to the wickedness in which college students naturally live, of which this fire was only the outward manifestation. Right after the fire started, one student, George Strawbridge 1802, ran up to the belfry of Nassau Hall to throw water on the burning roof. He reached the top of the belfry at the same moment as Samuel Stanhope Smith, the president of the college. Smith saw the blaze, threw up his hands, and cried, “This is the progress of vice and irreligion!”

The administrators identified two students whose general conduct was (the argument went) unbecoming of a Princeton student and therefore suggested they were guilty of lighting the fire — both literally, with kindling, and metaphorically, with the flames of hellfire that licked their heels. (One of the students had a reputation as a “freethinker,” or religious nonconformist.) The College suspended the two students on the charge of arson.

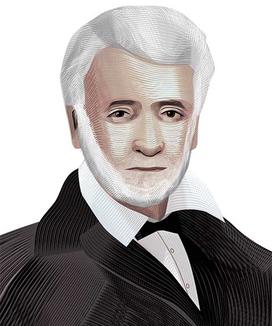

Strawbridge, who hailed from Maryland, decided to investigate the fire himself. He had good reason to doubt the official story, as he was one of the few people to see the fire up close when it started.

The administrators identified two students whose general conduct was (the argument went) unbecoming of a Princeton student and therefore suggested they were guilty of lighting the fire — both literally, with kindling, and metaphorically, with the flames of hellfire that licked their heels.

Late in his life, he recorded his deductions in an unpublished memoir, now in the University’s Mudd Archive. On the day of the event, he had arrived for lunch in the college dining room when voices outside shouted, “Fire!” Running to join the commotion, he saw people pointing at the roof of the building. His room in Nassau Hall happened to be next door to the top of the belfry, which was the only way onto the roof. “I ran back to my room,” he wrote, “brought the pitcher and basin, and threw what was in them on or at the fire.” Heroic, but too late.

When the College accused students of wrongdoing, “I made it my affair, young as I was,” Strawbridge wrote, “to acquaint myself with the facts.” For a start, this was a locked-door mystery: The fire started, some said, in the belfry, but the belfry door was always locked. (The servant with a key opened the door to fight the fire after it started.) Another puzzle: the instrument of the crime. “The invention of Locofoco matches was then unknown and people carried the kindling for their fires most commonly in shovels,” he wrote. Could one plausibly imagine a culprit carrying a fire on a shovel through the crowded halls of the school in order to dump it in the belfry?

And what of the motive? The fire couldn’t have disguised theft, for — despite their abiding wickedness — the students lived simply, Strawbridge wrote: “The hand that did it ran a most fearful risk of detection, and for what object?”

“It could have come in but one other way,” Strawbridge concluded: a chimney fire. Indeed, rumor had it that one of Nassau Hall’s chimneys had briefly ignited that very morning. The locked-door mystery had its solution in its initial clue: The door was locked, and no crime occurred.

Strawbridge didn’t get the chance to testify on behalf of the accused students, but he helped to turn public opinion away from the conviction that the fire was arson. The College eventually found them innocent and lifted their suspension, although one, the freethinker, declined to return.

Strawbridge became a lawyer and later a judge on the Louisiana Supreme Court. Like other Southern alumni of his generation, Strawbridge broke with Princeton after it affirmed its support for abolitionism in the years leading up to the Civil War.

1 Response

btomlins

3 Years AgoFor the Record

The Princeton Portrait about George Strawbridge 1802 (March issue) mischaracterized the timing of his break with Princeton, which came after the College affirmed its support for abolitionism in the years leading up to the Civil War.

In a passage from his memoir, Strawbridge noted that a large number of Princeton graduates were from the South. “One effect of the spirit of abolitionism has been to destroy this connection in a considerable degree, probably altogether,” he wrote. “I scarcely think my name will appear there in another generation, although I still cherish a love for these old institutions, especially the Whig society.”