Princeton Portrait: They Wrote the First (Not-So-Great) American Novel

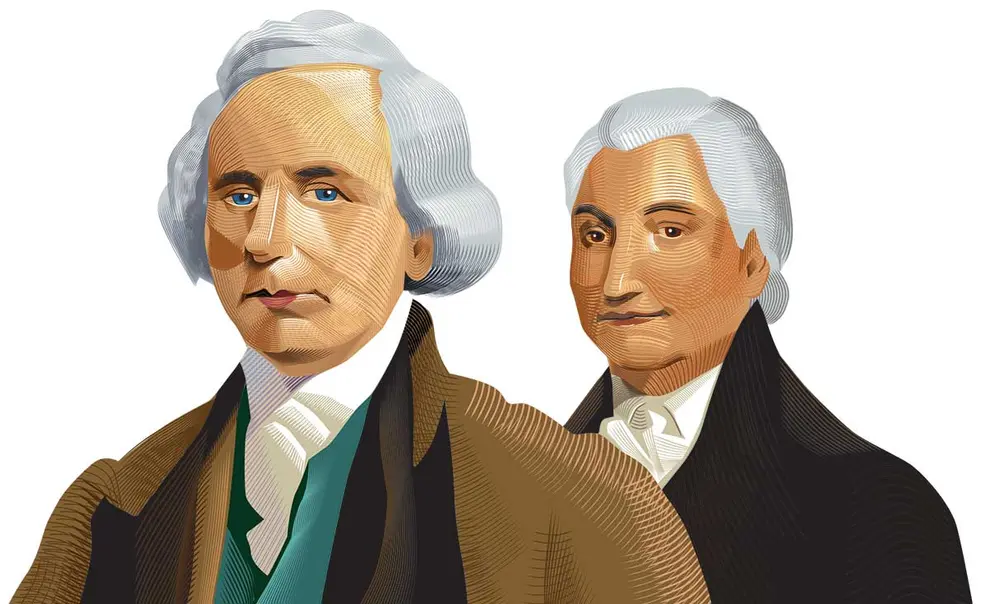

Hugh Henry Brackenridge 1771 (1748-1816) and Philip Freneau 1771 (1752-1832)

The first American novel was also the first Princeton campus novel. Hey, always start on your best foot.

In 1770, Hugh Henry Brackenridge 1771 and Philip Freneau 1771 wrote Father Bombo’s Pilgrimage to Mecca in Arabia, which holds as good a claim as any to the title of oldest American novel. (The closest rival to the claim, Francis Hopkinson’s A Pretty Story, was published in 1774.)

The two young men collaborated on the novel as undergraduates at the College of New Jersey. Brackenridge, a farm boy from Pennsylvania, and Freneau, a toff from New Jersey, were among the founders of the Whig Society. (James Madison 1771, a friend of theirs, was another founder.) The Whigs were a belletristic lot; Madison later said his classmates spent their college years growing “nothing but flowers in their gardens” and forgetting that gardens can also grow food. Brackenridge practiced oratory; Freneau wrote dramatic, furiously ornamented poetry, taking an obvious interest in the passages of Shakespeare, like Macbeth’s “sound and fury” speech, that (to echo Frank McCourt) aren’t calls to arms, but sound like calls to arms.

In their junior year, Whig and Clio started a “paper war,” firing vicious satires back and forth at each other. Father Bombo’s Pilgrimage emerged from this war. A satirical travelogue in the mold of Gulliver’s Travels, the novel makes fun of Princetonians — Cliosophians especially — while pretending to make fun of Americans broadly.

The novel gestures at fantasies of the “exotic” Middle East, reflecting a contemporary vogue for The Arabian Nights. But a reader might well describe it as a campus novel, since the characters are based on fellow students and the plot is based on events that took place during the authors’ time in college. The plot begins when a young man named Reynardine Bombo, a student at an “antique and famous castle” — which a footnote in the original manuscript glosses as “New Jersey college” — sets out on a journey to Mecca because the Prophet Mohammed appears to him in a dream and bids him do so in penance for “the crime of Plagiarism.” (Bombo seems to be based on a classmate named, marvelously, Samuel Eusebius McCorkle 1772.)

“Bombo may be based, strictly speaking, on the supposed foibles of Princeton undergraduates; But one finds in him, as well, fascinating hints of such later American anti-heroes as Ichabod Crane, Simon Suggs, or even Huckleberry Finn.”

Perhaps mercifully, the novel’s citation of the Middle East doesn’t go much further than giving some characters pseudo-Arabian names and giving the protagonist a turban. Bombo’s travels take him through taverns (he mixes together brandy, cider, mead, and rum to produce the kind of unholy brew that, in my day, we called “swamp water”), brothels (he mistakes one for an inn), barbershops (after a long debate that parodies Cliosophic sophistry, he chooses a color for his wig), and King’s College (today, Columbia University; he crashes in a friend’s room, but the friend moves him while he sleeps, as a prank, and he wakes up in a field).

In short, a college student: fratty, bookish, juvenile, vain about his dress. And given to procrastination. Bombo spends almost the whole novel braving the fantastic perils of New Jersey and New York before he makes a final, rushed trip in and out of Mecca.

At their Commencement, Brackenridge and Freneau read aloud a poem they co-authored, “The Rising Glory of America.” Afterward, Freneau became a poet, earning the nickname “the Poet of the Revolution” for his anti-British satires. Brackenridge founded the Pittsburgh Gazette and wrote another satirical novel, Modern Chivalry. He became a judge on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

Writing in 1975 for Princeton Alumni Weekly, Michael Bell argued that Father Bombo’s Pilgrimage really did forecast the future of the American novel: “Bombo may be based, strictly speaking, on the supposed foibles of Princeton undergraduates; his adventures may burlesque the vogue of the Oriental Tale, and he may occasionally recall such earlier literary figures as Don Quixote or Fielding’s Parson Adams. But one finds in him, as well, fascinating hints of such later American anti-heroes as Ichabod Crane, Simon Suggs, or even Huckleberry Finn.”

1 Response

Wayne S. Moss ’74

3 Years AgoBrackenridge and Freneau’s Prophetic Commencement Address

I appreciate Elyse Graham ’07’s portraits of James Madison 1771’s classmates Hugh Henry Brackenridge and Philip Freneau (Princeton Portrait, October issue).

I’d just like to add that Brackenridge, Freneau, and Madison grew up in a culture of white American Protestantism, which was very much entrenched in colonial Princeton. From this perspective, Brackenridge and Freneau lampooned the Cliosophs by making Bombo a Catholic and his pilgrimage eastward to Mecca of all places. I suspect that Brackenridge and Freneau had a blast mocking the Cliosophs as outside the protestant America mainstream and Bombo as a fool for thinking he could find solace and redemption in the Muslim Middle East. By our standards, this humor is egregious, but Brackenridge and Freneau are not writing for us — they are writing within the accepted standards of protestant colonial America and particularly their small American Whig Society of 1770.

Now let’s consider “The Rising Glory of America.” This was the 1771 student Commencement address read by salutatorian Brackenridge. Unlike Father Bombo, which looks east, “Rising Glory” looks west and is prophetic. It sees a great civilization which will stretch from coast to coast. It sees America preparing for its role as the new thousand-year center of global commerce, culture, literature, and the arts, replacing ancient Greece, Rome, and England, each of which had their day in the sun. As American historian Joseph Ellis points out in After the Revolution, “Rising Glory” fits within the idea of translatio studii or translatio imperii, “that civilization, like the sun, moved from east to west and that the North American continent was therefore destined to become the habitat for the arts and sciences at some unspecified time in the future.” Brackenridge and Freneau even predicted that the New Jerusalem would land in America, notably in New Jersey.

While these ideas may seem naive and outdated to the modern Princeton community, I would suggest that the notion of American cultural supremacy persisted in one way or another for at least our nation’s first 200 years, certainly up until the nation’s bicentennial in 1976. Many would argue that it continues today, particularly in the context of American exceptionalism, our attachment and dependence on the U.S. Constitution for the protection of freedom, and America’s persistent leadership in the sciences and engineering.

Finally, despite its chauvinism, there is a vision and spirit underlying “Rising Glory.” One can hope that Princetonians everywhere will take ownership of that vision and spirit and help make the promise of America available to all Americans and, in the words of our informal motto, all humanity.