Princeton's Farewell to President Woodrow Wilson ’79

Under the auspices of the Woodrow Wilson Club of the Borough of Princeton, on the evening of March 1st, the Saturday preceding his departure for Washington, the people of the town joined with the students of the University in formally saying goodbye to President Wilson, and wishing him godspeed upon leaving his home town to assume the presidency of the nation. The demonstration was entirely non-partisan, the citizens generally joining in expressing their farewell and good wishes to their distinguished fellow-towns-man.

A handsome silver loving cup standing eighteen inches high and weighing eighty-nine ounces was presented to the new President. It is inscribed: “Presented to Woodrow Wilson, President of the United States, by the citizens of Princeton, fourth March, 1913. The reverse side bears the seal of the Borough of Princeton.

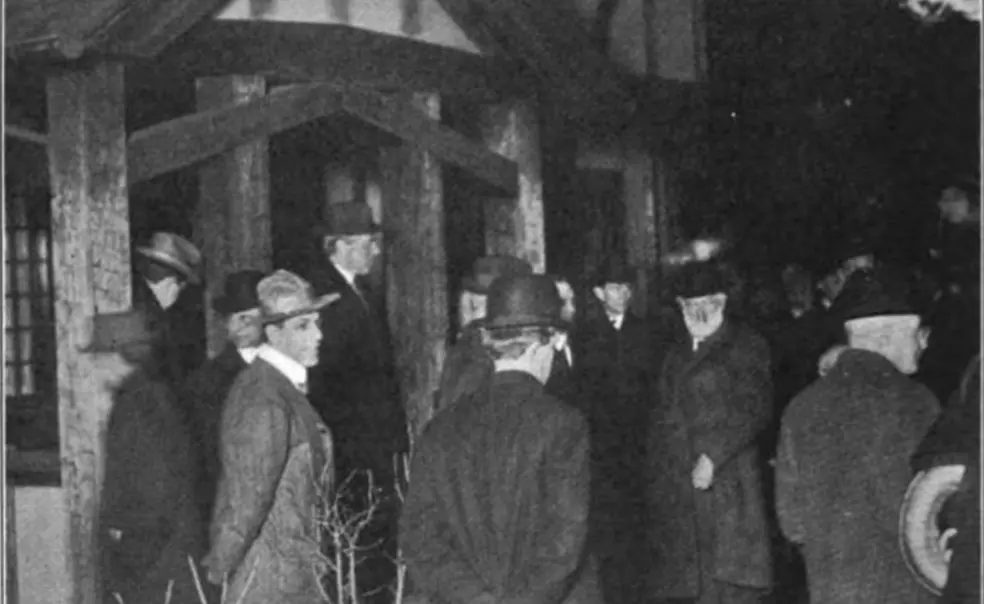

A crowd of about 3000, carrying Japanese lanterns and headed by a band, President Joseph S. Hoff of the Woodrow Wilson Club, Mayor Alexander H. Phillips ’87, and an honorary committee of citizens, paraded from Nassau Street to the President’s home on Cleveland Lane. Responding to the cheers of the crowd, the President appeared at his front door, whereupon Messrs. Charles S. Robinson, postmaster of Princeton, and Albert S. Leigh, on behalf of the citizens, presented the loving cup. Colonel David M. Flynn, cashier of the First National Bank of Princeton, made the speech of presentation, in which he expressed the pride of the community in the election of one of its members to the presidency, and said in conclusion:

“We have only loaned you to the nation, and when the great work you have before you at Washington is accomplished, it is our earnest hope that you will come back to old Princeton and spend your days with us.”

In responding President Wilson said:

“Colonel Flynn and my fellow citizens: I feel very deeply complimented that you should have gathered here tonight to say a good-bye to me and to bid me godspeed. I have felt a very intimate identification with this town. I suppose that some of you think that there is a sort of disconnection between the university and the town; and perhaps some of you suppose that it is only since I became Governor of this state that I have been keenly aware of the impulses which have come out of the ranks of the citizens of this place to touch me and inspire me – but that is not true. I think you will bear me witness that I have had many friends in this town ever since I came here, and that one of the happiest experiences I have had day by day has been the grasp of the hand and the familiar salutation which I have met at every hand.

“I experienced only one mortification in this town: I went into a shop one day after I became President of the University and purchased a small article and said, ‘Won’t you be kind enough to send that up?’ I had purchased it of a man with whose face I had been familiar for years, and he said, ‘What is your name, Sir?’ That was my single mortification, and that is the keenest kind of mortification; because if there is one thing a man loves better than another it is being known by his fellow-citizens.”

“Now, my friends, I said the other day, and I said it most unaffectedly, that I was going keenly to enjoy these three days as I was, and I admit Colonel Flynn used very appropriate words. I am both a plain and an untitled citizen. I have admitted my plainness many times. I said that I was going to enjoy these three days and I am enjoying them. Not because they ae days when I am not particularly responsible for anything, but because they are days that remind me of the many years I have spent in this place, going in and out as one of your own number; and I want you to believe me when I say that I shall never lose that consciousness. I would be a very poor President if I did lose it. I have always believed that the real rootages of patriotism were local, that they resided in one’s consciousness of an intimate touch with persons who were watching him with a knowledge of his character.

“You cannot love a country abstractly; you have got to love it concretely. You have got to know people in order to love them. You have got to feel as they do in order to have sympathy with them. And any man would be a very poor public servant who did not regard himself as a part of the public. No man can imagine how other people are thinking. He can know only by what is going on in his own head, and if that head is not connected by every thread of suggestion with the heads of people about him, he cannot think as they think.

“I am turning away from this place in body but not in spirit, and I am doing it with genuine sadness. The real trials of life are the connections you break, and when a man has lived in one place as long as I have lived in Princeton and had as many experiences as I have had here, first as an undergraduate and then as a resident, he knows what it means to change his residence and to go into strange environments and surroundings. I have never been inside of the White House, and I shall feel very strange when I get inside of it. I shall think of this little house behind me and remember how much. More familiar it is to me than that is likely to be, and how much more intimate a sense of possession there must be in the one case than in the other. One cannot be neighbors to the whole United States. I shall miss my neighbors. I shall miss the daily contact with the men I know and by whom I am known, and one of the happiest things in my thought will be that your good wishes go with me. I shall always look at this beautiful cup with the greatest pleasure, because it reminds me of this occasion and of all that you have meant to me.

“You have said very kind things about me, but no kinder than I could say about you. With your confidence and the confidence of men like you, the task that lies before me will be gracious and agreeable. It will be a thing to be proud of, because I am trying to represent those who have so graciously trusted me.”

The crowd then passed in front of the porch and shook hands with the future President. The town’s good-bye to the President-elect was brought to an appropriate close with the singing of “America,” “Auld Lang Syne,” and “Old Nassau.”

This was originally published in the March 5, 1913 issue of PAW.

No responses yet