In 1994, when Paramount advertised an open casting call in Princeton for its upcoming film I.Q. — a romantic comedy featuring Albert Einstein, his fictional niece, and the niece’s lovestruck suitor — the response was extraordinary. Some 10,000 people showed up, beginning a town-gown bout of “ I.Q. fever” that would last until filming wrapped in July. Locals flocked to catch a glimpse of stars Walter Matthau, Meg Ryan, and Tim Robbins on sets that ranged from a gas station in nearby Hopewell to a temporary bandshell built on Cannon Green. As Caroline Moseley reported in PAW, an assistant university archivist, Nanci A. Young, provided photos of Einstein’s Princeton to help Nora A. Olgyay ’74, the coordinator of the film’s art department, ensure authentic sets and costumes. That attention to detail would earn strong marks from New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin, who called I.Q. “a visual pleasure.”

Below, read Moseley’s PAW feature about the memorable summer when Hollywood came to campus.

Einstein: The Movie

By Caroline Moseley

(From the Sept. 14, 1994, issue of PAW)

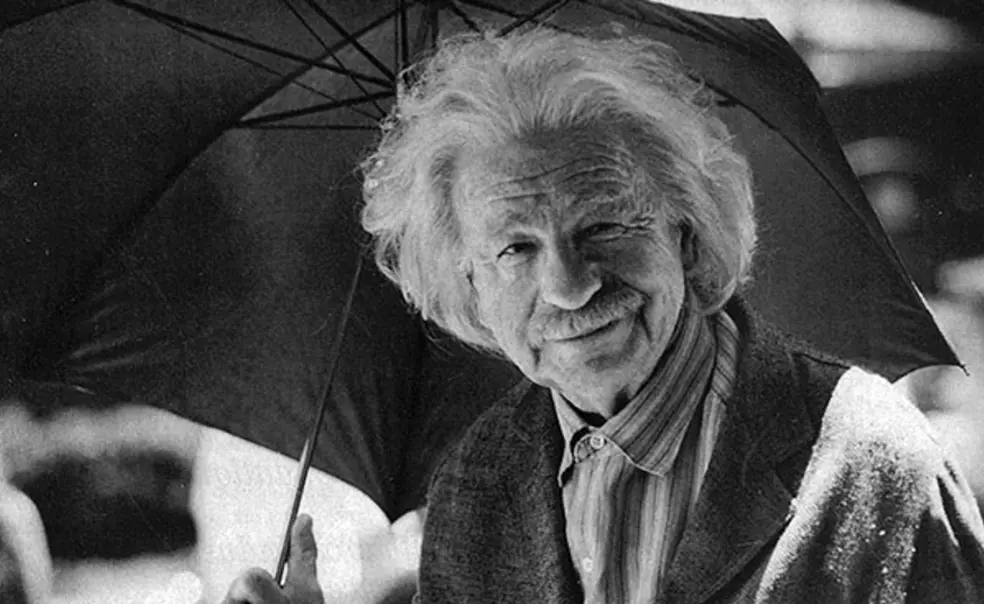

Coming this year to a theater near you: I.Q., a romantic comedy filmed in and around Princeton this spring and summer. The plot? Boy meets girl. Boy is local auto mechanic, girl is Albert Einstein’s niece, and Einstein is resident Cupid. I.Q. stars Tim Robbins (The Player) as the mechanic, Meg Ryan (Sleepless in Seattle) as the fictional niece, and Walter Matthau (Dennis the Menace) as Einstein. The film, set in the early 1950s, is directed by Fred Schepisi (Six Degrees of Separation). I.Q. is scheduled to open December 9th.

Paramount Pictures, the studio producing I.Q., first contacted the university in August 1993, says Justin Harmon ’78, the director of communications, “to describe the project and state their interest in shooting some scenes on the campus.” Though Harmon’s office receives frequent requests to shoot commercials on the campus, he says the request to shoot a feature film is “a rarity. We decided to engage the project with a sense of adventure, good humor, and the expectation that we’d be able to help the producers make a better movie — which, we hope, has been the case.” The university’s decision was based in part, notes Harmon, on the advice of Broadway producer and former Princeton trustee Roger S. Berlind ’52, a colleague of I.Q.’s executive producer, Scott Rudin (The Firm).

Princeton requested “modest changes in the script,” says Harmon, to ensure that no actual Princeton professors were characters. The script makes it clear that Einstein, a faculty member at the nearby but unaffiliated Institute for Advanced Study from 1932 until his death, in 1955, was not a member of Princeton’s faculty. However, adds Harmon, “Paramount wanted to use the campus to establish the scene, to locate the movie historically and geographically.” The university was paid an undisclosed amount to cover expenses incurred by additional demands on its services, which included security and the use of grounds and buildings.

(Although he was never a member of the Princeton faculty, Einstein occupied an office in the university’s original Fine Hall — since renamed Jones Hallfrom 1933 until the completion of the Institute’s Fuld Hall, in 1939.)

Thus I.Q. fever struck Princeton, town and gown. In March, Paramount’s casting director issued a call in the local press for “upscale, preppy people” between the ages of eighteen and seventy-five. Some ten thousand people, including many professional actors, turned up at Princeton High School to audition; about a thousand made the cut.

Among the extras hired without auditions were Associate Professor of Chemistry Clarence E. Schutt and Research Physicist Robert Budny, who works at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

The finger of fame pointed at Schutt when I.Q. was filming near his home. In Schutt’s driveway sat his prized 1953 Buick Special, the ivory-andgreen behemoth he uses on weekends. “They spotted the car, asked if they could use it in the movie — and would I turn up at 6:30 a.m. the next day to drive it,” he recalls. There are approximately 150 vintage cars in the movie, says Schutt, most of which were supplied to Paramount by Picture Cars, of Brooklyn, New York, whose slogan is “Make Your Car a Star.” Schutt was an extra for three days, appearing as a motorist, “a passenger in a 1953 Packard, and a gardener in the background of a scene in which my Buick has a near-miss with Einstein’s De Soto.”

Budny, on his way to the bank, was asked by a Paramount staffer if he would consider being an extra. “I guess I looked the part,” says Budny, who appears in an audience of scientists at a physics symposium. Moviegoers will see Budny “in the second row of the auditorium, right behind Walter Matthau and four rows in front of Meg Ryan — unless I end up on the cutting-room floor.”

From the time it was announced, I.Q. provided endless copy, much of it speculative, for area newspapers. Who would be in the movie? Who could possibly play Einstein? Was it, indeed, proper to make a physicist of Einstein’s stature into a character in a Hollywood film? A typically gloomy headline read, “Those who knew Einstein fear filmdom’s distortions.” Some people reacted to the selection of Matthau for the lead role: Too tall? Too funny? Real-estate agents wanted to know if the stars would rent locally or commute from more exotic places, while others wondered if the movie would bring money and jobs to the area. (The film’s budget was reported to be $25 million, a figure that Paramount officials declined to confirm. Joseph Friedman, the executive director of the New Jersey Motion Picture and Television Commission, called I.Q. the state’s biggest Hollywood production ever, and he estimated that the film would pump more than $5 million into the local economy.)

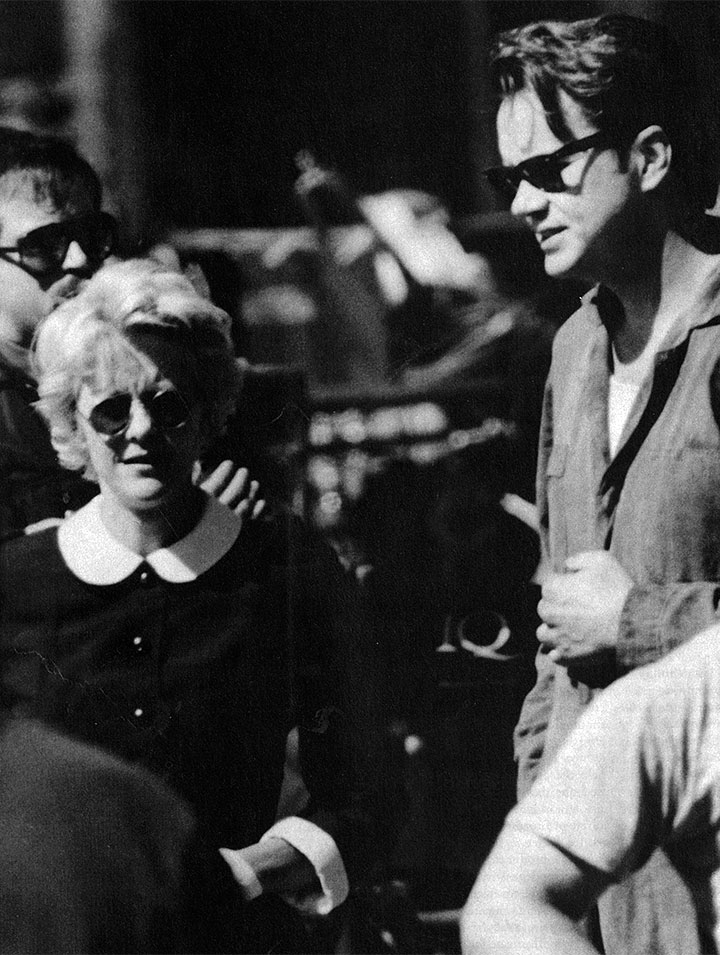

Once shooting started, the star sightings began: Walter Matthau had a drink at the Alchemist and Barrister, on Witherspoon Street — quite a few drinks, if all accounts were to be believed. Meg Ryan bought a turkey-on-rye sandwich at the Varsity Deli; well, actually, someone bought it for her, but that’s what she ordered.

There were also sightings manqués: Meg Ryan and husband Dennis Quaid were living quietly no one knew where, but the implication was that, with luck and frequent supermarket stops, you might run into them.

All shoots were thoroughly chronicled. Local extras were interviewed, as were merchants and passers-by who managed to exchange greetings or even smiles with the stars. Matthau was universally deemed the most accessible of the visiting luminaries.

The community witnessed a resurgence of popular interest in Einstein, who had suddenly become Princeton’s hottest property. Displays of Einstein memorabilia appeared in store windows along Nassau Street, and admirers of the great physicist began a campaign to erect a life-size bronze statue of him.

Large numbers of spectators, on foot and in cars, gathered wherever cameras rolled. Parking became even more difficult, though Paramount paid the Borough and Township for extra traffic control and the occasional street closing. Celebrity-seekers cruised Princeton and environs looking for the giant prop truck that marked the day’s filming.

In town, film locations included Palmer Square (refurbished with 1950s goods in shop windows), Bank Street, the Princeton Battlefield, the Institute for Advanced Study, and Mercer Street, the site of Einstein’s former home. The real Einstein lived at 112 Mercer Street, but 108 Mercer substitutes in the film. The company also went on location in nearby Lawrenceville and in Hopewell, where Andy’s Tire and Service Center was transformed into Bob and Al’s Automotive, a 1955 Mobil station complete with neon Pegasus (that’s where mechanic Ed works). A local motel served as the film’s administrative headquarters.

Campus locations, says Eric M. Hamblin, assistant director of visitor and conference services and the university’s liaison to the production, included Palmer Hall, Guyot Hall, Alexander Hall, Cannon Green, Elm Drive, and Carnegie Lake. Scenes were also filmed in the library of Cottage Club.

“Paramount came on an initial scout last Thanksgiving,” says Hamblin. “We walked around campus for four or five hours. They wanted rooms basically unchanged since the 1950s that were used for teaching science.” To ensure authenticity, Nanci A. Young, an assistant university archivist, provided Nora A. Olgyay ’74, the coordinator of the I.Q. art department, with 1950s-era photographs of campus exteriors and interiors. She also furnished period photos of students and faculty, so the actors would have appropriately short and Brylcreemed hair, narrow ties, khakis, and other sartorial markers of the period.

After rooms were selected, crew members accompanied Hamblin on a “technical scout” to identify aspects of given sites that needed changing. In Guyot 10, he says, “they replaced one door with a glass-paneled door to match the rear door, removed one row of seats, sanded the floor, then stained and ‘distressed’ it so it wouldn’t look newly finished. They also changed the exit signs.”

One of the more picturesque features of the I.Q. campus was an imposing bandstand erected on Cannon Green. “Some people suggested we keep it and use it for summer concerts,” says Hamblin, “but it was built as a prop, not as a real bandstand, and was showing wear and tear after a couple of rainstorms.” The bandstand, like everything built by the I.Q. crew, was dismantled and removed by its builders.

I.Q. accommodated Princeton’s academic schedule, with crews working during reading and exam periods, vacating the campus for Reunions and Commencement, and returning in mid-June, in time to “wrap” in early July.

For its part, the estivating campus accommodated the I.Q. entourage with surprising grace. The stars’ trailers, the makeup trailer, and the automobiles that drove the actors to location were parked in the lot behind the Lewis Thomas Laboratory, on the south end of the campus. On any given day, the campus might swarm with five hundred extras and up to one hundred crew members to handle cameras, sound, lights, costumes, makeup, and the all-important commissary (known as “Meals on Reels”). Because filming demands high-wattage lamps that make interiors extremely hot, Paramount supplied its own power and air conditioning, which were provided by two huge trailers that accompanied every shoot. “You can’t have actors sweating unless the script calls for them to sweat,” noted set dresser Byron Lovelace during a shoot in Richardson Auditorium.

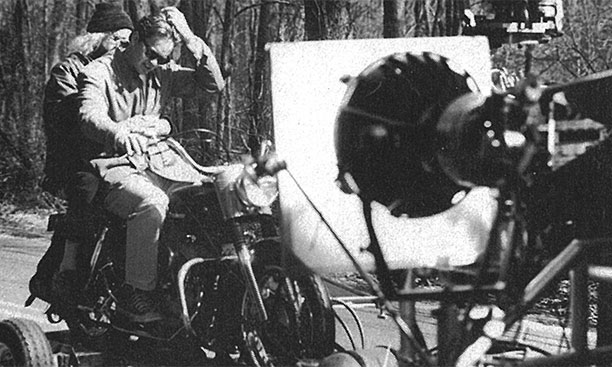

Interior shoots were closed to spectators, but the campus community turned out in force to watch outdoor scenes — and watch and watch and watch, because movie-making turns out to be a laborious business. One day in early May, “Einstein” and three Institute colleagues sat on Elm Drive in his De Soto, getting in and out of the car in take after take. After each slam of the car door, Matthau’s fluff of white hair was again coifed a la Einstein, his makeup patted and blotted, and his rumpled clothing rearranged into other rumples. Making movies began to look a lot like work. Said Norman McNatt, a spokesman for the Institute, “Considering that this is a place that prides itself on minimizing distractions, the filming attracted a lot of attention the first few days. But pretty soon we discovered that watching nine takes of the same scene is tedious,” even when the scene is “Einstein” roaring up to the Institute on a motorcycle.

When the Paramount crew pulled out of Princeton, it left not so much as a candy wrapper behind. Town and gown, agreeing that the movie folk had been very cooperative, promptly sank into the summer doldrums. No more crew members darting around with cellular phones, no more traffic jams on Mercer Street, no more chances to see Meg Ryan. All of a sudden, there wasn’t that much to talk about.

Still, fledgling movie actor Robert Budny had comforting words for Princetonians who remain fearful that, in I.Q., “St. Einstein might be desecrated. The movie is a comedy with almost no basis in fact-it’s very lighthearted. It’s just fun. Einstein’s scientific reputation is not in danger.”

No responses yet