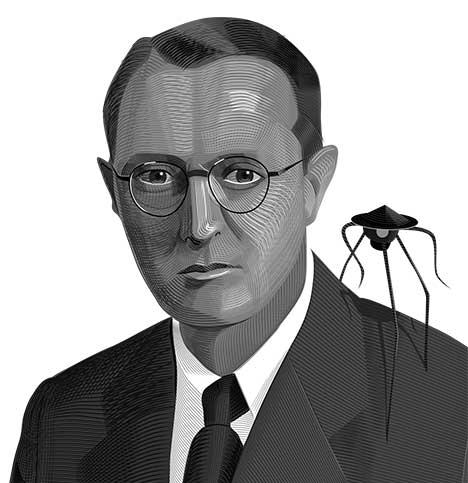

Professor Hadley Cantril Studied Hysteria After ‘War of the Worlds’

Princeton Portrait: A. Hadley Cantril (1906-1969)

When the Martians landed, they landed, as one might expect, in the center of the world: Princeton, New Jersey. Actually, they landed a few miles outside of town — in Grovers Mill, by Princeton Junction — no doubt fearing the destructive power of 2,500 University students ready to seize on any distraction from their studies.

A Princeton professor was on hand to see the event and sound the alarm: Richard Pierson, of the University’s observatory. On the fateful night, Professor Pierson was talking about astronomy with a reporter live on the radio when news of “a huge flaming object, believed to be a meteorite,” prompted the pair to change plans and drive to Grovers Mill, staying in contact with their radio audience. There, they saw a crater with a huge metal cylinder at the center.

“I don’t know what to think,” said Pierson. “The metal casing is definitely extraterrestrial — not found on this earth.”

A moment later, shadowy beings emerged from the cylinder and started firing weapons, engulfing a nearby crowd of humans in flames.

Thus began the infamous radio broadcast War of the Worlds, which, for a few hours on Oct. 30, 1938, convinced at least a million Americans that Earth was under attack by Martians. Frightened listeners wept, prayed, jammed emergency phone lines, and ran from their homes, carrying towels to protect themselves from weaponized extraterrestrial gas. A man ran into the office of the Princeton University Press Club “with the news that he had seen the rocket and the invaders piling out of it, each armed with a death ray.” Only later did listeners learn that the “invasion” was a radio play and that Professor Pierson was a fictional character.

A real Princeton professor named Hadley Cantril, a psychologist who specialized in radio propaganda, found himself ideally situated to analyze the inadvertent hoax. In 1940, he published a book, titled The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic, that is still pertinent in our age of misinformation. Cantril found that listeners were more likely to figure out the invasion was a fiction if they checked the information against sources that were not affected by the broadcast — for instance, if they turned the radio dial instead of calling friends or running outside to consult neighbors. Education was helpful — an 11-year-old girl stayed calm because she knew the work of H.G. Wells, whose 1898 novel, War of the Worlds, inspired the broadcast. Cantril found that a fantastical story will seem believable if it comes from a person who appears trustworthy. (One listener reported, “I believed the broadcast as soon as I heard the professor from Princeton and the officials in Washington.”)

A shrewd, sociable son of Utah, Cantril ran the University’s Office of Public Opinion Research and advised three presidents — Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, and John F. Kennedy — on psychology and public affairs. In his book, he warned that feeling helpless can tip people from doubt into hysteria: “The coming of the Martians did not present a situation where the individual could preserve one value if he sacrificed another. It was not a matter of saving one’s country by giving one’s life or helping to usher in a new religion by self-denial, or risking a bullet to save the family silver. … Nothing could be done to save any of them. Panic was inescapable.”

Princeton students reveled in their close call with the otherworldly. After the broadcast, The Daily Princetonian published a doctored photograph that showed a huge Martian tearing apart Cleveland Tower. Students formed the League for Interplanetary Defense, which aimed, tongue-in-cheek, to prepare campus for a real invasion. The league distributed leaflets listing useful precautions (“Have all doors and windows meteor-proofed”), together with a warning: “What happened at Grovers Mill may happen in stark reality in the near future, the cry of ‘wolf’ may turn to fact! Death and destruction lurk in the heavens!”

1 Response

Robert D. Bolgard ’57

3 Years AgoInfluential Professors in the 1950s

I was glad to see the article about Professor Hadley Cantril (Princeton Portrait, October issue). Although I majored in history, partly because of its all-star cast of professors (Black, Cantor, Craig, Harrison, Lee, Palmer, and Strayer come to mind), I also tried to take courses with prominent professors like Martin and Stohlman in art, Baker and Thorpe in English, Kaufman in philosophy, Mason in politics, Ramsey in religion, Tumin in sociology, Armstrong and Fine in classics, and others. It was thus an easy choice to enroll in Dr. Cantril’s course in “Social Psychology.” Although the Martian invasion broadcast was an interesting part of the course, I believe that Cantril’s greatest contribution was his magnum opus, The ‘Why’ of Man’s Experience. His teaching about human motivations has enabled me and countless others to understand and appreciate greatly our fellow beings.