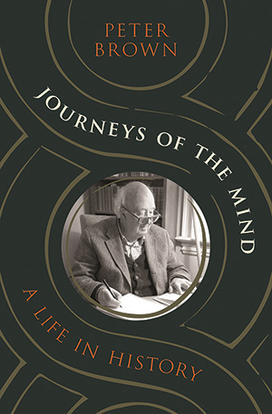

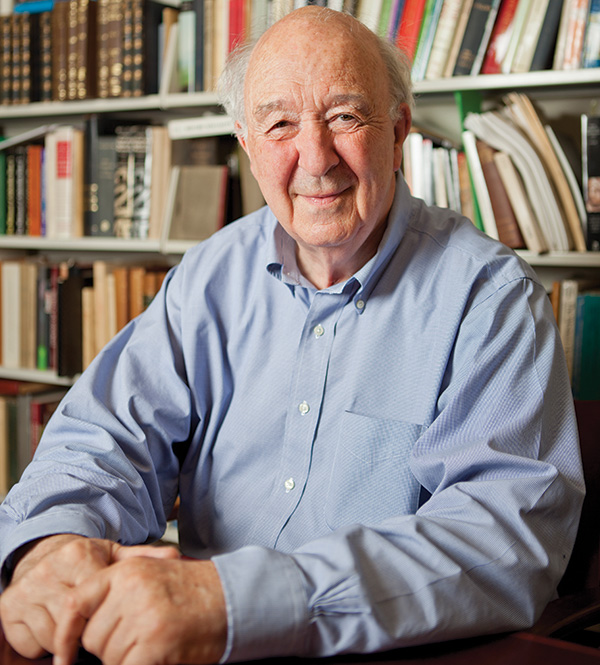

Professor Emeritus Peter Brown Wrote the Journey of His Mind

In an autobiography, Brown tells of his childhood in Dublin, studies at Oxford in the ’50, and more

“I had to explain myself by becoming a historian of myself,” professor emeritus Peter Brown writes in his new book Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History. Most famous for his biography of philosopher Augustine of Hippo — his first book — Brown went on to rewrite the history of the later Roman Empire and the centuries that followed its collapse in the prolific body of work that followed.

“There was a view that later Roman history was a period of decline,” says Jack Tannous *10, an associate professor of history at Princeton who studied under Brown. “Peter approached that period, which he called late antiquity, as a time of exciting transformation. He rehabilitated a period that had been seen as a backwater.”

In Journeys of the Mind (Princeton University Press), Brown, a professor of history at Princeton from 1986 until his retirement in 2011, traces the intersection of his own life, the development of the academic field he helped create, and the scholars he met. “Intellectual products come out of very specific environments,” Brown tells PAW.

He first thought about writing such a book when he came to the U.S. to teach in the 1970s but embarked upon the project only after he retired. Inspired by his favorite novelist, 19th-century English writer Anthony Trollope, Brown offers a portrait of an era and its personalities.

Brown vividly depicts the academic settings in which he worked. As a student at Oxford in the 1950s, he hears the American evangelist Billy Graham preach and the Christian thinker C.S. Lewis lecture on Milton. As a professor at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1970s, Brown discusses early Christian theology over beers at a campus bar with the French philosopher Michel Foucault. And at Princeton, Brown lectures on the Vikings and the Visigoths in his course History 343, which greatly appealed to “the young of the athletic persuasion — the jocks,” he writes.

Brown also writes about his childhood in Dublin and offers glimpses of his own religious development. His parents were Anglicans in a predominantly Catholic country, and, Brown writes, “I grew up in Ireland very aware that I was a member of a religious minority.” His childhood, he adds, left him “with complex memories that recalled many aspects (both positive and negative) of the last centuries of Rome.”

Being Irish would remain a central part of Brown’s identity, as he reveals when he describes arriving at JFK Airport in New York, for an Aer Lingus flight to Dublin in 1980 to see his father for the last time: “I saw my fellow countrymen gathered at the very end of the vast concourse — a gaggle of nuns, priests and gentlemen with brown hats, tweed jackets and rumpled woolen cardigans. I was home again.”

His Irish background also meant that Brown would always be something of an outsider at Oxford. In 1962, he embarked on the study of Augustine, a foundational Christian thinker and prolific writer. In reading The Confessions, Augustine’s spiritual autobiography, Brown writes, “I took into myself something of Augustine’s profound sense of the complexity of the self and of the hiatus between the depth of the inner world and the brittle surface of things. It seemed to resonate with my own disquiets in the world of Oxford.”

Published in 1967, the Augustine biography was immediately hailed as a classic, but Brown, aided by an extraordinary ability to learn new languages and synthesize disparate strands of scholarship, shifted his focus to the religious world of the Near East and the Middle East.

In April 1974, he traveled to Iran, a trip that was pivotal for him personally and professionally, and makes for one of the most compelling sections of Journeys of the Mind. “The countryside was covered with unpruned cherry trees in exquisite, full blossom with branches twisting like flames,” he writes.

Seeing “the landscapes and monuments of the Sasanian Empire,” which controlled Iran from A.D. 224 to 651, when the Muslims conquered it, “added a whole new dimension to my knowledge of the late antique world,” Brown writes.

He also had profound encounters with Islam, Armenian Christianity, and Zoroastrianism that made the trip “a journey of the heart.” On his return to England, he writes, “after a lapse of 20 years, I resumed regular attendance at a Christian church.”

Brown tells PAW that he wanted the book to have “an element of pastness,” and he concludes his narrative with the death of his mother in 1987. In a final coda, he discusses his time at Princeton, where he and his wife, Betsy, still live in a house close to campus. He wakes up early every morning “to say my prayers and to turn, before dawn’s early light, to reading ancient languages,” he writes, most recently Ge’ez (classical Ethiopic) so he can grapple with texts “that still echo at a vast distance of time and space the controversies and ascetic legends of Syria and Egypt of the fifth and sixth centuries.”

No responses yet