Professors Advocate Free —and Controversial — Speech in Academia

The Journal of Controversial Ideas provides a home for contentious scholarship

The abusive emails began arriving as soon as bioethicist Francesca Minerva’s scholarly article on the moral status of newborns went viral in early 2012. One stranger vowed to pry open her skull and set fire to it. Another claimed to live in Melbourne, Australia, where Minerva had recently begun a postdoctoral fellowship. “Watch your back,” the message warned.

For the next nine years, Minerva struggled to find a tenure-track job; the controversial article, she was told, had made her radioactive. Meanwhile, other academics also faced intimidation — sometimes from outsiders, like the abortion opponents who had threatened Minerva, and sometimes from fellow scholars circulating open letters demanding that journals withdraw controversial papers or that universities rescind hiring decisions.

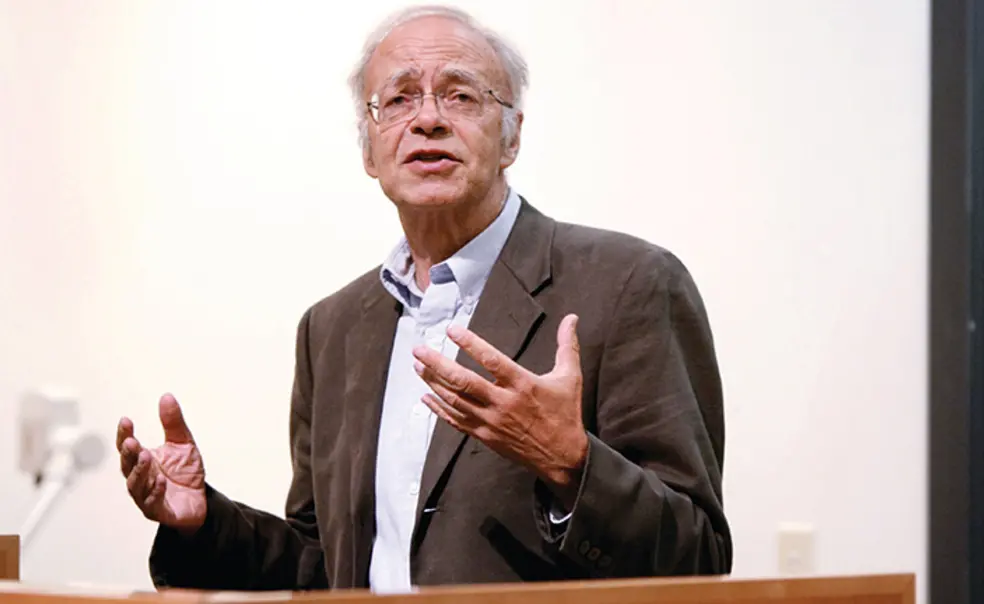

“There’s a climate in which people are prepared to attack academic work because they disagree with its political implications or with the politics behind it, where really in academic life we ought to be concerned with the standard of the arguments,” says Princeton philosopher Peter Singer.

In response, Minerva and Singer, along with the Oxford philosopher Jeff McMahan, launched the multidisciplinary, peer-reviewed Journal of Controversial Ideas (journalofcontroversialideas.org), a free, online scholarly publication that gives its contributors the option of publishing under pseudonyms, in order to avoid Twitter trolls and professional ostracism. The first issue, three of whose 10 articles are published pseudonymously, appeared in April. (To help young scholars who want to publish under pseudonyms, the editors will, upon request, confirm authorship to hiring and promotion committees.)

The journal’s founders insist their aim is not provocation for its own sake.

Although their editorial board comprises dozens of writers and scholars representing a range of academic disciplines and political opinions, the journal’s founders are currently covering most publication costs themselves while seeking tax-deductible donations to fund future issues.

When the idea for the journal first surfaced publicly in late 2018, it drew praise from those who believe that social-media mobs and left-wing political correctness are chilling the free exchange of ideas, especially around such hot-button topics as race, immigration, gender, and sexuality. But critics predicted that pseudonymous publication would provide cover for the mainstreaming of hate speech and encourage what they see as the false notion of an oppressive, politically monolithic academy.

“It’s playing right into the hands of the right,” says Aurelien Mondon, senior lecturer in politics at England’s University of Bath. “We have real problems in academia, but I don’t think the problem is that we can’t publish whatever we want.”

The journal’s founders insist their aim is not provocation for its own sake. Although their first issue touches on potentially incendiary matters — including transgender identity, violence in defense of animal rights, and the debate over genetic influences on intelligence — the articles “show that these issues can be discussed in a rational way, without accusations and without polemics and without denunciations of particular individuals,” McMahan says. “Our whole aim is to get people to discuss the ideas and not attack other people.”

Over the past two years, Singer says, more academics have begun pushing back against apparent efforts to enforce orthodoxy: Two dozen Princeton professors, including Singer, are among the members of a newly formed Academic Freedom Alliance dedicated to supporting embattled faculty everywhere.

Academics have faced threats before: When Princeton hired Singer 22 years ago, both he and then-University President Harold Shapiro *64 received death threats from people furious over Singer’s position on the morality of euthanizing disabled newborns. But the speed and reach of social media have worsened the problem; even the founders of the Journal of Controversial Ideas acknowledge that the perceived need for it is an unfortunate sign of the polarized times.

“We also think this is sad,” says Minerva, now a researcher in philosophy at the University of Milan. “We really hope this journal will be necessary for a very short time.”

1 Response

Mark Ramsay ’76

4 Years AgoThanks to the Courageous Scholars

Thank you, PAW, for writing about the Journal of Controversial Ideas (On the Campus, July/August issue). I am happy that a group of Princeton professors are advocating for dialectic argument that Peter Abelard and Saint Anselm practiced in the Middle Ages. These two philosophers helped motivate establishment of the first Western university, in Paris.

Our culture has been overrun with adhesive narratives of social maladies originating from specious causes. Nowhere in my reading of history has a culture that thought like this survived. We have to stop totalitarian thinking from exiling the Galileos of this world.