Q&A: Ashley Dawson on Climate Control

New climate-action plans help communities take charge of their own climate destinies

In 2017, the nonprofit Sustainable Princeton received a $100,000 grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to develop a climate-action plan, with the goal of reducing the town’s greenhouse-gas emissions. Similar plans are being created by municipalities and organizations across the country as part of an effort to address climate change at the local level. Ashley Dawson, the Currie C. and Thomas A. Barron Visiting Professor in the Environment and the Humanities, spoke with PAW about why local climate-action plans are important, and what towns and universities like Princeton can do to address the problems that result from climate change.

What is a climate-action plan?

A climate-action plan is, at its most basic level, a scheme to get carbon emissions down as quickly as possible. The central goals of these plans are to reduce a community’s contribution to climate change as much as possible and to strengthen the community so it’s prepared to deal with some of the problems that climate change is already bringing.

What are some of the problems that climate-action plans are designed to address?

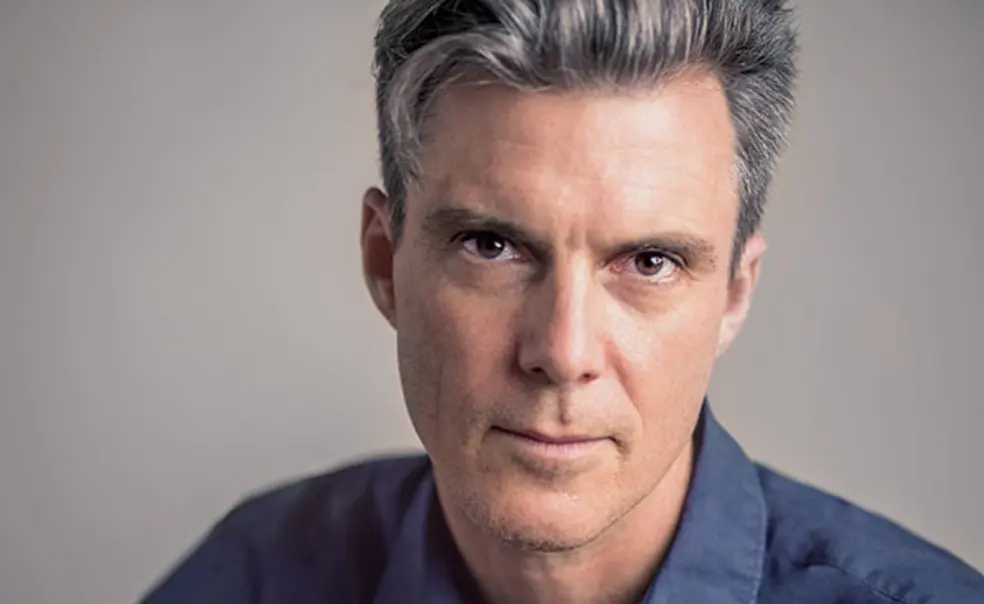

“The real task is to get off fossil fuels entirely.”

— Ashley Dawson, visiting professor in the environment and humanities

A lot of problems caused by climate change are exacerbated by social and economic inequality. For example, one of the ways that climate change will affect people is through rising temperatures. And this is a place where people’s access to resources matters: If you’re elderly and you can’t afford to run your air conditioner 24/7 during a heatwave, you may die. So making sure that people can pay their electricity bills, that their homes are well insulated — these are issues to think about.

What are some ways that communities can effectively reduce their carbon emissions?

Every plan has to be different, but the real task is to get off fossil fuels entirely, and that means switching to renewable energy like solar and wind. We need to create micro-power grids so that communities can be resilient in the face of a climate emergency. Community gardens in urban areas can serve as buffers for flooding, and when they’re on roofs, they have a cooling effect. You want to be strategic and think about how these technologies or resources can benefit communities in multiple ways. Community gardens, for example, can provide food.

What can Princeton learn from other plans that have been successfully implemented?

Princeton is still in the information-collecting stage, which is very important because each plan needs to be specifically tailored for its place. But certainly, it can learn from other exemplary plans, like the North Manhattan Climate Action Plan in New York City. That plan addresses the problem from many angles. It calls for affordable housing for vulnerable populations, new coastal protections to prevent flooding, and better urban design for pedestrians and bicyclists. And it brought together several communities around Harlem. Princeton might similarly think about how it can facilitate collaboration between the town and the University.

What are common challenges that localities face as they create and implement climate-action plans?

Hollow promises are a big challenge. When a city says it’s going to get rid of emissions by 2040 or 2050, it’s not always clear how that will be done. There need to be concrete interim goals. And the plan should address broad community needs. If you’re putting in more solar power, make sure it’s going to working-class neighborhoods as well as affluent neighborhoods. Make sure that installation of renewable energy creates jobs in local communities that pay a living wage. And finally, you need to educate people about what’s going on and get their buy-in. It’s not enough to have a plan if you don’t have the community on board.

Interview conducted and condensed by Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux ’11

1 Response

David Baraff ’66

7 Years AgoMere Speculation

Ashley Dawson perpetuates the nutty idea that science can accurately state that mankind is responsible for global warming. Because the physics of climate is not well known, climate change can not be rigorously calculated. In addition, the calculations if possible would require that the initial state of the system to be well described, which it's not at present. Therefore, the "scientists" have created models of the climate with semi-adjustable parameters. These parameters are changed to fit what little past data is known. The idea that these parameters will be sufficient to predict climate 100 years into the future is mere speculation, and the idea that the effects of CO2 are determinate has not been proven. Unfortunately, the amount of money the government has pumped into the climate science community has corrupted its judgment. The scientists in this community are discrediting real science.