Q&A: Professor Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97 On James Baldwin and Today’s Protests Against Racism

This spring, as the nation erupted in protests over systemic racism, Princeton professor Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97 felt that the country “was at a crossroads,” he says. “We have an opportunity to make a choice to be different as a nation, to allow a new America to come into being. But we have faced other moments of reckoning.”

Glaude, who is the chair of the Department of African American Studies, spoke to PAW about the ways America’s identity is distorted by prejudice and how a push for change in the United States has so often been followed by retrenchment.

How did this moment make you reflect on the relevance of Baldwin’s work today?

When I saw that knee on George Floyd’s neck, I saw the smugness on the face of the officer and the complete disregard for the human being under his knee, it threw me back to Jimmy Baldwin; and a line came to mind from an interview he did with [civil rights leader] Ben Chavis in 1979 or ’80, when Baldwin said, “What we are dealing with really is that for Black people in this country, there is no legal code at all. We’re still governed, if that is the word I want, by the slave code.”

Is it troubling for you that his insights are still relevant?

When it comes to race, we’re always tinkering around the edges. Baldwin said the true “horror is that America changes all the time, without ever changing at all.” My son is experiencing this. I experienced this. My father experienced it.

You write that another of Baldwin’s observations remains true: Our country reinforces false ideas about American identity.

Baldwin talked about categorizing ourselves — in terms of color, in terms of whiteness, in terms of being heterosexual — as a trap. He tried to disrupt the categories that get in the way of seeing the humanity of the person in front of us.

We are a profoundly racist society, and we hide behind our innocence to keep us from confronting that fact. It’s not just simply the loud racists. It’s not just simply Donald Trump. It’s easy to scapegoat Trump and make him exceptional, but we’re making choices day in and day out to reproduce the kind of society that makes Trump possible. We need to tell ourselves a different story of who we are, to put aside this notion of a city on a hill. We have to finally confront the ugliness of who we are.

You compare Trump’s election following Barack Obama’s with the period that began with the civil rights movement and ended with Ronald Reagan’s election: A push for change was followed by a pull to preserve the status quo. Why has that happened repeatedly in American history?

In the moments when the country seems to be on the precipice of change, we have doubled down on the ugliness of whiteness. We’ve had previous moments of moral reckoning. The first was the American Revolution. Black folks who fought in the Revolution drew on the principles of the Revolution as a way of arguing for their own freedom, but the nation doubled down on the idea that whiteness mattered more than freedom and liberty. What do we get after Reconstruction? We get Jim Crow laws and convict leasing [the practice of leasing out inmates to do dangerous manual labor for private companies].

Coming out of the nonviolent demonstrations of the ’60s, we saw “tough on crime” and “the war on drugs,” which led to an aggressive form of policing and the militarization of police. For 40 years, we have been living in that frame.

How do you see the eruption of protest now?

It’s accumulated grief and suffering. An explosion of anger in a moment is never simply about that moment. It’s always a part of an accumulated experience of disregard and accumulated suffering. The tinderbox that is America only needed a spark, and there it was. The other dimension, which is really important, is the ongoing grassroots organizing in the country. Black Lives Matter went underground after the election of Trump, but it has still been organizing. Other justice-reinvestment movements, groups for gun control, are all organizing. It’s not just spontaneous. The civic work is going on, and we are seeing it made manifest in this protest.

Do you feel any optimism that we may be headed for real change?

I’m never optimistic. I’m too much of a pragmatist. But I’m hopeful. We see a movement, but there’s no guarantee of the outcome.

I hear different voices: One voice prefers civility over justice, the disruption of protest unnerves, and they are clamoring for quiet. Then you have folks who are clamoring for reform, but they want to tinker around the edges — reform with a mind to keeping the status quo. Then you have the voices of fundamental transformation. They understand white supremacy continues to distort and disfigure democracy. That cacophony is all being heard at this moment, and there’s no guarantee we’ve broken through. No guarantee that matters will fundamentally change. Only that we must continue to fight for a more just world. Interview conducted and condensed by Jennifer Altmann

3 Responses

Tenley E. Raj ’07

5 Years AgoLove and Logic

Cornel West *80 speaks about supremacy and the likely white backlash eloquently and, in my opinion, pretty accurately (his recent interview in The Washington Post Magazine is a nice one). Professor Glaude, I don’t think basically calling any race ugly (“we have doubled down on the ugliness of whiteness”) is a good way to bring people together. I now reread your words: “Baldwin talked about categorizing ourselves — in terms of color, in terms of whiteness, in terms of being heterosexual — as a trap. He tried to disrupt the categories that get in the way of seeing the humanity of the person in front of us.” Hmm. Maybe we could “disrupt” with love while also positively inspiring people to come together? Yes, we can!

Susanna Badgley Place ’75

5 Years AgoSuggesting a University-Wide Course on Confronting Legacy of Structural Racism

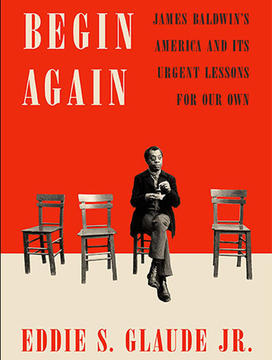

I’m deeply grateful to Professor Eddie Glaude Jr. *97 (On the Campus, September issue) for contributing Begin Again to the American conversation about the desperate need, and rising calls, to address the chasm between professed values and reality in this country. As a student of revolutionary history in the mid-1970s at Princeton, I nevertheless managed to graduate without an understanding of my own historical and ideological roots as a white American.

As Glaude says in this interview, we can no longer “tinker around the edges” and try to appease protesters with incremental change. I suggest that Princeton, “in the nation’s service,” should institute a Universitywide (required) course that studies structural racism and taps into important national (or international) efforts to address and change the course of our national priorities and programs. Such a course would be a great start and commitment to the (re)education of our Princeton community, current students and alums. Princeton, within the vast American academic community of resources and voices, can begin to make a profound and enduring change in American life and its future.

Norman Ravitch *62

5 Years AgoRacism and Revolutionary Change

While I have not read any of Professor Glaude’s works I have seen him on television frequently and appreciate his intelligent comments and his critique of many American delusions. Yes, we are not a City on a Hill, largely because all biblical allusions refer to a human race not in fact really here or there. It is easy enough to take on the trappings of virtue and morality without worthiness; the Bible calls that pharisaism, even though the Christian view of the pharisees has been shown by historians to be bigoted anti-Semitic observation based on little truth.

Glaude says he is not an optimist and I agree that optimism is not called for in our discussion of racial matters today. But he seems to buy the notion that revolutionary change is both good and moral, even if it is not necessarily around the corner. I would differ by claiming that revolutionary change is rarely good, often disruptive, and that the result is often worse than the disease in the first place. This is Burkean, and while Edmund Burke in his own day was ridiculed as an Irish lap dog for factions of the British aristocracy and one who saw the French Revolution less through proper glasses than through myopic lenses, in time his sort of conservatism was generally held to be more practical, more moral, less dangerous and more commendable than the versions found east of the Rhine River or south of the Mason-Dixon Line.

My own lack of appreciation for James Baldwin could be considered evidence of my racism, but actually it is admission that white people still have trouble with Black people for many reasons, not all or most of which are racist; most problems whites have with Blacks, and Blacks with whites, are based on early experiences with “the other” which have left damage in our brains and our souls, things which are very hard to deal with and correct if ever and which politics surely will fail in the endeavor.