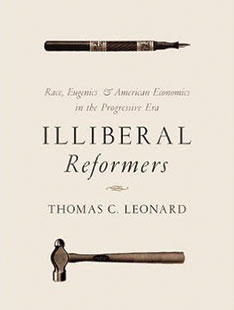

Sound like 2016? Try 1900. And these weren’t conservatives. These were progressives. “They described it as a revolution, the likes of which the world had never seen,” says Thomas Leonard, a research scholar in the Humanities Council and a lecturer in economics at Princeton and author of Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics & American Economics in the Progressive Era (Princeton University Press). While corporations were checked and progressive presidents Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson 1879 were voted in, the Progressive Era — 1900 to 1920 — was marred by a darker history of racism and xenophobia among its politicians. The legacy of that racism surfaced on Princeton’s campus last year with a call by student activists to remove Wilson’s name from its public-affairs school and a residential college.

They established economics as an academic discipline, while promoting and helping build regulatory and independent institutions such as the Federal Reserve (1913), the Federal Trade Commission (1914), and the International Trade Commission (1916).

Leonard shows, however, that their policies were undergirded by social Darwinism and eugenics and excluded groups deemed inferior — including women, Southern- and Eastern-European immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and blacks.

“They wanted to help ‘the people,’ but excluded millions of Americans from that privileged category on the grounds that they were inferior,” he says.

Progressives pushed for voter registration, literacy tests, and poll taxes to mitigate fraud and corruption, bolstering the Jim Crow South. In 1913, they proposed a minimum wage to benefit skilled Anglo-Saxon workers by requiring immigrants to prove they had a job paying that wage to enter the country.

Leonard began researching the origins of the minimum wage in 2001. “I was forced to confront the fact that race and social science intersected in complicated ways,” he says. “The entanglement was significant and deeply rooted in the Progressive Era.”

He wrote Illiberal Reformers to re-evaluate a crucial moment in American history, but found it surprisingly relevant today. “I finished the book before the rise of Donald Trump and the nationalist and populist movements in Europe,” he says. Those movements are also characterized by dissatisfaction with rising inequality and perceived corruption; moreover, they are anti-immigrant, and sometimes openly racist. “If you would have asked me in 2015 about a wholesale return to illiberalism, I would have scoffed,” says Leonard. “While economic historians tend to focus on class, you can’t look at political and economic reform without understanding the complicated ways race and class intersect.”

No responses yet