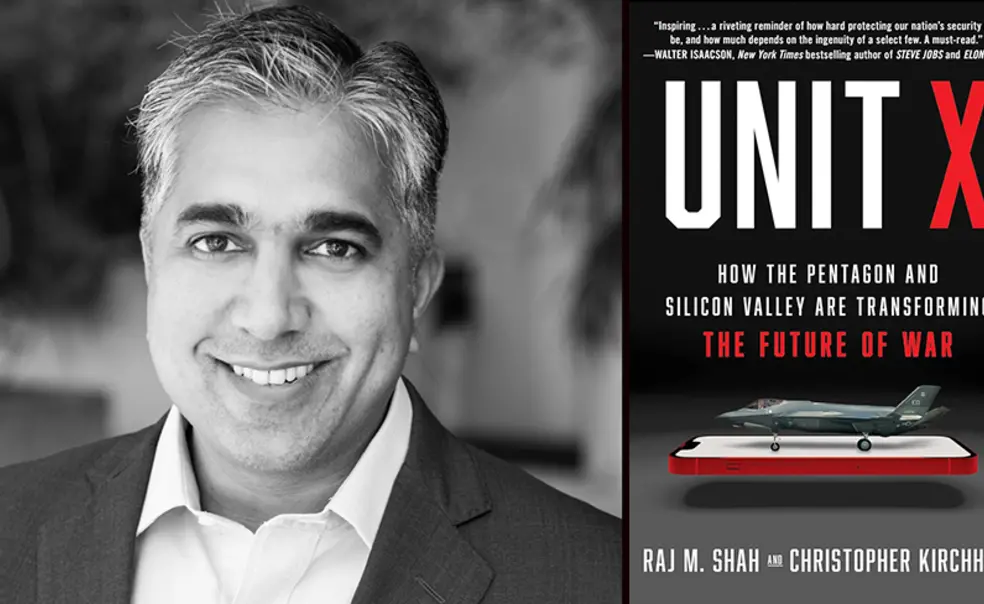

Raj Shah ’00 Co-Wrote a Book on the U.S. Military and Silicon Valley

In Unit X, Shah describes his efforts to bridge the divide between the military and producers of cutting-edge commercial technology

In 2006, Raj Shah ’00 was a U.S. Air Force pilot flying an F-16 on the border between Iraq and Iran. The plane was a marvel of engineering, but its navigation system was so outdated that it couldn’t tell Shah which side of the border he was on — a potentially fatal flaw. When Shah returned from the mission, he loaded civilian navigation software and digital maps onto a simple handheld electronic device that he used on future flights.

For Shah, the experience crystalized the difficulties the U.S. military has had in incorporating even basic technology into the fighter jets, submarines, and aircraft produced at great expense by large defense contractors.

For much of the last decade, Shah has worked to bridge the divide between the military and producers of cutting-edge commercial technology, as he describes in his new book Unit X: How the Pentagon and Silicon Valley Are Transforming the Future of War, which Shah wrote with Christopher Kirchhof, a former adviser to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In 2012, Shah helped start Morta Security, a cybersecurity company sold to Palo Alto Networks in 2014. At the time, “It was so hard to sell to the government that our investors advised us not to work with them,” says Shah, who is still in the Air Force reserves. At Princeton, Shah graduated from what’s now called the School for Public and International Affairs, then went to Air Force Officer Training School. When he left the Air Force, he went to the Wharton School, but remained a reservist.

Ash Carter, then the defense secretary, had perceived that difficulty as a serious problem for a generation. In 2016, he tapped Shah and Kirchhoff to run the newly formed Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIU) to address the issue.

The byzantine budgeting process at the Department of Defense is a significant barrier. It can take four years on average to win a government contract, Shah says, while startup companies need to demonstrate progress to raise capital every 18 months. The process was designed with large government contractors such as Lockheed Martin, which makes the F-16, in mind; entrenched interests at the DOD and Congress often favor large contractors even when they have subpar technology or are poorly suited for a task.

“If your amazing technology is a sub or a fighter jet,” Shah says, “you need a large company. But as you move to software, drones, and [AI technologies] with shorter development cycles, you need smaller, more nimble companies.”

Shah and the team at DIU identified a number of those companies in his time with the group, such as Saildrone, which makes “self-powered autonomous sailboats,” Shah and Kirchhoff write. Drones and artificial intelligence are already remaking warfare, as has become clear in the war in Ukraine, and they will continue to do so, meaning that the U.S. military has to invest in those technologies to remain competitive, they argue.

“AI will drive geopolitics in the same way other empires have risen and fallen on gunpowder, the steamship and steel,” they write.

Shah left DIU in 2018 and late that year started Resilience, a cyber insurance and security company. In 2021, he launched Shield Capital, an early-stage venture capital firm that invests in start-up companies whose technology has both commercial and military applications.

Shield has partnered with large defense company L3 Harris Technologies to invest in promising companies, a sign that the division between the so-called primes and start-up companies may be fading. “You need an ecosystem of young companies, and you need established companies that have permanency, security clearances, trust, and ability to work with the government,” Shah says.

He also sees far more enthusiasm from company founders. “I’ve never met [so many] entrepreneurs who want to work in national security,” Shah says, noting that venture capital firms have invested $140 billion in national security startups in the last three years.

“I think there is also a desire among founders to do something that has meaning and helps preserve democracy and freedom,” he said, adding later in an email: “This mission provides that, and also represents interesting, difficult technical problems.”

No responses yet