Rally 'Round the Cannon

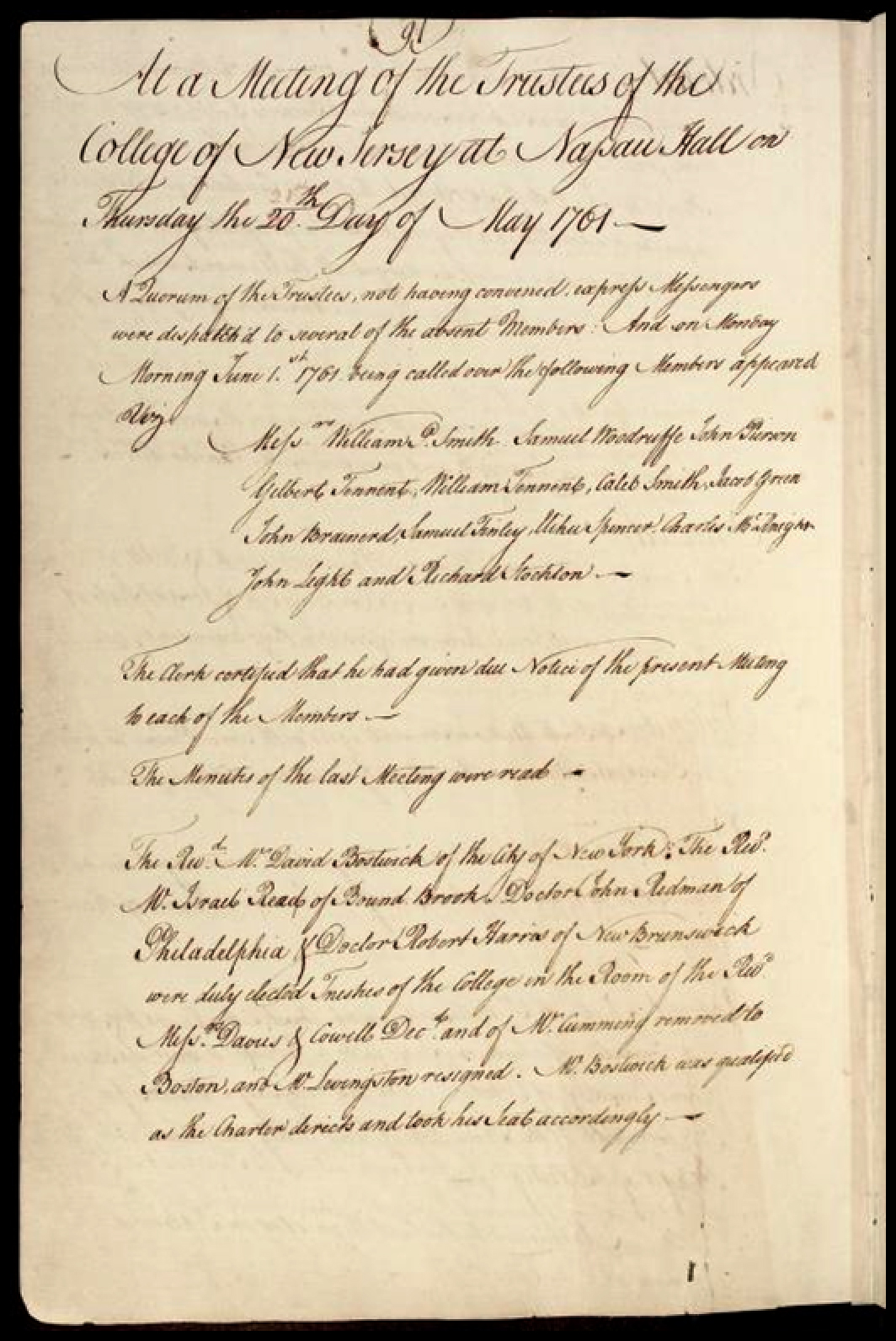

College trustees’ minutes: fundraising, investing – and finding a leader

America is a young country with an old mentality.

– George Santayana

One of the few irksome aspects of hanging out here at History Central (George Santayana, Prop.) is that despite our zippy digital trappings, casual readers seem to feel we’re a bit out of touch with cutting-edge developments, like tweets and indoor plumbing. Nothing could be further from the truth, except maybe the platforms of the major political parties. Take the Royal Wedding; we’re just as breathlessly distracted by the pomp and glitter as anybody else among the paparazzi, and just as eager to bring you all the tasty tidbits regarding the Happy Couple and their magical adventures.

Of course, in our case it’s George III and Princess Charlotte, who got hitched in 1761. But when you think about it, this gives us a huge advantage, in that we can gossip pretty convincingly about their 15 kids [not bad for an arranged marriage] and his spotty prospects in the realms of both mental health – see The Madness of King George sometime – and North American landholdings, which took a hit with some enthusiastic help from Old Nassau in 1776.

But today we note the wedding, and the other tasty morsels from precisely 250 years ago in 1761, and focus on a Wayback Machine in which you can travel there and take a look around. It was a different world and then some – no democracies, no electricity, no PAW; but plenty of slavery, disease (remember that), and fancy-dress royals. The French and Indian Wars were rolling along in the American interior, giving George Washington p1799 some military training, which later would prove useful. In the arts, the baroque was about to give way; Handel had been dead two years, Gluck was finishing Orfeo et Euridice, and Mozart was a wildly precocious 5-year-old who already was composing. Thomas Jefferson was a junior at William & Mary.

The Wayback Machine? Well, our good friends in the University Archives have put a nice selection of old trustees’ minutes online, and we call your attention to them as a way to access and consider this alternate universe; for fun today we go back to 1761 and take a look around.

Of course, including the terms “trustees” and “fun” in the same sentence might seem a reach, but just look at the enthusiasm of the current cohort

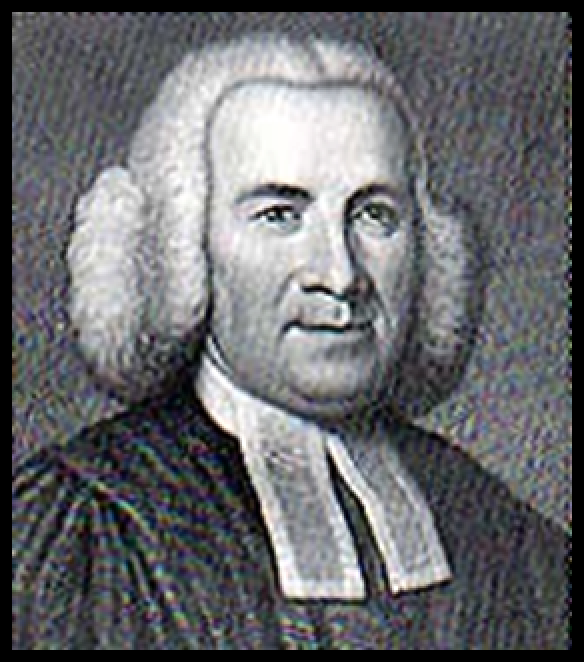

At the time, Nassau Hall (then occupied for just five years) had not proven hospitable to authority: Three presidents had died in rapid succession during those five years, and the board was going for a fourth. Aaron Burr Sr., who unexpectedly had picked up the mantel in Newark in 1748 and overseen the second college charter, the construction of Nassau Hall, and the move to Princeton, died one year thereafter in 1757, only 41 years old and exhausted. The trustees then did their part for medical history – although not the Enlightenment – by inoculating at his inauguration the great Jonathan Edwards, voice of the New Lights, against smallpox, of which he immediately died in 1758. After next electing New Light hymnist and preacher Samuel Davies, it took them a year to convince him to come. This showed insight on his part; 18 months after finally acceding to Princeton, he was bled for a bad cold and died of pneumonia (remember the disease?) at age 37. Five weeks earlier, he had preached on Jeremiah 28:16: “This year thou shalt die.”

So while the September 1760 trustees’ meeting at September Commencement had decided that “every student shall be obliged to reside in College at least Two Years before his first graduation” (which remarkably is still the case) and that “After the present Year all who are admitted into the Freshman Class shall be acquainted with Vulgar Arithmetick” (harder to prove, certainly), by June 1, 1761, they had to focus on a new target , uh, leader.

Elsewhere in the minutes, we find the unoccupied interim had not gone well at what today is Maclean House: The trustees “do strictly forbid … Persons belonging to the College playing at Ball against the said President’s House.” The fine was five shillings.

The following meeting was September 30, 1761, at Commencement, with Finley present. In addition to the 14 graduating seniors, the board voted three master’s degrees, including one to trustee and Finley’s fellow Log College alumnus William Tennant Jr. The board cited the ongoing lottery in Philadelphia for the benefit of the College (remember the fundraising?) and directed the immediate investment of the proceeds (remember the investing?). Students also were periodically weaseling out of tuition payments at school-year’s end, so the trustees decided if they didn’t pay at the beginning, they had to post bond; sort of an in loco carcerensis clause. Fees, by the way, were set at 25 pounds 6 shillings per term, including two pounds for firewood and candles; perhaps $13,000 per year in today’s money (although keep in mind the food was Spartan, the pump and the outhouse were – uh – out, and daily chapel was a requirement).

Finley, as it turned out, outlasted his three predecessors combined in Nassau Hall, five years; the college grew and graduated 130 students in his time – including the founders of Brown and Hamilton colleges, a New Jersey governor, and a Supreme Court chief justice – foreshadowing many secular student and alumni adventures to come. His academic credentials were so impressive that in 1763 he became only the second American awarded an honorary doctor of divinity degree in the British Isles, at the University of Glasgow. This set the stage in Princeton for his game-changing successor: the Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon from Paisley.

So we find in the trustees’ minutes that a quarter-millennium ago things were really getting perking around the new Nassau Hall, pointing toward the College’s future contributions to the not-yet-a-country. Of course, 15 years later it would become ground zero in actually establishing the United States as the British and Americans fought over it. And exactly 100 years later, it would see the disassembling of that country in very likely the most wrenching period in its life.

In our next column, we look at 1861 and the onset of the Civil War.

No responses yet