“Just being a woman doesn’t mean I don’t have ambitions to be the pope or the emperor.”

– Willa Cather

Here we are, plunging yet again into the staid predictability of commencement season, with a torrent of colorfully bedecked jobless youngsters spilling out into a mysterious world, with more platitudes than in all of Australia (as Dad used to say, which is one reason I rarely quote him), with the Tigers and the Cantabs tactfully bringing up the rear in early June.

Given the paucity of original thought involved, you might not expect this to be fertile ground for historic rumination – especially given Princeton’s admirable strategy to forgo outside graduation speakers, figuring that what can’t be overstated at Baccalaureate and Class Day isn’t worth overstating. There is, however, one ceremonial facet I’ll readily admit to being a sucker for, that has within it an irresistible combination of perversity and pomp to quicken the hearts of name-droppers everywhere.

You just gotta love the celebrity honorary degree, academia’s simultaneous retort both to papal elections (look, Edna, the smoke!) and Oscar night.

Don’t misunderstand, I have no illusion about worthiness. In a just world, every Princeton faculty member who survives 20 years would earn an automatic Litt.D. with a 10 percent pay bump, a locomotive, and a case of single malt. Every minister to the poor and destitute would get an orange-trimmed academic gown with sewn-in elbow pads and a million bucks for his or her favorite charity. However, it’s beginning to seem that this is not the true nature of our universe, so in their place I must admit to fascination with the proud few colorful cultural icons who do make it to the podium, to have their lives recounted in stentorian tones.

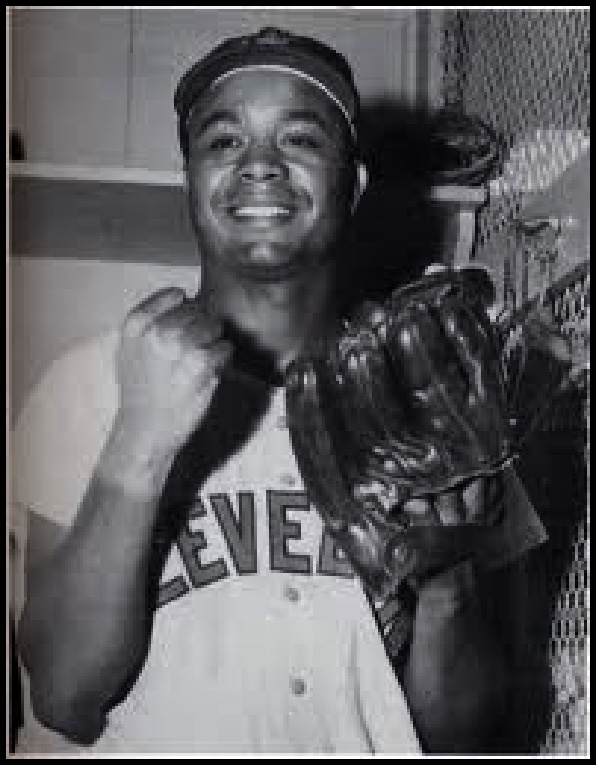

Bob Dylan received a Princeton degree at my graduation in 1970 (“now approaching the perilous age of 30”), seemingly either impressed or distressed enough to not accept another for the rest of the century. Stephen Hawking’s degree in 1982 was a nice mirror of Albert Einstein’s in 1921 (“voyaging through strange seas of thought alone”). I was ecstatic in 1998 when my thesis adviser, John Tukey *39, was given one, if only as recompense for the years I took off his life, and in 1997 when my childhood hero, New Jersey’s own Larry Doby, was honored 50 years after enduring his private hell of being the American League’s Jackie Robinson.

Speaking of real pros, here’s my favorite honorary-degree story, which shouldn’t be any less entertaining for being true and hopelessly unscholarly. A young friend from Chapel Hill, N.C., graduated in 2001, and his true-blue Carolina grandmother, rabid veteran of many years of the Dean Dome and SportsCenter, made her first trip to Princeton for the occasion. Ambling down McCosh Walk toward Front Campus for the ceremony, grandma, father, and graduating son came upon three tall people walking side-by-side in the other direction: Bill Bradley ’65 h’83, Bill Walton p’01 (whose basketball-captain son was graduating), and Bill Russell h’01, there for his honorary D. Hum. They all just kept walking, but after a considerate pause, grandma firmly stated her conviction that this was indeed a very interesting place.

The trustees can give an honorary degree – along with the traditional oral citation begun in 1905 by Andrew Fleming West 1874, dean of the graduate school and nemesis of president Woodrow Wilson 1879 – to essentially anybody they please. Retiring Princeton presidents usually get one (even Wilson, when he quit following his pitched battle with West), new Harvard and Yale presidents, too (Drew Gilpin Faust k’42 last year), distinguished retiring senior faculty, various Nobel Prize winners, renowned artists, public servants, captains of industry, scientists, statesmen. Bill Russell extensively fulfilled the only true requirement, ensconced in the University’s bylaws since 1895: You have to show up and receive it in person. Traditionally, in large part because of that one requirement, another rule has evolved; honorands’ names never are revealed in advance and they are cautioned into keeping mum, lest they not turn up for some reason at the last moment and thus are disqualified.

For the first 183 Princeton Commencements (Royal Governor and college benefactor Jonathan Belcher received the first honoris causa in 1748) there was another tacit tradition: The hundreds of recipients were unrelievedly male. In addition to the 10th anniversary of Russell’s degree, this year we note the 80th year since the first woman received an honorary Princeton doctorate at Commencement. Given that landmark gesture, you might be surprised that today this outstanding lady perhaps might be known at best by half the graduating English majors, and almost nobody else. She was the woman who felt qualified to be pope, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Willa Cather. A child of Nebraska, and graduate of its university when it was but 25 years old, she always contended that what you write is determined by the time you’re 15 years old. Her three novels of the 19th-century prairie – Oh Pioneers! , The Song of the Lark , and the famed My Antonia – used a truly American voice in a way only a few such as Mark Twain, Jack London, Theodore Dreiser, and Upton Sinclair had before.

Cather’s sponsor at Princeton, the great Chaucer scholar Robert K. Root (one of Wilson’s original preceptor guys in 1905), noted, “Her art is distinguished first of all by an inexorable sense of truth … Her prose disdains the tricks of clever epigrams and superficial ornament.” He pestered the trustees through grad school dean Augustus Trowbridge until Cather was offered a degree; what’s truly remarkable about their exchange was that her being a woman was never mentioned or discussed. Root didn’t care either way in a literary sense, and Trowbridge felt no reason to consider it an impediment to a degree. Clearly, it was time. Although she had received other honoraria previously, Cather always insisted that this was her favorite degree, simply because “she received more applause than Charles Lindbergh.” Why has this evocative writer – I’d compare her to today’s Garrison Keillor, a recent Baccalaureate speaker and another of my personal idols – fallen into disuse? Perhaps her painstaking portrait of the early prairie was supplanted by the powerful naturalism of writers like John Steinbeck and Tennessee Williams; perhaps her world is hard to find through the legends of Clint Eastwood and John Wayne; who knows? As an artist, her time will come again, all good artists’ do, and when it does Root and Princeton will be there to attest honoris causa .

But seriously now, what does all this with the exacting secrecy and regalia really amount to? Well, of course many of the great educators and scholars we recognize with honorary degrees are powerful symbols of the academy, whose recognition gives us pause to think about thinking. But many other honorands are there in some attempt, I suppose, for the University to indicate its values and standards, and in return hopefully flatter and promote those it honors. Or be nice to alumni. Or to somebody’s grandma. Or Dean Root, or whomever.

Anyhow, tune in live at Princeton.edu May 31 and find out; it’s secret until then. Of course, I could tell you the names, but then I’d have to send the Triangle kickline (attired in caps and gowns, of course) over to kill you.

No responses yet