Indiana, we are simply passing through history.

This [Ark of the Covenant]: This is history.

– Rene Belloq, Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981

While Bill Bradley ’65 was my U.S. senator, he once held a book-signing (imagine, a literate legislator) and informal constituent meeting here in his New Jersey hometown. In response to a question, he launched into a reflection on the flowering (in the verdant Garden State) of many and copious complexes of household-storage facilities, and decried the culture’s deconstruction into a meandering band of highway travelers, condemned in perpetuity to Sisyphian SUV journeys past miles of lockers, breathlessly pointing out to fellow inmates of our vehicles, “My stuff is in there! That’s my stuff!”

As spot on as Dollar Bill was, and as supportive as I am of that view of consumer culture run amok, I grudgingly will admit, especially today, that not all stuff is created equal. That’s primarily because Jan. 6 is Bill Scheide’s 100th birthday.

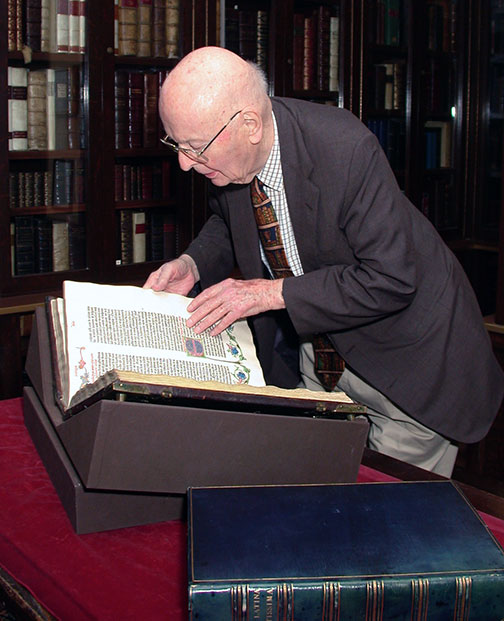

Of the hearty sprinkling of alumni – 18 that we know of, based on records in the Archives and current alums – who’ve reached that milestone over the centuries, William H. Scheide ’36 certainly belongs in the inner circle of the very heartiest. He and his wife, Judy McCartin Scheide (an honorary ’36 classmate), continue to pursue a lifetime of institutional largesse, from Scheide Hall at the Seminary, to the Scheide Recital Hall and the Scheide Student Center at Westminster Choir College, to the Mendel Music Library he built at Woolworth in honor of his Princeton music professor, to the Scheide Caldwell House of the Andlinger Center for the Humanities on the front campus. And, most stunningly, as the owner and benevolent despot of the Scheide Library, housed at Firestone in the Rare Books and Special Collections neck of the woods, he is very likely the reigning qualitative authority on our planet as regards stuff.

The Scheide Library is a bit hard to describe to proper effect. Its copies of the first four printed Bibles in the world are the only existing full set in private hands, and that tends to be a conversation-stopper regarding the other marvels on the shelf, including everything from unique Bach manuscripts to an original printing of the Declaration of Independence, to letters of Christopher Columbus to multiple 17th-century Shakespeare folios, perhaps 2,500 volumes in all. Not only couldn’t the collection be reproduced, it would be hard to even locate many of the individual items elsewhere – their gathering having begun well over a century ago by Scheide’s grandfather, William T. Scheide, business compatriot of John D. Rockefeller the Original and (you’d better believe) person of taste. His son, John H. Scheide 1896, was not healthy enough for business, so he spent his life focused on the Library holdings, and his musically oriented son, William H., pursued it from there. In the 60 years – an almost unheard-of active span for a sole collector – since his father’s death, Bill has taken a unique assemblage, moved it to Firestone, and turned it into a monument to the great ideas of Western Civilization and beyond.

Which is what we’re here to talk about. Although the Scheide Library is undeniably stuff – to a degree that mesmerizes – it’s really something else in stuff’s clothing; there’s great creative intellectual drive constantly in motion just below the surface. The tip-off is the music. What you see are scores by Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and especially Bach. What Bill hears is the color, the richness of the emotion, the humanity. He is a Bach scholar, published in pre-eminent journals. When studying and teaching music in the 1930s, he ran across a slew of Bach cantatas that were virtually unknown at the time; by 1946 he had founded the Bach Aria Group to perform them, and so undergirded the resurgence of the master much as Mendelssohn had done a century before. And of course there’s his longstanding devotion to the Choir College. We’ve talked before of the transportive aspects of music – not to mention in this case the breathtakingly illuminated Bibles and other intellectual treasures – and that is precisely what Bill and the Library offer us, not just vellum and dust. It is living, enthusiastic history, stopping just short of Indiana Jones’ Holy Grail (originally a project of Jones’ father, come to think of it).

Consider: A few years back, a papal indulgence (remember the Reformation?) printed by Gutenberg appeared at a German auction after a century in hiding. Bill’s father already had acquired one for the Library in the ’30s, and they’re not exceedingly rare, at least by Scheide standards. No German library was really interested in it – among other shortcomings, it was fragmentary – but Bill snapped it up (if that’s what you do with 600-year-old vellum documents) for a blindingly straightforward reason: The buyer’s data were written in when it was issued; Margaretha Kremer purchased it in Erfurt on 22 October 1454. So this document is the first dated instance of printing in all of Europe, utterly unique. This type of insight and curiosity continue as Bill selects and acquires items to this day, as much sleuth and imagineer as librarian.

If you regard that as a bit cerebral, Bill has his more practical side as well, and applies to it the same good judgment, aesthetic, and imagination. After a conversation with young lawyer Thurgood Marshall in the 1950s, he bankrolled the landmark lawsuit Brown v. Board of Education and subsequently became a senior director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and a stalwart of Princeton’s Joint Commission on Civil Rights. He’s been a major contributor to, and board member of, a dizzying range of local and regional charities and social-service groups, as well as trustee of both the Seminary and Westminster. Each year, for his own birthday, Bill holds a concert for friends; in his case, this means a charity event in Alexander Hall with, oh, maybe the English Chamber Orchestra or the Bach-Collegium Stuttgart performing; the beneficiaries have ranged from Isles Inc. (fostering community development in Trenton) to Centurion Ministries (freeing unjustly convicted inmates) to the Princeton recreation department. This month’s concert for his 100th birthday will be a wowzer: Westminster’s Symphonic Choir, along with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra (Mark Laycock will conduct), performing Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture, a Bach cantata chorus (surprise), Bill’s own “Prelude for Piano Four Hands,” and Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony to benefit the Choir College. If An Die Freude ever fit as the theme for an occasion, this one certainly qualifies.

The exuberant – and let’s be fair, authoritative and insistent – spirit that Bill brings to the party makes it seem perfectly reasonable to have him around for a 100th birthday celebration, but still it’s really unusual, in the same rarefied sense that the Scheide Library is “unusual.” So to do justice to his personal depth and import might be problematic, except that his own website supplies an excellent exposition:

“Bill Scheide is a musician, philanthropist, and humanitarian. His life-long support of the arts, education, civil rights, health, and poverty-relief programs expresses Bill’s belief that each member of the human family deserves a free and enlightened life.”

And if there’s some special stuff in the Library that can help him accomplish that, who are we to quibble? If I were to run into a freudig Bill Bradley at the Scheide concert on Jan. 25, it wouldn’t surprise me in the least.

For those who arrived here at the ever-exciting Rally page via the theme of this year’s special January issue – privacy – you also may wish, in that spirit, to revisit my column from the fall regarding the NSA, IDA, and alumni and faculty involvement in America’s current debate on the issue. We’ll be watching; we know who you are.

No responses yet