Tinsel, Glitter, and the Transformation of Princeton

Tinsel, Glitter, and the Transformation of Princeton

Shoot a few scenes out of focus. I want to win the foreign film award.

— Billy Wilder

In considering our loss last year of the happy warrior Peter Lewis ’55, you can read Fran Hulette’s good piece in Your Favorite Periodical or take a look at his striking talk on philanthropy to the City Club of Cleveland, in which he notes the words of Old Nassau: “Her sons will give.” In my case, I wandered by his new Lewis Center for the Arts and, since it’s still in the dodge-the-front-end-loader-on-your-way-to-the-temporary-Dinky stage, thought about its great potential, especially given Princeton’s surprising contributions to the arts over the 267 years we didn’t have the Lewis Center. Or much else, really: For the last few decades, the hot spot of our fine-arts creative activity has been an old grammar school building discarded in the ’60s by the Borough.

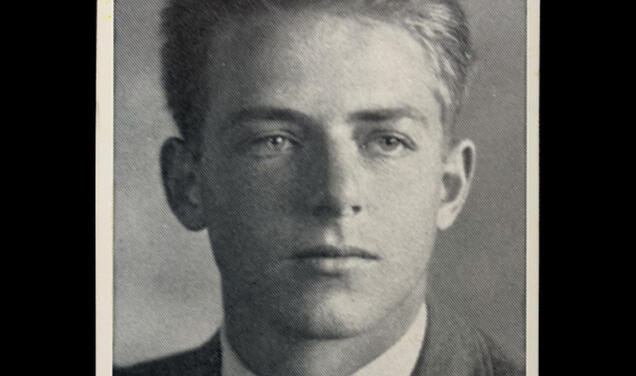

A serendipitous artistic case in point is everyone’s familiar hero, James Maitland Stewart ’32, who came to Princeton because it was a family thing, fell in with sordid Triangle companions (Josh Logan ’31, Jose Ferrer ’33 , you know the type), and built for himself a global career portraying honest and earnest men, and letting his own personal good sense overrule the temptation to fall in with the dreamweavers of the Hollywood public-relations world. Such was his influence that studio mogul Jack Warner, who did not become one by misjudging personalities, was moved to observe, “You’ve got it wrong. Jimmy Stewart for president. Ronald Reagan for best friend.” Stop sometime when you’re watching Vertigo or Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or Anatomy of a Murder and chew on that. If the old-school preppy image of Princeton, hyper-accelerated by the siren song of Scott Fitzgerald 1917, had continued unabated through the ’50s and ’60s without the substantive softening of Stewart’s persona, it’s hard to imagine how much more difficult the transition to a modern-day university might have become. And for this great blessing, Jimmy Stewart was indeed recognized by the dedication in his honor of a lovely performance space – in the old grammar school building at 185 Nassau Street.

So, although you’re killing time here in Virtual History waiting for the Oscar telecast to begin on March 2, Your Favorite Periodical is likely not top-of-mind on your checklist of necessities for the ceremony – it likely comes way below popcorn, if a bit above your Sound of Music commemorative dirndl – but surprisingly, we offer an intriguing look back to a pivotal moment 40 years ago when the Motion Picture Academy itself was trying to deal with a new, young media-savvy audience, and somehow ended up in Tigertown.

In the early ’70s, the Gatsby persona was a significant concern to the University, newly coed, newly multi-ethnic, newly just about everything. This had two distinct and virtually antithetical effects: Many of Princeton’s older constituents (read: crotchety alumni) were panic-stricken and started efforts like the Concerned Alumni of Princeton to shovel against the tide of history and attempt somehow to return the College, uh, University to a world that never actually existed; meanwhile younger targets (read: high school juniors) couldn’t figure out what Princeton and the other Ivies were if 1), they weren’t what they used to be and 2), they weren’t what Berkeley or Ann Arbor or MIT was.

In the years since the complete fiasco of Fidel Castro’s visit to campus in 1959, a number of public-relations challenges had arisen for Princeton: the $53 million capital campaign; the spring riot of 1963; five years of civil-rights, anti-war, and IDA demonstrations; the approval of coeducation; the strike of 1970. The communications office and the development office, though still tiny, knew they needed some proactive muscle to succeed in their jobs, and in 1973 they set about building it.

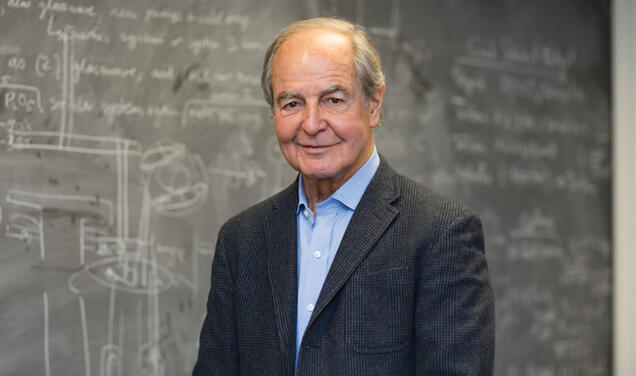

Having assessed its binary image problem accurately, the new Bowen administration took a two-pronged approach to a solution: For the alumni, there was the warm and fuzzy Fred Fox ’39 reassurance captured in the 1974 film At Princeton: A Walk in the Springtime that we reviewed a couple years back. But first, University officials felt called upon to confront the preppy stereotype with a production that showed the seriousness and sophistication of the new multilayered Princeton. Spearheaded by development director Gerald Patrick, they showed their seriousness by digging up two young, independent award-winning filmmakers and letting them have at it. Julian Krainin and DeWitt Sage were among the early wave of naturalist documentary filmmakers in the wake of Frederick Wiseman’s revolutionary Titicut Follies of 1967, an abrupt and disturbing look at a mental hospital in Massachusetts, fastidiously edited and presented without narration, which remains legendary. They had cut their teeth on a similar stark documentary for TV, The Other Americans, detailing the brutality and despair of the life of the poor, then the contrasting Art Is…, nominated for a documentary Academy Award in 1972, featuring Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins. After months of research on campus, Krainin and Sage crafted a 30-minute film treating the target applicants as grownups – abrupt cuts, intense moods, challenging ideas with no context, no narration of any kind – and featuring a microcosm of great minds at work. Among others, the magnificent physicist John Wheeler, his younger compatriot Aaron Lemonick *54 (who had risen to dean of the faculty), Shakespeare authority/actor Dan Seltzer ’54, and a startlingly young (39 years old during filming) President Bill Bowen *58, lecture, run precepts, converse with alumni and students, and – implicitly but very decidedly – build a pointillist portrait of a philosophy of undergraduate education. Here’s how it looks: https://youtu.be/sfFo2m9gR9k

Apart from the highly crafted verbal message, the images of campus, and au courant mood-music treatments – the opening resembles the abstract reflective interludes in Kubrick’s great 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1968 and a later passage is a Scott Joplin rag straight from The Sting, which was still in theaters – the film is so successful that you essentially can taste Princeton (or at least, how the on-screen players wished it to become), and grasp the intellectual argument for a liberal-arts education: namely, learning howto learn and learning what there is remaining to be learned is far more important than what you learn. In slightly different words, it’s an identical case to that being made, increasingly desperately in the vocational-fixated world of today. At the time, though, the effect was stark if not disorienting.

Which, oddly, was just what the mainstream Motion Picture Academy needed; the Hollywood community was deeply conflicted over the cultural changes of the ’60s. At the 1969 Oscars, 2001: A Space Odyssey wasn’t even nominated for best picture, but in 1970 the voters anointed the X-rated Midnight Cowboy and created gigantic buzz – and the largest Oscar-telecast audience ever. Michael Wadleigh’s great Woodstock won best documentary the year following, but the academy stumbled by not nominating it for best picture; M*A*S*H and Five Easy Pieces were nominated, but lost to traditional biopic Patton. As the fight between classic Hollywood and the young experimenters raged, 1974 presented a problem: Everyone knew The Sting, the beautifully crafted reprise of the Newman/Redford/Hill team from Butch Cassidy, was set to dominate the awards; even a sensation like American Graffiti (five major nominations, zero wins) got crushed in the stampede. Apparently in reaction, the panels nominating short films chose seven wacko (not a technical term, if you were wondering), highly stylized films; Princeton: A Search for Answers arguably was the most accessible despite its modern style; it was promoted by the Hollywood-savvy Logan, among others, and Krainin and Sage and Princeton had themselves an Oscar for best short documentary.

This had some truly odd aspects. In the ensuing 40 years, no college PR piece has even been nominated. Meanwhile, the Prince disliked its emphasis on the sciences (ironic now, eh what?), and as Helen van Rossum’s outstanding Reel Mudd blog posting on the film notes, traveling admission officers had to present it at the end of promotion sessions because its intellectual starkness tended to intimidate the very students it was trying to attract. (Was the prospective Class of ’78 talking rebellion but really conformist? Great topic for another day.)

Princeton: A Search for Answers did have staying power. The need for a new recruiting film didn’t gel for 17 years, and Princeton: Conversations that Matter (1991) turned out to be almost a half-hour reboot of the 1973 Oscar-winner – but with a restrained narration, which lessens the urgency and impact of the professors’ ideas, but might reduce the panic of high school viewers.

The subsequent elegant, massive (two hours, precisely the length of Citizen Kane) 1996 production for the University’s 250th anniversary, Gerardo Puglia’s Princeton: Images of a University, seemed to fulfill the need for subsequent fresh PR material, although it is overwhelmingly a history piece, not really aimed at applicants. And by the time that wore a bit thin, the Web was in full swing; such crafted features now have been broadly supplanted in the new marketing mix by a huge pile of five- to eight-minute video pieces focused on various single facets of the diamond-like existence of Princeton.

So now that everybody can make their own selfies by the thousand, it’s finally time to build the Lewis School to help out (maybe by convincing us that one good portrait is worth a thousand flickrs). And while we’re at it, a tribute to Oscar-winners Krainin, Sage, Stewart, and Ferrer might be appropriate, if only to screen and critique all those short feature pieces destined for the high schoolers of the iPhone era. We could call it Short Attention Span Theater.

No responses yet