Recent Past Comes Alive in John Foster Dulles ’08 ‘Oral History’

Editor’s note: This story from 1967 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

Richard D. Challener, Professor of History at Princeton, entered the University with the class of ’44, graduated in ’47 with highest honors after military service. He earned his Ph.D. at Columbia. For several years he was Associate Dean of the College at Princeton, returned to full-time teaching last fall. His books include The French Theory of the Nation in Arms: 1866-1939; and The National Security in the Nuclear Age, ed. With G. B. Turner. He has just completed Admirals, Generals, and American Foreign Policy: 1898-1914. He has conducted many of the Dulles Oral History interviews.

John M. Fenton, A.B. Wesleyan University, is Associate Director of Princeton’s Office of Public Information. He is a former Editor of the Gallup Poll and the author of In Your Opinion (Little, Brown, 1960), a pollster’s look at post-war America. His articles for University, based on multiple interviews with Princeton faculty members, include “When Southern Negroes Get the Vote” and “Insights into Red China.”

That’s a complete distortion of fact! Matter of fact, the man knew nothing about it. How did he know what my relations were? Matter of fact, I admired Dulles from the very beginning for two reasons. One, his obvious sincerity and dedication to the problems that were put before him, and secondly, the orderliness of his mind. He had a little habit before he started to talk – probably in his youth he may have had a little bit of stammering – he waited, sometimes it would be three of four seconds, before he’d start to talk. But when he did it was almost like a printed page; he had a very orderly mind.

That observation by Dwight D. Eisenhower is from his contribution to Princeton’s John Foster Dulles Oral History Project, the former President having been asked to comment on the assertion in Emmet Hughes’ book, The Ordeal of Power, that his (Eisenhower’s) first reaction to Dulles had been impatience and boredom. The page of the transcript seems to crackle with Eisenhower’s responses; the reader can almost hear the familiar voice and syntax. (Other transcripts, as will be noted, tend to support Hughes, Princeton ’41, in his view of the early Eisenhower-Dulles relationship.)

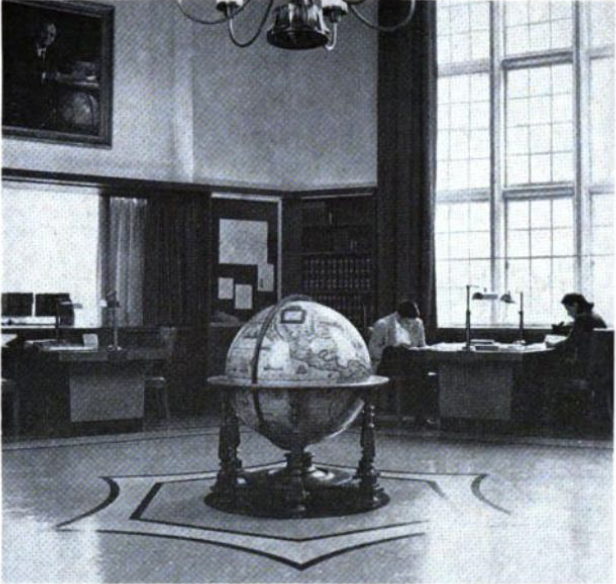

Since the spring of 1964 representatives of the Oral History Project have interviewed almost 300 individuals int his country and abroad – chiefs of state, foreign ministers, senators, congressmen, members of the Eisenhower Cabinet and the Department of State, former law partners and sailing companions of Dulles, officials of the World Council of Churches, members of the Washington press corps, and family and personal friends – and tape-recorded their recollections and reminiscences of John Foster Dulles. The project is now virtually complete; nearly 200 interviews have already been transcribed from their tapes and, in typescript form, are on deposit in the Princeton University Library, the vast majority of them available to scholars and historians. They are not open to the general public except with special authorization from the University Librarian, William S. Dix.

The transcripts bring vividly to life nearly every phase of Dulles’ long, distinguished and varied career, including his youth in a Watertown, N.Y., parsonage, undergraduate days at Princeton, highly successful law career at Sullivan & Cromwell, his role as prominent lay spokesman for the Protestant churches in World War II, as Gov. Thomas E. Dewey’s principal adviser on foreign policy, as participant in the establishment and early operations of the United Nations, his responsibility, as Republican consultant to the Truman administration, for the negotiations of the Japanese Peace Treaty; and finally, the culmination of his public service as Secretary of State from January 1953 until his death in May 1959.

The purpose of the project has been to augment the 20th century archives now held by the Princeton University Library (which include the personal files and papers of Secretary Dulles) and to assemble source materials enabling future scholars to write more informed histories of these decades. The entire “oral history” concept is relatively new (having been made possible by the portable tape recorder and, to an extent, jet plane access to farflung sources), and has created a different type of archive: transcripts of the spoken words of those personally involved in the historical process.

The Dulles Oral History Project had its inception in 1963 in conversations between the Librarian of Princeton University and John W. Hanes Jr. and Roderic L. O’Connor, both former Special Assistants to the Secretary of State when John Foster Dulles held that office. Both had been active in the complex negotiations which led to the presentation to the Princeton University Library of Secretary Dulles’ personal papers and the deposit there of microfilm copies of some 100,000 documents from the official files of the Department of State; and both men had been involved also in the gift to Princeton by a group of the Secretary’s admirers of the John Foster Dulles Library of Diplomatic History, a new wing to the Firestone Library building. The idea of interviewing those who had known the Secretary, in private or public life, and of recording and preserving their recollections, seemed a logical supplement to the written record. Preliminary plans were made, and the project became a certainty when the Rockefeller Foundation made an initial grant, later supplemented by another grant and by substantial gifts from interested individuals.

For policy guidance and assistance in arranging interviews a distinguished advisory committee was formed, composed of diplomatic associates of the Secretary and scholars from Princeton and other universities, under the chairmanship of former Ambassador Hugh S. Cumming Jr.

Interviewing began when Dr. Philip A. Crowl, former Princeton history professor, who had earlier joined the Library staff for a time to work with Secretary Dulles in selecting and organizing the microfilmed official documents in the Dulles Papers, took a six-month leave from the State Department to become Director of the new project. When he returned to Washington, Mrs. Bertie Miller became Executive Secretary, with Dr. Crowl continuing as an active consultant.

– William S. Dix

Librarian, Princeton University

It is, to be sure, a type of archive which professional historians find less satisfactory than official documents and correspondence, for human memory is frail, and those interviewed may embellish, or speak less than candidly. So oral history transcripts must be used with caution.

But oral history transcripts are a valuable supplement to traditional sources. For example: The writer of contemporary history suffers not from a lack, but an excess, of materials. Not only have government agencies increased in size, with an astronomical increase in paper output, but the historian of American foreign policy, for example, can no longer, as he did in pre-Pearl Harbor days, rely largely on the formal records of the State Department. As foreign policy has grown more complex, decision-making has either shifted to or been shared with other agencies, many of which did not exist before; or which, in the past, had little involvement in foreign affairs – the military services, the Defense Department, CIA, National Security Council, UN, even the Treasury and Agriculture Departments.

What the recorded reminiscences offer, quite simply, are guidelines, clues, possible hypotheses for dealing with this ocean of material. Oral history does not produce the “hard fact,” but the opportunity to understand, for example, how the working relationship between Allen’s CIA and Foster’s State Department was subtly affected, in a way that no “formal” document could show and no organizational chart reveal, by the fact that the men were brothers. Or it offers, by recording the recollections of a long-time member of the House of Representatives, a chance to compare the differences in the way Dean Acheson and Dulles treated – and were treated by – the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

Moreover, some of that ocean of contemporary documentation is either wholly or partially closed to the historian by regulations presumably made in the name of “security.” Item: the 100,000 microfilmed documents from State Department files that form the bulk of the Dulles Papers in the Princeton University Library are, for security reasons, just as tightly restricted as if they were still in the State Department of the National Archives. Thus, as Herbert Feis eloquently said in a recent issue of Foreign Affairs, today’s “shackled historian” must frequently do battle to get officialdom to remove classification stamps from a bewildering array of government documents. In coping with this problem, the transcripts of oral history, however imperfect or tantalizingly incomplete, can provide a starting point for the contemporary historian. As Dr. Philip Crowl, director of the Dulles Project, has observed in the current issue of the American Historical Association Newsletter:

Insights into a man’s character, explanations of his behavior, opinions about him based on close association, this is the essence of oral history. Not the proven fact, but the informed guess, is its finest product. Oral history will seldom furnish the last word on any subject; it will, however, often produce the first.

For the student of John Foster Dulles, the transcripts now assembled at Princeton offer not only insights but also biographical facts for which there is no source. Many transcripts bear upon the all-important decision-making process in the State Department; how and under what circumstances Dulles and his associates formulated and conducted American foreign policy. And there also is a great store of information about major administration policies – from the famous “unleashing” of Chiang Kai-Shek to the intervention in Lebanon, from the concept of “liberating” captive peoples to “massive retaliation,” from Quemoy and Matsu to Suez and Vietnam.

Moreover, because of the wide range of the interviews, many transcripts deal with broad aspects of American foreign policy other than those directly associated with the Dulles era in the State Department: the role of the Protestant churches during World War II in their concern for the shape of the post-war world, the evolution of the UN, to cite but two. Similarly, transcripts deal with recent issues that were national in scope and not simply foreign policy questions: “McCarthyism,” for example, and the difference between Eisenhower’s national security apparatus and that of Kennedy and Johnson.

The interviews clearly indicate that Dulles was a man of many dimensions, a complex personality, not, as he sometimes seemed on TV screens and the nation’s front pages, two-dimensional remote austere dedicated solely to the compelling issues of the cold war. They show him, for example, as churchman, lawyer, and student of the Wilson era.

Dulles was once likened by Eisenhower to an “Old Testament Prophet,” and by certain members of the Washington press corps he was less reverently termed a “card-carrying Christian.” Even Roscoe Drummond, Washington columnist and Dulles’ sympathetic biographer, recalled in his interview that “there was a general feeling in Washington – and quite a general feeling among foreign diplomats – that Foster Dulles wrapped his temporal views in theological clothes in a way which made him appear smug and moralistic.” And Robert Murphy, Deputy Under Secretary of State, lightly recalled an incident, during one State Department meeting, when a participant’s reference to the Bible cause Dulles to wave a finger and interject, “I want it understood that I know more about the Bible than anybody else in this room.”

Actually, he had been deeply influenced by religion since boyhood days in Watertown, where his father was a Presbyterian minister. His sister, Mrs. Deane Edwards, in her interview, told how they memorized portions of the Bible together when they were children and how the five Dulles children went to church each Sunday armed with pencils and notebooks. “It was a very serious business. We felt that we were reporters on our father’s sermon.” Then, at Sunday dinner, there would be a discussion of it. Mrs. Edwards recalled that when Foster began to consider a career as lawyer rather than minister, “he felt drawn to the opportunity, which he really felt hadn’t been explored, of being a Christian lawyer.” Similarly, Raymond B. Fosdick, President of the Rockefeller Foundation when Dulles was a member of its Board, remembered that the future Secretary had urged the Foundation to give attention to religious projects at a time when few other of its other trustees had such interests.

It was, in fact, through the Protestant churches that Dulles was drawn actively into foreign affairs. By the ’30’s, as senior partner in Sullivan & Cromwell, he had long been involved in international litigations – the famous Kreuger and Toll case, for example – and his conversations had always revealed deep interest in international affairs, and particularly his disenchantment with many aspects of the Versailles settlement. His law partner, Eustace Seligman, recalled that Dulles had always believed that the reparations settlement had placed an unfair burden upon Germany. Then, in 1937, at the urging of Dr. Roswell Barnes, his family minister, and one of the leaders in the movement that created the World Council of Churches, Dulles attended a series of meetings at Oxford – a gathering which, in the testimony of Samuel Cavert, onetime General Secretary of the National Council of Churches, was devoted to the idea that “the churches of the different nations have a basic spiritual unity that transcends their national relationships.” Dulles was in a group whose purpose was to examine the conditions necessary for peaceful change in the international community.

Many interviews, with churchmen as well as member of his immediate family, testify to the impact of the Oxford meeting on Dulles. As Cavert recalled, “He felt a spirit at Oxford which was at a deeper level than national self-interest and without which he felt that the political and other approaches would inevitably in the end be feeble;” that the churches had great potential for creating the conditions necessary for a durable international order and that it was his duty, as a Christian, to be active in that work. Soon he was deeply involved. “I think all of us used to marvel at his willingness to give so much time. He was, of course, an exceedingly busy lawyer…But, literally, any time Walter Van Kirk, or Roswell Barnes or I…could telephone him and go down and see him on a few hours’ notice, and he was quite prepared to spend an unconscionable amount of time attending conferences, which are awfully time-consuming. It sounds a little overly pious maybe – but I think he really had a sense of Christian vocation about this.”

At the outset of World War II, the Protestant churches created a Commission on a Just and Durable Peace, to give expression to the post-war goals and hopes of American Protestantism. Dulles was chairman of the commission, which included Reinhold Niebuhr, John Coleman Bennett (now President of Union Theological Seminary), and Henry Van Dusen, as well as many other leading Protestants of widely divergent views, including pacifism. As chairman, Dulles became the lay spokesman for the aspirations of the Federal Council of Churches in world affairs. It was, in fact as well as in theory, his commission; his mark was on all of its documents, most notably its principal one, The Six Pillars of Peace, a call for a broad, liberal and international American role in the postwar world.

Richard Fagley, now Executive Secretary of the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs, recalled in his interview that Dulles “wanted policies that were realistic” and that “he had a great deal of concern for a postwar settlement that was not vindictive, but would provide some basis for reconciliation.” As Fagley remembered his work with Dulles, “He really enjoyed looking forward to setting out goals which were grounded in real possibilities, but pointed toward something more creative and curative. In fact, those were two of his favorite words – creative and curative…Those were two words we always associated with him.”

And John Coleman Bennett testified that the churchmen who worked with Dulles were proud of him, regarding him as “a big figure who had – I think, quite in a disinterested way – come to identify himself with the churches, and I think he made this for a time perhaps his major interest.” Similarly, O. Frederick Nolde, Associate Secretary General of the World Council, said, “There was a very considerable meeting of minds in the arena of world affairs because what Dulles was after at that time was revolutionary,” – an attempt to draw the U.S. away from the isolationism that had rejected Wilson’s League of Nations and towards participation in the U.N. “The commission had an affirmative, a constructive bent that was given substance and leadership by Dulles because he had the know-how.”

Bennett, who later became a critic of Dulles as Secretary of State, also emphasized that during the war and for some years afterward there was “mutual respect between him and the churchmen who worked with him.” Also, he believed Dulles “was really the creative leader.”

He was the leader of this effort for about a decade. He was, in dealing with church groups, open, and he listened. He was not dominating in an objectionable sense. He always did his homework, he always had drafts, he always knew the line he wanted to take.”…He had a line, but he was quite open…it was a rather empirical movement toward world order that rejected shortcuts, like world state – and, of course, he rejected all pacifist shortcuts. He rejected the world government shortcuts. I’ve always said that I thought it’s very interesting that the American churches never went in heavily for world government, because of the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr and John Foster Dulles – Niebuhr providing, perhaps, the broader rationale, but Dulles also having this intuitive sense of the way things developed, that they didn’t develop by fiat.

Along with the Protestant leadership, Dulles disliked the original plans for the U.N. drawn up at Dumbarton Oaks in the winter of 1944-45, and he was influential in the mobilization of the American church movement for the cause actually accomplished at San Francisco – the broadening of the U.N. charter to enlarge the role of the General Assembly and prevent the U.N. from being, as Roosevelt had once preferred, simply a continuation of the wartime alliance. At San Francisco, though Dulles as an adviser to the American delegation had no formal or official ties with the churchmen present, he kept in touch with his friends. Dr. Nolde recalled:

I remember…it must have been in the Opera House where the opening meeting was held…There had been some who said it should be opened with a prayer. Dulles had discussed this with some of us. I, myself, opposed it. I said, “Prayer in whose name? What form of prayer?” Then, when Stettinius was going to open the meeting, and a few of us were sitting all the way back in a place reserved for us, Dulles came back just before the opening of the meeting and said, “We have found the answer. The Secretary of State is going to call for a moment of silence for prayer or meditation.”…He’d come all the way down the aisle of the Opera House, as people were coming in and delegates were taking their places, to tell us this…

It is clear that Dulles’ outlook in world affairs, then as well as later, was influenced by his religious background and interests. Samuel Cavert recalled that at the opening meeting of the World Council of Churches in Amsterdam in 1948 Dulles had a dramatic confrontation with a Czech professor over the attitudes that a Christian should take toward Communism. Dulles, as Cavert remembered his speech, emphasized that the Christian regarded moral law as superior to man-made law and stressed the sanctity of each individual as a free spirit. Since Communism did not recognize these two fundamental principles, Dulles held that it regarded violence as inevitable. Similarly, Gen. Lucius Clay, who was Military Governor of Germany and Commander of American forces in Europe, believed that the basis of Dulles’ distrust of the Russians was religious: “I certainly got from my talks with him that where there was no religion in a country, the trustworthiness and stability of that country were certainly questionable.”

The various interviews with churchmen, which, incidentally, illuminate an aspect of Dulles which has only been lightly touched upon by his biographers, also provide an interesting perspective on his work as Secretary of State. Of the churchmen who worked with Dulles in the 1940’s, many grew cool toward him as a policy-maker in the 1950’s. “They wondered,” said Cavert, “whether he had changed his position…or whether they had really understood him before.” Among the transcripts on this point, none is more poignant than that of Ernest Gross, a former American representative to the U.N., and like Dulles before him, an important lay member of the National Council of Churches. In 1958, Gross recalled, Dulles was invited to speak before the World Order Study Council at its meeting in Cleveland. Before the speech there was a reunion of his old friends at a dinner, and reminiscences were exchanged; it was a genuine recapturing of their friendship and camaraderie. Dulles then gave his speech, coming out strongly against admitting Red China to the U.N. After Dulles had left for Washington, a majority of the several hundred delegates endorsed a report looking favorably toward China’s admittance. Gross recalled:

It was strong and bitter medicine to Mr. Dulles because word came back almost at once to us that he really felt it a personal blow and a repudiation. He had come to Cleveland, he had made his views clear in accordance with his own lights, and this was really – well, to put it mildly from his point of view – a most unfortunate, if not a deplorable aftermath.

The transcripts draw attention to Dulles’ legal, as well as his religious background, and to the way he brought his legal training to bear upon problems of foreign policy. Robert Bowie, who headed the Policy Planning Staff in Dulles’ State Department, called attention to the Secretary’s “superb capacity as an advocate,” while Ernest Gross, commentating on the skill that Dulles demonstrated in U.N. debates, described his presentations as “built on legal analysis, and the legal method, and he excelled in this.” Lt. Gen. Andrew Goodpaster, who was Staff Assistant to President Eisenhower, also commented on Dulles’ “tremendous skill as an advocate,” and remembered telling the President on several occasions, after both had listened to a presentation by the Secretary, that “if you would give Mr. Dulles two or three premises from which to start, you wouldn’t stop him before he got to his conclusion. Once you had done that, he would carry you all the way.” And Goodpaster recalled that Dulles clearly enjoyed playing the advocate’s role. “One day he came into the Cabinet room, he had a very tough proposition to put across, and I think he expected his main adversary to be George Humphrey. He had formulated this with great care, and he started building his case, probably on the subject of foreign aid.” Dulles had completed his first paragraph and a few sentences of his second, Goodpaster noted:

…you could just see him organizing this – when Mr. Humphrey said something to this effect, “Foster, if I understand your case, you’re arguing for thus and such foreign aid?”

And Dulles said, “Yes, I surely am.”

Mr. Humphrey said, “Well, I agree with you.”

And you could sense the disappointment in Mr. Dulles that he was not going to get to use this great argument, but he had sufficient discipline and power to laugh and say, “Well, one thing I learned as a lawyer…when you’ve won your case stop talking!”

Others, less favorably disposed to the legal method, were critical. Arthur Krock, for years Washington columnist of the New York Times, found “a certain trickiness” in the legal side of the Secretary’s performances, and added that this was something that “is not only tolerated but rather expected in the law.” CBS correspondent David Schoenbrun, whose attitude mirrored that of the critical segment of the press, suggested that “the man tried not to lie, but, you know, lawyers can manage not to lie in the most lying way I’ve ever seen. And he was a master of the non-lying lie.” Robert Murphy suggested the Secretary’s legal background might help to explain why he ran the State Department as he did, since a lawyer will approach an administrative structure differently from a man whose roots are in a more hierarchically or vertically organized profession or business. “He had his own system,” Murphy related, “I always thought it was the case of a lawyer who is an individual worker, rather than an organization man, and the matter of delegation of functions and duties was sometimes difficult for him, because he undertook so much himself.”

Many historians will be interested also in those transcripts that show how Dulles, like FDR before him, vividly recalled the Woodrow Wilson years and sought to avoid repeating Wilson’s presumed errors. Certainly Dulles’ pride in the Japanese Peace Treaty was related to his conviction that it was “curative” rather than vindictive, as he felt Versailles had been. Dulles’ uncles, Robert Lansing, had been Wilson’s Secretary of State, so there was family experience for Dulles to draw on, and to inspire his well-known reluctance to permit any individual to come between himself and President Eisenhower, as others had come between Wilson and Lansing.

The problems of Wilson’s illness in 1919 were clearly on Dulles’ mind at the time of Eisenhower’s heart attack in September, 1955. As Richard Nixon remembered:

Basically. There had to be at that time, men on whom I could rely…Dulles was one – he was first…but Dulles was the man who – because of the accident that he had been through it before with his uncle – Dulles was the man who advised and guided me…And he was also the one that urged Sherman Adams go out to Denver so that we would not have the Wilson experience of just Mrs. Eisenhower and a press secretary out there. He specifically said that at the time…[Moreover, Dulles] urged that Cabinet meetings be held, and that Security Council meetings be held, and that the President write me a note – in fact, I would say that Dulles was really the general above anybody else at that point. Others contributed to what we ought to do, but we never did anything in that period without checking with Dulles.

The oral histories contain much information about Dulles’ relations with the press, a vital subject since the public knew Dulles mainly from the newspapers and magazines and the Secretary was deeply concerned about communicating with the people.

The press corps, as noted, contained some astringent critics. James Shepley, who as head of Life’s Washington bureau wrote the controversial “brinksmanship” article, recalled in his interview that Dulles, who had enjoyed the high regard of the Washington press during the years he was adviser to Secretary Acheson’s State Department, lost some of it when he became Secretary himself. Said Shepley:

The honeymoon between the Eisenhower administration and the Washington press corps was the shortest on record. The whole Eisenhower administration alienated the Washington press corps in about thirty days…They came breezing into Washington as though on some heaven-sent mission to clean up the town, and end all that corruption, and Korea, and Communism…And Dulles sort of got caught up in that net – mine, too – although he maintained the respect of the press corps to the end. He had enough intellectual attractions, he was sufficiently in command of his subject, that the Washington press corps was never able to acquire any contempt for him.

Nevertheless, in Shepley’s judgment, Washington reporters were “quick to side with (the) view that he was a moralizer, and that a lot of his phraseology – like ‘massive retaliation’ – created more problems than they solved.” Dulles went “from being one of the fair-haired boys of the press corps to being just another Secretary of State having problems.”

Other newsmen suggested that the press often regarded him as devious and that, despite his sincere interest in providing public information, he “used” them for his own purposes. But Roscoe Drummond, who as Herald-Tribune columnist was close to the centers of Republican power, observed, “Now, every newspaperman was aware, too, that Mr. Dulles always thought through how he wanted to use his press conference. And it was up to newspapermen to think through how they wanted to use Mr. Dulles. It was a mutual challenge in a sense. But he used the press conference as few Secretaries of State have used the press conference – as an instrument of diplomacy and an instrument of advocacy.” And, reflecting on the years that have passed since the Secretary’s death, Drummond expressed his belief that most correspondents covering the State Department found that Secretary Dulles’ press conferences “were the most outgiving, the most informative, the most meaty that we had ever had up to that point or probably ever since.”

The transcripts provide insight into one highly controversial press relationship – the famous “brinksmanship” article in a January 1956 issue of Life, whose cover bore the provocative headline “Three Times to the Brink of War: How Dulles Gambled and Won.” Some weeks earlier Charles Murphy, a Fortune writer, seeking background material for an article on economics and foreign policy, had arranged a Sunday interview in Dulles’ home. But when the session was held, three men were actually present – Murphy, Shepley, and Jack Beal, then at work on a biography of Dulles, now Time bureau chief in Ottawa. Beal, in the interest of his book, tape-recorded the discussion; and Shepley, who had come as an observer, was so intrigued by Dulles’ comments that he decided to write a piece for Life based largely on Beal’s recording. When Shepley’s articles appeared – with its “to the brink” coverline – a furor arose, for the implication was that Dulles had deliberately taken the U.S., on three separate occasions, to the brink of war as a technique of diplomacy. Overnight, some branded Dulles as a “brinksman” who enjoyed waving atomic weapons while teetering on the abyss on nuclear war.

Why did Life’s article give that impression? To some extent it was because Dulles characteristically tried so hard to communicate his ideas to an unsophisticated public that the effort sometimes backfired. Commenting on this, Robert Bowie recalled that “in speaking he was so anxious to get things simple and clear and forceful and to have them get attention that he gave the picture of a mind which had all of these qualities – of simplification in black and white.” Bowie pointed to “certain oversimplifications in his speeches. He had a tendency to present them this way which gave an impression about his own thinking that was misleading. I think that anybody who read any of his speeches and was something of an expert always felt that they were oversimplified or set too clear, too simple, and therefore tended to assume that Dulles himself was equally simple-minded or narrow or limited in his conceptions or considerations.” Similarly Roscoe Drummond, recalling his own conversations with Eisenhower about Dulles, said that the President had observed only two weaknesses in his Secretary of State, both minor and matters of exposition, not of substance: “either to over-simply or to over-dramatize.”

Thus, the quotes and phrases of the “brinksmanship” article were actually in the transcript – for example, the provocative phrase (referring to Eisenhower’s reaction to one crisis) “he came up taut.” Trying to make crystal clear his belief that the U.S. could not surrender to Communist threats, Dulles had been too explicit. Henry Luce, published of Time and Life, recalled that, immediately after publication of the article, he and his associates decided to make a clarifying statement: “I just felt that here was a situation in which he (Dulles) was under very heavy attack for which he really oughtn’t particularly to take the blame.” The reason he felt this way, Luce went on, was because

Shepley’s main mistake was putting something in quotation marks which should not have been put in quotation marks – in which he would have been permitted to give the sense of the thing. And the sense of the thing was that in very tense world affairs there are times when you have to be willing to go to the brink of war…Dulles had put this a little dramatically in saying, “going to the brink.” I forget what my statement was, but it seemed to me so clearly that I had to help as far as I could to take Dulles off the hook, because this was not his use of the word “brink” – however much sense it makes…it was not to be used in quotation marks.

The difficulty was compounded by various rewritings and shortenings of Shepley’s lengthy original piece, and by subheads, as well as the coverline, all adding to its provocativeness. Shepley agreed that “we” – meaning the Time-Life organization – “had committed the sin of over sensationalizing what he had said…over sensationalized it with the cover and headlines,” and in consequence Dulles “appeared to be bragging about taking the country to the brink of war – which, of course, wasn’t what he was doing at all…It was compressed further beyond my original draft, which is frequently what happens in the process of editing. Things become sharper and less subject to further explanation…If I had it to do over, I’d have been much more concerned about such things as headlining and billing…There’s no point in drawing fire to a proposition, and we did draw unnecessary fire.”

Shepley read into his interview a portion of a transcript of the original tape recording in which Dulles was clearly trying to argue the point that a nation, under pressure from a remorseless opponent, cannot afford to indicate in advance that it will give in or surrender; that to do so might create a greater danger of war. Life did not make clear the full implications of the following excerpt from the Dulles tape:

This time we’re going on the theory – it is really the theory which underlines the North Atlantic treaty, as it was conceived by Senator Vandenberg and myself – the best insurance against war is to be ready, able, and willing to fight. It is extremely difficult to hold that position without leading some of our friends and allies to think that you are truculent and want to have a fight. It is very difficult also, to have this readiness to fight, in terms of your military establishment – the morale of your people, your military people, without there being among them a few who are going to talk as though they wanted to have a fight. And I think that tended to frighten people a good deal in the beginning. But as they worked with us, and certainly this year, I think there has come about a general acceptance of this view, of those policies that we are following – that they are really policies which we genuinely believe will lead to peace and not to war…

[It] is a very delicate operation, to make the enemy or the potential enemy realize that you are ready and able to fight, if need be, but he can’t assume that you are going to retreat and fall back – appease. You can’t do that without taking a certain amount of risk. Now we’ve taken a certain amount of risk, as I’ve said, and they’ve been extremely calculated risks which were designed to avoid any implications that we were frightened or ready to surrender and fall back. It seems that these have been calculated avoid opening up what might be called a general war with China, which in turn could readily become a general war throughout the world.

So much for Dulles as brinksman.

The aspiring biographer of Dulles will find many transcripts which bear upon the man, his ideas and his outlook – for example, on the question of whether throughout his career he consciously sought to become the Secretary of State – an ambition inferred by many who knew him, or thought they did. But more than a few of the recorded reminiscences throw doubt on this.

His law partner, Eustace Seligman, recollected a meeting in Dulles’ office at Sullivan & Cromwell in the spring of 1952 when it was evident that Eisenhower, if nominated and elected, might ask Dulles to become his Secretary of State:

Foster got another one of our partners in, Arthur Dean, and the three of us discussed it. And this is something that people I’ve told it to don’t believe. Foster said, “I don’t want to be Secretary of State.”…And the reason was he didn’t want the administrative detail. He didn’t want the political business of having to go up on the Hill to persuade people. He said, “The job I would like to have would be head of the planning group – to plan foreign policy and not have to worry about these other unimportant things.”

John McCloy, former American High Commissioner for Germany, who discussed the matter with Dulles after the November election, clearly recalled that Dulles wanted to be free to serve as general adviser to the President as well as that he disliked administrative detail. Or, as a newsman put it, he wanted to be “the prime creative instrument of foreign policy” while somebody else ran the Department. Likewise, and despite the Eisenhower remarks at the beginning of this article, several transcripts indicate that, while Emmet Hughes may have been harsh in his estimate of the beginning phases of the Eisenhower-Dulles relationship, others also felt it took six months or so for the two men to become fully confident of each other, and easy in their relations.

Robert Murphy recalled how, in the early months of the new administration, Bedell Smith could phone Eisenhower and, on the basis of their long years of familiar association, say, “‘Ike, I think you ought to do this,’ or ‘I think that’s a hell of a thing. Don’t do that.’” But then, Murphy continued, he would go into Dulles’ office and “Dulles would be on the phone to the President, and he’d be all deference and politeness, and ‘Mr. President’…and there was no informality there.” But Dulles, he noted, was assiduous “in his effort to adapt himself to the Eisenhower personality,” and “things worked out differently than people first expected.” Similarly, Roscoe Drummond, whose “inside” connections were particularly good, believed that Eisenhower was at first frustrated and annoyed by his Secretary’s deliberate, slow speech.

Glimpses of the off-duty Dulles, as well as colorful bits of personal and anecdotal information, emerge from many transcripts – material that will help to round out the human portrait. Mrs. John Elliott Jr. (then Miss Eleanor Thomas) was the Dulles’ social secretary and a longtime family friend. In her interview she sketches a warm, humorous, affectionate man – she called him “Cousin Foster” – a man “roaring with laughter” at himself as he hastily ran down the stairs of his Washington home to – belatedly – welcome the Crown Prince of Japan, and then laughing even harder as he raced back upstairs when he discovered that he had forgotten to put on his necktie. (The Secretary, having forgotten the impending visit, had hurriedly redressed after having put on his pajamas and gone to bed to read a detective story, one of his favorite pastimes.) He is also the man who need notes pinned in his closet to remind him “to put on a proper suit to go to meet the Queen of Greece” and the husband who told Mrs. Elliott that he liked his wife’s hair “when it all sort of bubbles up all over.”

A prankish quality was revealed in other interviews. Robert Purcell, New York executive and a personal friend, recalled that during a sailing trip on Lake Ontario in the late summer of 1958, the part – Dulles and three others – found themselves without salt. Dulles had neglected to buy it when he had gone ashore to buy the groceries in a tiny Canadian village. When they subsequently stopped at a small drawbridge, and went up to the Canadian bridge tender’s shack to register the vessel’s passage, the Secretary discovered a large salt cellar, full of salt. Assured by Purcell that “the coast was clear” with the bridgetender still down at the dock, Dulles dumped three-quarters of the salt on a piece of paper, folded it, stuck it in his pocket, then “sauntered innocently and nonchalantly back to the boat…so that we were once again supplied with salt.”

His secretary in the years before he was Secretary of State, Mrs. Doris Swartz, recalled that he “was a very demanding man – because he wanted perfection. He expected perfection. But in all the years I worked for him, he never yelled at me, as some of the other lawyers around the floor would do.” And she vividly remembered being present in Paris in November, 1948, when the unexpected news arrived that Dewey had conceded to Truman. “I was in the room at the time, and he never batted an eye. You couldn’t see one bit of disappointment or surprise or anything. He just said, ‘Thank you very much,’ and went right on with his business. Remarkable, I thought, because everyone knew that he wanted to be Secretary of State, and it was definite he would be if Dewey were elected.”

Robert Murphy remembered an incident not long after World War II when Dulles sought to renew his contacts with French political leaders. In 1947, when de Gaulle’s political star was in eclipse, Dulles was attending a Foreign Ministers Meeting in London as a member of the delegation. One Friday he told Secretary George Marshall that he thought he would run over to Paris for the weekend and renew his acquaintance with various French leaders.

He mentioned a few, Paul Reynaud and others. And then he said… “I might even be able to see General de Gaulle.” Well, several of us on the delegation were not so terribly impressed with General de Gaulle or his importance, and one of them was Bedell Smith, who was then our Ambassador to Moscow. And he said, “You might even be able to see General de Gaulle?... Hell, if you go over there and check into a second-class hotel, he’ll be calling for you in the morning.”

The Oral History project deals not only with Dulles the man but also with the way decisions, both crucial and routine, were reached in his State Department; with the daily routines of the Secretary’s office – who attended staff meetings, the order in which business was conducted, who was close to Dulles, how various functions and responsibilities were delegated. Two of his secretaries, for examples, described the basic office procedures in such a way that future researchers, going through a mass of documents, can tell easily which telegrams were actually read and signed by the Secretary – and which, as is standard Department practice, were simply sent out over his name by someone else.

It becomes clear that Dulles did not, as some have believed, “run everything himself.” Robert Murphy noted that “he was very considerate of staff, worked well with them. I think from the standpoint of staff meetings, there were probably more during his administration that we had ever had before.” Robert Bowie, too, called “totally wrong” the “common view that he more or less carried things around in his head and consulted with very few people…Basically he was not a man who was prepared to act by himself…He had strong views of his own on almost every subject, and he was normally quite prepared to express them. But in fact he wanted to test his thinking and be subjected to criticism and comment; and he always wanted to get ideas from at least a selected number of people in the Department.” Loftus Becker, who succeeded Herman Phleger as legal adviser, found that after a few months in the Department he reached an “ideal relationship” with Dulles.

Moreover, and again contrary to the popular image of the man, Becker recalled that Dulles liked to “sharpen his ideas by argument. He would stimulate you into contradicting him, and you would argue with him for half an hour on a point…where he did not attempt to overawe you by his position and experience. At the end of that time, sometimes to your great surprise, he would agree with you and withdraw from the position he had started out with.” Bowie added, “I can recall two or three times when Dulles privately complained to me of the fact that certain people in the Foreign Service weren’t forceful enough in expressing their views. He felt that they were too polite, too courteous, and that they weren’t willing to be vigorous enough in stating a difference of opinion.”

Bowie played this gadfly role himself, according to George S. Franklin Jr., Executive Director of the Council on Foreign Relations, whose oral history interview recalled an incident in 1954 when Dulles, at the request of Editor Hamilton Fish Armstrong, was reworking his “massive retaliation” speech into an article for Foreign Affairs. Dulles, Armstrong, and Bowie sat down one evening to make final revisions in the manuscript. Recalled Franklin:

Bob Bowie was very insistent on some points that he wanted Mr. Dulles to change, and it was getting late in the evening – when I say late, I mean something like one or one-fifteen, really late. Finally, Dulles got a bit annoyed with Bob after Bob had raised the same point about two or three times. And he said, “Well, damn it, Bob, can’t I even write my own article the way I want to myself?” And Bob’s reply was “Not until I’m damn sure you understand what my objection is.” And then, Bob left for home, and Ham stayed for a minute to say goodbye, and eh said, “You know, I hope you realize how lucky you are to have a fellow who will really stand up to you like that.” And Mr. Dulles said, “I certainly do, and that’s the reason I value him more than any of my other advisers.”

It has often been maintained that President Eisenhower simply delegated all responsibilities to his forceful Secretary of State. Many transcripts bear upon this widely misunderstood aspect of the Eisenhower-Dulles relationship that of General Goodpaster, among other, refutes the commonly held opinion that the President merely ratified the choices of his Secretary. “When we got to an issue which was really of profound significance to the security interests of the United States, he (Dulles) would quite regularly say to the President, ‘Mr. President, you’ve got to tell me what to do.’ He had no hesitation, when an issue reached what I would call basic or fundamental proportions in turning to the President in that way.” Goodpaster emphasized that the two men thoroughly understood one another, that Dulles knew the directions in which Eisenhower wanted to move, and the way his mind worked. Asked if there were differences of opinion between the two, or if Eisenhower ever “chafed” under Dulles’ advice, Goodpaster suggested that the President was always of a slightly more optimistic cast of mind, and on occasion would say to Dulles, “Well, I would be inclined to take a little more hopeful view than that.”

Richard Nixon was forceful in his appraisal of the manner in which Dulles reached his decisions. He was, the former Vice-President observed, a man of “high principle,” but also one who realized that standing on principle was not enough.

Now what I’m getting at is this. Let’s take the Quemoy-Matsu business. There were two incidents…over the space of four years, two crises, and in both cases, Dulles knew that the policy he was advocating was potentially unpopular. He used to talk to me about it. And there was no question, I think, as to what he was going to do ultimately. But he knew he could only do what he could get the public, the Congress, the Senate, his own party, and enough of the opposition party to support. And another thing, he knew that the worst thing he could do for the country would be to step out and get the President and himself to advocate a policy that the Congress, or particularly the Senate, would reject, or that public opinion in the United States would not support.

So, let me put it this way: Some political leaders in the decision-making process would put their finger in the air and say, “What do people want?” Dulles never believed in decision-making by Gallup Poll. Dulles, on the other hand, having decided what ought to be done, then wanted to check the Gallup Poll to see what was possible, and then he believed in educating the people and bringing them along to what ought to be done. He often said to me that that was the job of a statesman, never to find out what public opinion was. He said, “After all, you don’t take a Gallup Poll to find out what you ought to do in Nepal. Most people don’t know where Nepal is, let alone most Congressmen and Senators. But what you do is to determine what policy should be, and then, if there’s a controversy, and if there’s need for public understanding, you educate the public.”

Virtually every transcript touches upon great issues of national policy that were hotly debated during the years of the Eisenhower administration. “Massive retaliation” was one of the most controversial.

Dulles first described the concept – he did not use the phrase – in a speech before the Council on Foreign Relations in January 1954 to indicate the response that the United States could make to a hostile move by another power. It caused immediate headshaking. Henry Wriston, former President of Brown University, who sat next to Dulles on the night he delivered the speech, thought that the Secretary had made a great mistake and was especially disturbed that the speech showed “no sense of oneness with our allies.” Ernest Gross remembered that immediately after the talk, about a half-dozen of Dulles’ friends on the Council had a worried discussion. “And, really, we all expressed a sense of shock about that speech…We were startled – because we regarded (it) as…not very well guarded in terms of its presentation and analysis. …We all shook our heads and were really worried. We had a great foreboding about it.”

Other of the oral history transcripts make clear that the speech was an expression of declaratory, rather than actual, policy; that Dulles was never committed solely and exclusively to massive retaliation. “For example,” Bowie said, “I am quite sure that Dulles’ concepts, despite the deterrent strategy – despite the fact that he was the man who gave the ‘massive retaliation’ speech – assumed the capacity for more limited force. In private discussion he would always express the view that there must be the opportunity for flexible use of force, and not simply one choice.”

On the question of possible use of atomic weapons there is the testimony of George Humphrey and Herbert Hoover Jr. that, during his early months in office, Dulles had been particularly forceful in his denunciations of such weapons. Humphrey recalled early cabinet meetings at which Dulles spoke at length about the atomic bomb’s being “sacrilegious and that the Lord never intended such a thing, that humans shouldn’t have that destructive power – that it wasn’t right to use it.” According to these two men, it was a visit to SAC headquarter in Omaha in the fall of 1953 that changed Dulles’ mind and led him to accept America’s atomic arsenal as “a fact of life…It was here and here to stay.”

Such transcripts provide the historian of the Eisenhower administration with many leads for further exploration – the extent to which Dulles actually had a change of heart about atomic weaponry and its use; the degree to which he sought, within the cabinet and National Security Council, flexible and mobile retaliatory forces; the extent to which his original “massive retaliation” speech was misinterpreted.

The list could be extended almost indefinitely. There is Chiang Kaishek’s transcript in which the Generalissimo (speaking in Chinese, and with both Chinese and English versions available) says Dulles told him he favored a possible Nationalist return to the mainland, but put more emphasis upon the “political” aspect of a return than the military. And here is Eisenhower on the U-2:

The State Department, the Defense Department, and the CIA and ourselves – a very limited bunch – were in on this U-2 business. The habit was for this group to come to me to show why they needed a new reconnaissance program…We went through it repeatedly and I said “Well, boys, I believe the country needs this information and I’m going to approve it. But I’ll tell you one thing. Some day one of these machines is going to be caught, and we’re going to have a storm.” Foster always disagreed with me. He said, “The Russians will never make a protest.” He said, “We know that they know about these flights. They’re not going ever to admit that they were incapable of interfering with them, all these many months.” I said: “Foster, I just think you’re wrong.”

Gen. Charles Cabell, Deputy Director of the CIA, added that Dulles had to be persuaded anew about each U-2 mission: “Each time that we would lay a proposed mission in front of him, he was most interested in understanding the necessities for this and made it quite clear that unless he was convinced of the necessity for each operation, he would not approve it.” And, in view of Dulles’ general reluctance to endorse “summit meetings” with the Russians, there is also Eisenhower’s brief but revealing comment about the background to the 1955 Geneva meeting:

Well, both of us agreed that some deeds on the part of the Reds would have to show that there was some seriousness on their part. Any disagreement Dulles and I had on such a question would involved only some darn little detail. As for example, Foster said that the least we’ll take as evidence of Soviet sincerity in 1955, was the signing of the Austrian treaty. Well, suddenly the thing was signed one day, and he came in and he grinned rather ruefully, and he said, “Well, I think we’ve had it.”

On such policy issues, it should be emphasized, oral history produces few outright surprises. Newspapers, television and other communications media cover the American government so thoroughly that this country has few “state secrets” – at least not of the sort that a recorded interview is suddenly going to bring to light. But aspects of various policies are given new dimensions or put in different perspective.

For example, General Goodpaster’s transcript adds an interesting note on the American commitment of troops to Europe. Dulles always insisted on “the importance of our retaining significant forces on the continent of Europe,” and was consistently clear that “we had to maintain a real stake, a real commitment” there. Eisenhower, on the other had, believed that additional troops dispatched to Europe in 1951 had been sent only to meet the requirements of that particular, urgent period, and should later be reduced to no more than a division and a half. On this point, Goodpaster recorded this recollection:

Over the years when I was in the White House President Eisenhower would say, “I just don’t seem to be able to make any progress in getting those troops out of Europe. Our policy – the national policy established – is to cut those troops down.” And he said, “I’m going to issue an order to get those troops out of there.”

I said, “Mr. President, before you do that, I’d better tell you that it’s true that you have always had this in mind, but if you look at your policy documents, they do not call for removing those divisions from Europe.”

He said, “Well, that just can’t be. I don’t believe it. I don’t believe it. I won’t accept it.”

So I said, “All right sir. I’ll get the papers. I’ll have to show you.” And he said, “I don’t want to see the papers. I just don’t have any doubt in my mind at all.” And he said, “Foster Dulles is coming over this afternoon. I’ll check with him.”

I said, “Fine.”

So, in the afternoon, Mr. Dulles came over. We both went in the office. The first thing the President said was that I had been telling him that in spite of his view that these units were there just to cover a period of great danger, and it was our policy to bring them out, the established policy documents of the government didn’t provide for that. And he said, “Foster, I want you to tell him he’s wrong.”

And Mr. Dulles said, “Well, Mr. President, it isn’t as simple as that.” He said, “As a matter of fact, I’ll have to say he’s right.”

And the President said, “Say no more to me.”

But then they discussed it, and I’ll say this for Mr. Dulles – he held his ground on this. He felt very strongly that it would be damaging to our position in Europe, and to the stability and confidence that the Europeans felt, if there were such a withdrawal.

Many transcripts bear upon the Vietnamese question – and Dulles’ involvement in it. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, in his interview, noted that he had objected to sending American ground forces at the time of the French disasters in the spring of 1954, while Eisenhower related his astonishment at the French plan to garrison Dienbienphu: “As a soldier, I was horror-stricken…I said, ‘You boys are taking an awful chance. I don’t think anything of this scheme.’” After Dienbienphu’s fall, and the Geneva conference which led to the partition of Indo-China into today’s North and South Vietnam, Dulles was among the few – if not the first – to think that all was not lost to Communism there. General Goodpaster said:

On studying this over (Geneva), Mr. Dulles thought that it was perhaps not quite down the drain. Everyone else, I think, felt that it was…he felt that there might be something in this that would be worth trying to salvage, trying to sustain.

I recall his stopping by to talk with me and asking if there was any fairly senior military man that might be sent out there to assess the situation and see whether a viable military position could be created in South Vietnam. And I, in fact, suggested to him consideration of the man who was then sent, Gen. J. Lawton Collins, retired Army Chief of Staff.

But so far as I know, it was Mr. Dulles who came up with that. At least he brought it up to the President. The two of them talked it over. They thought that there might be some possibility in it, that it was at least worth giving it a try, rather than just write the thing off, which had been the disposition until that time.

When General Collins was asked about his recollections of what Dulles had said to him, he recalled “one of the statements that Mr. Dulles did make to me when I left Washington on my first trip down. He said, ‘Frankly, Collins, I think our chances of saving the situation there are not more than one in ten.’” The former Army Chief of Staff further recalled that, some months later, Dulles visited him in Saigon and was pleased with the progress of his mission. “And I think it was later, when I finally retired from the position at the end of six months, that he did say to me that at least we had increased our chances down there to something like fifty-fifty, rather than the ten-to-one he had first mentioned when I was sent down there in the first place. And he was very well pleased.”

There is, of course, abundant material on other aspects of the evolving Vietnamese situation. Still, much of it is nebulous. Anyone who reads the various transcripts in the oral history project may get the impression – or at least form an educated “hunch” – that perhaps, not long after the “heroics” of Dienbienphu, the Geneva conference and its immediate aftermath, South Vietnam ceased to be regarded as of highest priority. At least, a reading of the various transcripts would suggest that, if they are nebulous, it may well reflect the fact that after 1954 those involved did not regard Vietnam as a truly urgent question – thus the lack of vivid, detailed remembrances as there are of Suez, Lebanon, Quemoy, and Matsu.

This article is intended only to suggest the wealth of material in the Dulles Oral History Project. It cannot be definitive, even with respect to the project itself, for it has cited less than 40 of the nearly 300 persons interviewed. But it will fail if it does not convey some sense of the tremendous intellectual impact that John Foster Dulles had on those who knew and worked closely with him.

General Ridgway, who attended National Security Council meetings as the representative of the Army, was impressed with Dulles’ ability to range over the whole, complex international scene and “in the course of 15 or 20 minutes…brief the National Security Council without a note before him, in a most lucid manner, with beautiful continuity. It was a really marvelous display of intellect and memory and grasp of the whole situation.”

Richard Nixon described Dulles in Cabinet meetings:

What impressed his colleagues in the cabinet was his enormous knowledge of facts, his ability to present them in his very logical way, the fact that Dulles, for example, was quite deliberate in responding to questions, as all of us who knew him recall. He might wait a half minute or a minute before giving an answer to a question. He’d just sit and think, then he would answer. This was not a pose on his part, as it is in some cases, and it wasn’t because he didn’t know. It was simply that he was trying to refine his thoughts so that he could state them in a simple and convincing way. And that was immensely impressive to everybody.

Above all, he generated faith and reliance. The man who felt this most strongly was President Eisenhower:

Not only were our relations very close and cordial, but on top of that I always regarded him as an assistant and an associate with whom I could talk things out very easily, digging in all of their various facets and tangents and then – when finally a decision was made, I could count on him to execute them. …The man was possessed of a very strong faith in moral law. And because of this, he was constantly seeking what was right and what conforms to the principles of human behavior as we’d like to believe them and see them…Many people didn’t know it – but Foster possessed quite a delicious sense of humor and could laugh at himself and everybody else with great abandon. So that I came to lean on him very heavily because we came to be so close together…I not only liked the man – and I just hated to think of going on without his brain – but it’s one of those things fate brings along and you have to learn to live with.

This was originally published in the March 14, 1967 issue of PAW.

No responses yet