Reexamining the Legacy of Sigmund Freud

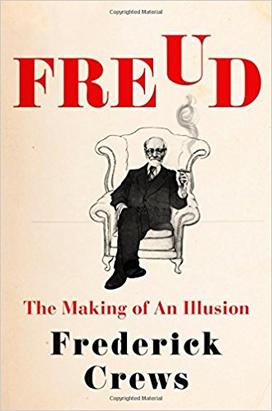

In his biographical study and slashing critique of Freud, Frederick Crews *58 aims to make Freud: The Making of an Illusion the last word on one of the most significant and simultaneously contested figures of the 20th century.

The author: Frederick Crews *58 earned his Ph.D. in literature at Princeton. He taught in the UC, Berkeley's English department for nearly 40 years. A 1970 Guggenheim fellow, Crews is also the author of The Tragedy of Manners: Moral Drama in the Later Novels of Henry James, E. M. Forster: The Perils of Humanism, and The Sins of the Fathers, a discussion of the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Opening paragraphs: “When Sigmund—né Schlomo Sigismund—Freud enrolled in the University of Vienna in 1873 at age seventeen, he bore with him the high expectations of a family that desperately needed him to become a salary earner. His father, Kallamon Jacob, formerly a wholesale wool merchant in Freiberg, Moravia, had gone bankrupt, and a year’s further search for business in Leipzig, Germany, had proved fruitless. Relocated in Vienna since 1860, Jacob had long since given up actively looking for work. The Freuds were surviving mainly on charity from local and distant relatives, including the two sons from Jacob’s first marriage, who had emigrated to England and become modestly successful shopkeepers in Manchester.

“If Sigismund had been the only child of Jacob and Amalie Freud, their future would have looked brighter, but the marriage was distressingly prolific in offspring. Although Jacob was already forty, with one or possibly two marriages already behind him, when he married the twenty-year-old Amalie, Sigismund’s birth proved to be the first of eight. And five of his siblings were sisters, unlikely to find middle-class employment or to make advantageous matches. Jacob was of no more financial help to his brood than Dickens’s Mr. Micawber, to whom his son would later compare him.”

Reviews: From Kirkus Reviews (Starred Review): “An elegant and relentless exposé . . . Impressively well-researched, powerfully written, and definitively damning. Crews wields his razor-sharp scalpel on Freud’s slavish followers, in particular, who did not want to see or who willfully redacted the sloppiness of Freud’s research methods in order to ‘idealize him.’”

1 Response

Norman Ravitch *62

8 Years AgoI am not qualified to judge...

I am not qualified to judge whether this fellow Crews, who has spent his whole life on a crusade against Freud, has anything valid to say. What I find interesting is that so many people, intelligent people, cannot accept Freud because his theories clash with their most intensely held prejudices, whether religious, moral, ethical, or even racial. I would suggest that all Freud haters seek Freudian analysis as quickly as possible!