Rewiring the brain

Susan Barry *81 explains the science that allowed her to see in 3-D

Susan (Feinstein) Barry *81 never understood why other children loved that classic American toy, the View-Master.

Not until a college neurobiology lesson on the development of the visual system did she realize that she lacked something most people take for granted: the ability to see in three dimensions. For her, objects did not occupy volumes of space but instead lined up in flat planes.

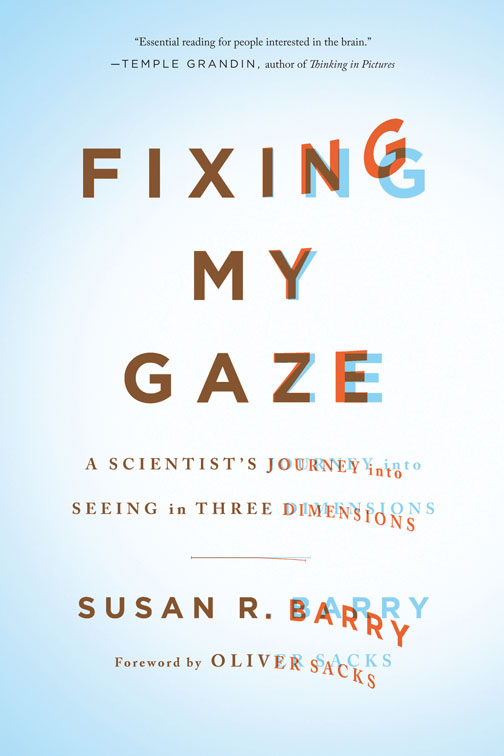

Now Barry, a neuroscientist at Mount Holyoke College, has written Fixing My Gaze: A Scientist’s Journey Into Seeing in Three Dimensions, to be published by Basic Books next month. Part memoir, part science journalism, the book describes her struggles in a two-dimensional world and the therapy that gave her three-dimensional vision, after nearly five decades without it.

Barry was cross-eyed from infancy; after three operations, her eyes appeared straight but remained subtly misaligned, which could not be detected in standard eye exams.

Ordinarily, the brain integrates the two-dimensional inputs from the two eyes into a single, three-dimensional image. But because Barry’s eyes were supplying such different visual information, her brain learned to alternate rapidly between them, making three-dimensional vision impossible.

Although Barry eventually earned a Ph.D. in biology from Princeton, she struggled with reading, sewing, and driving, tasks that become more difficult when the eyes don’t work in sync. Even after realizing she lacked three-dimensional vision, she did not understand that this deficit explained her struggles. Conventional wisdom holds that three-dimensional vision is relatively unimportant — without it, the brain uses other cues to judge spatial relationships.

“I felt that I was just a wimp, that I should be able to accelerate the car to 50 miles an hour and be comfortable with it,” Barry says. “Everyone else could.”

Her doctors offered no hope for change: Long-standing scientific understanding held that three-dimensional vision develops only during a short critical period in early childhood.

But when her eye problems worsened with age, she consulted a developmental optometrist, who prescribed vision therapy: eye exercises that use low-tech materials but draw on a sophisticated understanding of vision. Staring at a bead on a string, for example, trained Barry’s misaligned eyes to focus on the same point in space.

As therapy rewired her brain, Barry began to see in three dimensions, and she thrilled to the world’s new richness — the sharpness of edges, the roundedness of trees.

“This was an amazing experience,” Barry says, “and it went against everything that I had read and been taught and that I did teach. First of all, that my vision could change, and, second of all, that the change would be so overwhelmingly wonderful.”

In 2006, The New Yorker and National Public Radio ran stories about her experiences and about the emerging scientific consensus that the adult brain is far more malleable than once thought. The ensuing avalanche of e-mail from people with similar stories inspired Barry to write her own book, to spread the word about vision disorders, which often go undiagnosed while children struggle in school.

Deborah Yaffe is a writer in Princeton Junction, N.J.

No responses yet