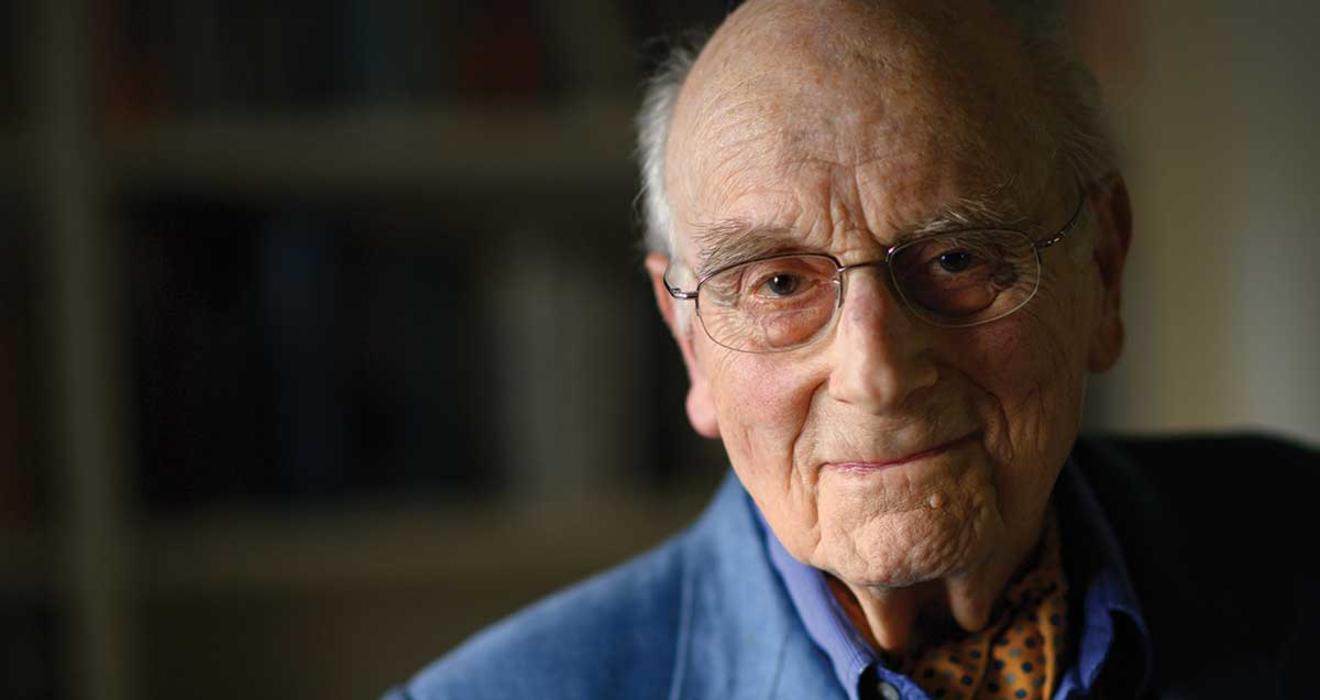

Editor’s note: PAW is saddened to hear that Victor Brombert died Nov. 26, 2024. University officials said the Princeton flag over East Pyne will fly at half-staff Dec. 4-6 in his memory. A memorial service will be held Thursday, Feb. 27 at 4:30 p.m. in McCosh 50.

Two years before he returned to France to fight the same Nazis his family had fled, Victor Brombert — then 18 years old and newly arrived, as a refugee, in the United States — saw Princeton University while on a day trip with his family to explore his new country. He had no way of knowing that he would one day become a professor there.

A family friend who was taking them to Pennsylvania made a special detour to Princeton, stopping at the corner of Witherspoon Street so that the refugee family could take in the American scene of abundance: busy shops; pleasant lawns; people walking around with books, looking, at every age, distinctly youthful.

The friend, a lawyer, waved toward the campus with a flourish that might have impressed a jury and said, “This is where Einstein teaches.”

Well, Einstein did give lectures at the University, though his faculty home was at the Institute for Advanced Study. The little tableau of American optimism stayed in Brombert’s mind for a long time afterwards, he says: “I had never seen anything like that in France. The façades of French schools are grim, military-looking.” But even then, as a teenager who had spent just a week in his new country, he was determined to return to the terrors he had left behind in Europe, this time with an army behind him. His journey back to the United States would be long and filled with harrowing turns.

Brombert belongs to a remarkable group of veterans called, today, the Ritchie Boys. During the Second World War, thousands of young refugees from Europe trained at Camp Ritchie, a military training facility in Maryland, to learn methods of combat, interrogation, and lie detection. Many of them, like Brombert, were Jewish. They fought with the American military in the lands they had recently escaped, helping to turn the course of the war.

Of late, the Ritchie Boys have been the subject of growing media attention — including, in May, on the television news program 60 Minutes. (Brombert appeared on the show, discussing the group’s training and casually explaining how to garrote a sentry.) In September, the book Ritchie Boy Secrets, by Beverley Driver Eddy, joined other recent histories of this unlikely fighting force. It’s not a history that Brombert is in the habit of telling. War puts us in stories outside our control; times of peace give us more freedom to write our own stories. For Brombert, that self-written story leads to the classroom.

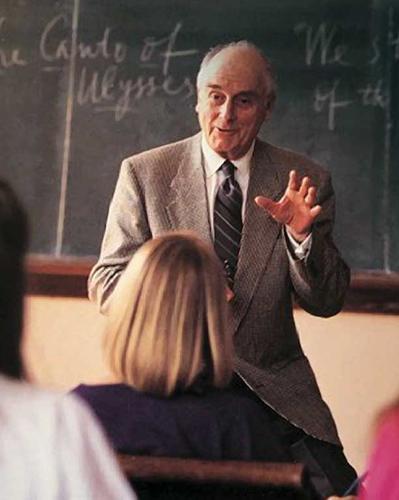

“My real passion is not war. It is teaching, which I have always loved,” Brombert told me when I spoke with him at his home in Princeton in the summer. “Whatever you write, I hope you will write something about my love of teaching.”

Brombert grew up in Paris. His parents were Russian Jews who fled to Berlin to escape the Russian Revolution and then, when Berlin became hostile to Jews, fled again to France. In 1940, his family escaped from occupied France and made its way through Spain. Passing from one country to another was exceedingly difficult, since it required exit visas, travel visas, entry visas, and other hard-to-get documentation, all of which had to be unexpired at the same time. At the last possible minute, his family assembled the necessary papers to go to America and boarded a ship that — when it arrived in New York — newspapers called “the floating concentration camp” because of the horrible living conditions and the on-board deaths from typhus and starvation. A banana freighter, the ship normally held 15 people along with its cargo; when Brombert’s family crossed the ocean, it held 1,200 refugees. “We were the bananas in the hold,” he says.

“Certain wars cannot be avoided, and … this one, against Hitler, had to be fought and won. But it had to be won precisely by those who hated war.”

He joined the Army as soon as the United States entered the war. “My parents were determined pacifists and made me read anti-militaristic books,” he later wrote in an essay for the Alumni Weekly. “Yet they knew that certain wars cannot be avoided, and that this one, against Hitler, had to be fought and won. But it had to be won precisely by those who hated war.”

When Brombert’s superiors realized he spoke German and French, they reassigned him to Camp Ritchie. In a memoir, Trains of Thought, he writes of this transfer: “Someone in the Pentagon, it would seem, had the bright idea that those foreign types in American uniform could be put to a different use. They spoke other languages, thus they were linguists. They had lived in other countries, therefore they must have insights into the mentalities of those we fought or liberated. And so, quite a few of us were sent to Camp Ritchie for training in military intelligence.”

Camp Ritchie was among the most important of the dozens of secret training facilities that the U.S. military ran on home ground during the war — often at country clubs or in national parks, which offered terrain that could support combat exercises as well as enough seclusion to keep the goings-on secret. At one camp, the administrators told the trainees that townspeople nearby had decided that the camp was an insane asylum. At Camp Ritchie, where trainers often used German uniforms and equipment to make exercises more realistic, local civilians — alarmed at the sight of German tanks and soldiers lumbering down the road — warned the government that the Germans were invading Maryland. After several false alerts, the locals got the picture.

“Camp Ritchie was my first university,” Brombert says. Many of his fellow trainees — who included lawyers, professors, and musicians — held advanced degrees, and during downtime, he listened to chatter about Piero della Francesca, Wilhelm Furtwängler, and Mozart.

“It was fascinating, fascinating,” he says.

In his classes, Brombert learned how to interrogate civilians, how to interrogate prisoners of war, and how to liaise with members of La Résistance. He memorized the whole hierarchy of the German and Italian armies, the insignia on their uniforms down through every branch, the look and capabilities of their cars and tanks and guns. He learned how to read aerial photographs, how to do reconnaissance in the field, and how to make sense of documents that had been captured from the front. He learned Morse code. He practiced finding his way around at night in unfamiliar terrain. He learned how to kill someone silently by using a stick to garrote them from behind.

In the fall of 1943, he was put on a ship to England. “Standing on the deck near the railing,” he writes in his memoir, “looking out at the other ships and the angry winter sea, I indulged in silly talk about fighting, liberating, heroic action, and the noble side of military servitude.” An older officer gave him a chilly look. “Tu as le virus,” he told Brombert: “You have the virus.”

Upon arriving in England, Brombert got his first taste of teaching. He joined up with the Second Armored Division, which was preparing to land in France as part of the landings in Normandy. Exactly where they would be landing was a closely guarded secret. Because Brombert had lived in France, the officers asked him to deliver a lecture about what they would find when they arrived. Even during this first tentative chalk talk, the teaching gods smiled on him.

“I had spent my summers in Normandy with my parents, in Deauville and Cabourg,” he says. “I wasn’t going to talk about that because that was too close to autobiography. So I invented a place and pointed to a map, which happens to have been exactly where we landed: Omaha Beach.”

“When we finally landed there, they were convinced that I had advance information — that I knew where we were going to land,” he adds. “But I didn’t.”

War is sweet to those who have not tried it. Somewhere in the muddy woods of Hürtgen, or while clinging to the bluffs of Omaha Beach as gunfire exploded above, Brombert lost the virus. He hauled himself through the grim work of pushing back enemy forces and interrogating civilians, but without his earlier enthusiasm. The purpose of interrogation was to gather simple, concrete tactical details: how many men were ahead, and where, and with what kinds of weapons. Witnesses could be misleading, accidentally or on purpose — as when a French woman said danger lay to the right and pointed to the left.

The experience gave him, he says, an enduring education in interpretation: “You had to learn how to hear things between the words, which is like reading between the lines. That was very important training. One had to be very keenly sensitive to not only what people said, but how they said it.”

The Ritchie Boys “took part in every major battle and campaign of the war in Europe,” according to Bruce Henderson, the author of a book on their exploits. The U.S. Army credited them with capturing some 60 percent of the credible combat intelligence that it acquired. Typically, a team of Ritchie Boys embedded with an Army unit, performing interrogations and reconnaissance as the soldiers pushed forward into new territory. Often the teams were small, but they performed essential duties that no one else could. Brombert worked with two different teams, one in France and one in Germany. His teammates came from all kinds of national backgrounds, from German to Czech to Latin American to British.

Once, a Hungarian Ritchie Boy with the surname Lukács got Brombert’s team into serious trouble. When they arrived at an American guard post, Lukács caused alarm by giving the password in a strong Hungarian accent. “We could have been shot right there,” Brombert says. The guards were suspicious that the men were not actually U.S. soldiers: “They were trigger-happy because the Germans had infiltrated, in American uniforms, our troops in the Battle of the Bulge.”

The guards asked a question designed to check the interlopers’ American credentials: “What’s the Windy City?” Nobody knew. The guards gave them another chance: “Who won the World Series?” Nobody knew. They were all recent American immigrants.

“I talked very fast and convinced them to take us to headquarters,” Brombert says. “I explained the whole situation, what kind of outfit we were.”

In another unit, Brombert says, a Ritchie Boy got killed returning from the latrine at night because he gave the password in a German accent.

Slowly, while making his way through the shattered cities of Europe, Brombert realized that he wanted a life of learning. Once the war was over, he got perhaps his first experience of scholarly research while working with a de-Nazification task force in Germany, when he hungrily read and annotated everything he could find about the Nazis’ rise to power. But what he had learned during the war about politics and human character exhausted him: the way French civilians condemned their neighbors as collaborators while excusing themselves; the way German civilians refused to condemn anybody or speak of what had happened; the way Americans left Nazi officials in place in the name of keeping the engines of the German state running. In an episode that he later described with more shame than is perhaps warranted, Brombert lost control while questioning a Nazi official, yanking him around by his beard and shouting at him, “Did you know about the camps?”

He was ready for something new. He enrolled as an undergraduate at Yale University. Twenty years later, he left Yale’s faculty to teach at Princeton.

Princeton is not the historical teaching home of Albert Einstein, but it is the historical teaching home of Victor Brombert. He became a beloved professor of Romance and comparative literature, whose influence at the University continues to this day.

“I loved every moment of my teaching profession,” he says. “I liked the small seminars, I liked the discussion classes, I liked the large lectures. But what I liked most of all, I think what gave me the greatest satisfactions, also of a histrionic nature, is the large lecture course I had for a freshman class in European literature. I had between 300 and 400 students every year.”

One day in 1994, while Brombert was giving a lecture on Virginia Woolf in his freshman lecture class, a student in a balcony seat started shouting, “Brombingo!” The campus humor magazine, Tiger, had published a bingo card that listed Brombert’s pet topics and favorite phrases: Nietzsche, Dionysus, epiphany, black sackcloth, Pascal’s human condition, and more. (Some of these topics came from Brombert’s interest in the work of Thomas Mann, a refugee writer who taught at Princeton after fleeing Nazi Europe in 1939.)

When he learned about this teasing from his students, Brombert felt deeply moved. “For teasing is usually a sure sign of fondness,” he later wrote in an essay on teaching. “And playfulness, the ludic element, I told myself, should be at the heart of learning and of teaching. Playing with ideas is never a frivolous activity. This is when we are at our best.”

Between classes, Brombert sometimes lifted his voice in song as he walked across campus, spending a few moments in the life he might have led as an opera singer had history not pushed him in a different direction. John V. Fleming *63, an emeritus professor of English and comparative literature, recalls Brombert’s “high-decibel rendition of famous Italian arias as he traversed the quad from its southeast corner by Washington Road along the path leading to his office in East Pyne. His ‘Che manina gelida’ was second only to Pavarotti’s and once garnered spontaneous applause from a large classroom of students awaiting a Chaucer lecture in McCosh Hall.”

“It was famous that Victor had somehow the most elegant office in East Pyne, and that it was a kind of salon,” says Leonard Barkan, a professor of comparative literature. “Victor has the most spectacularly complex and enjoyable sense of humor. Just the way he looks at you when you’re talking, you know he’s traveling through a multiplicity of languages and cultures and looking at what you’ve claimed through multiple points of view.”

The Brombertian element that remains in the Department of Comparative Literature today surely includes the department’s sense of irony. This is a department that takes irony seriously, so to speak — that has spent serious time teaching and writing and thinking about irony as a way to embrace cultural multiplicity and resist the dangers of ideological absolutes. Brombert’s style as a teacher and colleague, says another of his colleagues, Maria DiBattista, accentuates “irony, but not irony that puts people down or cuts. It’s very generous. It’s very kind.”

Brombert lights up with recognition when I mention this to him.

“This is one reason I like, not the irony of a Voltaire, which is very cutting, but the irony of a Stendhal,” he says. “It’s marvelous. It’s marvelous. And it is an irony that goes together with tenderness. Mozart is that way. The operas of Mozart, The Marriage of Figaro. I am very moved by what Maria has said.”

Of course, he gave more than a tone to the University: decades of course content, scores of supervised theses, some 15 books written and edited. In 2018, almost 20 years after he retired, Brombert wrote an essay for The New Yorker that described academia with a young person’s awe: “When I reflect on my nostalgia for the decades of teaching, Wordsworth’s striking image of ‘pensive citadels’ often comes to mind. Harkness Tower in New Haven and the bell tower of Nassau Hall in Princeton were for me emblems of serene contentment in academic strongholds, especially after the chaos of the war.” He saw beauty and then — after leaving to liberate France — returned years later and added to that beauty. Or at least this is one way of glossing what Brombert calls his “fate of Princeton”: the idea that he was always, if he survived the war, going to find his way back here.

“There and back — 25 years later, more than that,” he says. “Because that is a thing I still remember, my astonishment. It was a wonder, this view of a campus.”

Stony Brook University professor Elyse Graham ’07 is the author of You Talkin’ to Me?: The Unruly History of New York English.

6 Responses

Peter J. Kurz ’64

4 Years AgoGoheen’s Fort Ritchie Experience

Thank you for your excellent cover article and interview with Professor Victor Brombert (“A Ritchie Boy,” November issue).

During the past many decades I have very much enjoyed at least three — usually more — articles in each issue of PAW. For many years I lived within a few miles of Fort Ritchie and, therefore, it’s not surprising that many of these issues of PAW were actually read near Fort Ritchie, sometimes north, sometimes south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Your most recent issue brought back fond memories of this historic and important Army base, even if now abandoned, yet working on its metamorphosis.

For the 50th Reunion Book of my Class of 1964 I was asked to write about President Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48. I was amazed when I learned that he was one of the many distinguished Americans who rotated through Fort Ritchie during World War II. Here’s an excerpt from what I wrote at the time (pages 16 to 24 of Fifty Years Behind the Eight Ball):

... After one year of graduate study in Princeton’s Department of Classics, in 1941, he joined the Army. As 'a 1st Lt., Inf.,' in 1943 he entered Camp (later Fort) Ritchie in the hills of Western Maryland, where a succession of remarkable, select classes of linguists and others with specialized skills were undergoing training before overseas assignments (such as the Ritchie Boys of film-fame). Lt. Goheen's Army records note that he was 'last employed by Princeton Univ. N.J. as Freshman Soccer Coach.' On the upper right hand corner (in caps) there is a notation that he knew French and Marattri; at the bottom, that he was 'not available for assg without approval of G-2, War Dept.' ...

I hope that many of your readers — our classmates, colleagues, and friends — will find these tidbits both informative and of interest.

William G. Carpenter *85

4 Years AgoA Delightful Lecturer

I would also like to thank the editors for the excellent article on Professor Victor Brombert, whose graduate course on Dickens and Flaubert I took in the early 1980s. He is a delightful lecturer. My dissertation on wedding and tomb imagery in Joyce and Mallarme owed much to his critical theme of obsessive metaphor.

Jane Elizabeth (Spivak) Hughes ’77

4 Years AgoA Teacher of Lasting Lessons

Professor Victor Brombert (“A Ritchie Boy,” November issue) was my thesis adviser, and it was a privilege and an honor to work with him. As the world’s leading expert on Gustave Flaubert, he was perfect for guiding me through my work on Madame Bovary; but it is his gentle warmth, wisdom, and humor that I remember best. I am particularly struck by your comment about his lifelong ability to read beyond the words and the language to what lies beneath. Studying literature with Professor Brombert helped me develop those skills in my own work as a professor and author.

I only wish I had known of his background then, but I was cautious about revealing my Jewishness on campus in those days; through your article, I am still learning life lessons from Victor Brombert.

Lawrence H. Phillips ’70

4 Years AgoAnother Notable Princeton Ritchie Boy

I very much enjoyed the article about Professor Victor Brombert and his experiences as a Ritchie Boy. In fact, I was inspired to read the book by Beverley Driver Eddy in which he features prominently. I was pleased to learn from the book that future Princeton president Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48 h’70 was also a Ritchie Boy. He served as an intelligence officer in the Pacific and completed his service as a lieutenant colonel. His service and courage were exemplary as well, and I hope PAW will do a follow-up article about him.

Stephanie Oster

4 Years AgoJoin Professor Brombert for a Virtual Talk Hosted by the Friends of Princeton University Library

The Friends of Princeton University Library will be hosting Professor Brombert on Sunday, Nov. 14 at 3 p.m. for a virtual talk about his remarkable life, including his time as a Ritchie Boy. Entitled “From Berlin to Omaha Beach and Back: A Survivor’s Metaphors,” the event will be hosted on Zoom and is open to the public. Registration is required: https://princeton.zoom.us/j/92590809981

Longtime Friend of PUL, Princeton University alum, and former editor of PAW Landon Jones will moderate the session.

We encourage PAW readers to join the event.

Zanthe Taylor ’93

4 Years Ago‘The Traveling Explorer, the Exploring Traveler ... ’

In four years of wonderful undergraduate education, Victor Brombert was one of the most memorable and excellent professors I had — his lectures in our Lit 141 class for freshmen were erudite, eloquent, witty, and complex beyond compare and taught me what enormous pleasure critical analysis could give. I always regretted taking only that one class with him — I probably imagined every professor would be like him! — but how lovely to read that class was special for him as well. And perhaps he will smile to know that my friends and I, 29 years after graduation and more than 30 after taking his class, still quote him and try to (lovingly) mimic his incomparable way of connecting words and ideas.

It’s fantastic that he’s being celebrated, and I hope he continues to enjoy the well-deserved praise and gratitude from all his former students — even those who were callow freshmen in his Lit 141 lecture. To me he will always be the beau ideal of a humanities professor.