Sarah Churchwell *98 on ‘America First’

The book: On the 2016 campaign trail, Donald Trump claimed that the “American Dream was dead.” In response, he offered an ideology of “America First,” meant to push the nation back toward its former greatness.

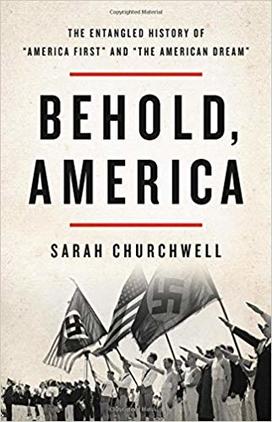

The notions of the “American Dream” and “America First” carry strong connotations of national identity and opportunity, which Sarah Churchwell *98 explores in Behold, America: The Entangled History of “America First” and “The American Dream.” (Basic Books). Through a study of the terms’ use and political context from the early 1900s to the present, Churchwell shows how the current use of both phrases is dangerous to democracy — as signals of prejudiced nationalism or simplistic views of opportunity.

Opening lines: There is great power in loaded phrases, as anyone willing to pull

the trigger knows. ‘Sadly, the American dream is dead,’ Donald Trump proclaimed on 16 June 2015, announcing his candidacy for president of the United States. It seemed an astonishing thing for a candidate to say; people campaigning for president usually glorify the nation they hope to lead, flattering voters into choosing them. But this reversal was just a taste of what was to come, as Trump revealed an unnerving skill at twisting what would be negative for anyone else into a positive for himself.

By the time he won the election, Trump had flipped much of what many people thought they knew about America on its head. In his acceptance speech Trump again pronounced the American dream dead, but promised to revive it. We were told that the American dream of prosperity was under threat, so much so that a platform of ‘economic nationalism’ carried the presidency.

Reading last rites over the American dream was shocking enough. But throughout the campaign Trump also promised to put ‘America first’, a pledge renewed in his inaugural speech in January 2017. It was a disquieting phrase for a presidential candidate, and then president-elect, to keep using. Think pieces on the history of ‘America first’ began to sprout up in the national press and on social media, informing their audiences that the slogan ‘America first’ stretches back to the Second World War, and to the efforts of the America First Committee to keep the United States out of the European conflict. ‘America first’ had been invented by high-profile isolationists like Charles Lindbergh, they explained, whose sympathy with the Nazi project was often inextricable from an avowed anti-Semitism. ‘America first’, they said, was a code for neo-Nazism.

Meanwhile, other pundits were weighing in on the American dream, as writers asked if it was indeed dead. Nearly all of these pieces began with a shared understanding of what the American dream was supposed to entail: namely, upward social mobility, a national promise of endless individual progress. But now, thanks to epidemic levels of inequality, that dream was widely viewed as under threat, a story that had been endlessly recycled across the international press for the decade since the financial crisis beginning in 2007. Trump had weaponised this inequality, they said, convincing his followers that only an outsider could redeem a corrupt system. (That he was in fact a plutocratic insider, a self-styled billionaire corporate tycoon, was hardly the last bit of cognitive dissonance his followers were prepared to disavow.)

But most did not question what the American dream meant; they only debated its relative health. A Guardian editorial from June 2017, for example, called ‘Is the American Dream Really Dead?’, summed up not only the questions everyone was asking, but the premises from which they began.

The United States has a long-held reputation for exceptional tolerance of income inequality, explained by its high levels of social mobility. This combination underpins the American dream — initially conceived of by Thomas Jefferson as each citizen’s right to the pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. This dream is not about guaranteed outcomes, of course, but the pursuit of opportunities . . . Yet the opportunity to live the American dream is much less widely shared today than it was several decades ago.

Few would dispute any of this: the American dream is widely understood as a dream of personal opportunity, in which ‘opportunity’ is gauged primarily in economic terms, and those opportunities are shrinking. The idea that the American dream was ‘initially conceived’ by Jefferson is similarly axiomatic, despite the fact that happiness and opportunity are not, in fact, synonymous.

But what Jefferson conceived – at least in terms of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness – was a dream of democratic equality. He doesn’t mention economics, or opportunity, for good reason. In fact, Jefferson took John Locke’s phrase, ‘life, liberty and property’, and changed property into happiness. While it is true that in the eighteenth century ‘happiness’ was often used to mean ‘flourishing’, which can clearly imply prosperity, Jefferson nonetheless removed specific economic guarantees from the nation’s founding entitlements. Democratic equality and economic opportunity are not the same thing, but the American dream has, for decades, been used as if they are.

Reviews: “[A] richly engaging account of the expressions ‘the American Dream’ and ‘America First’ . . . Behold, America is enormously entertaining. Churchwell is a careful and sensitive reader, writes with great vigour and has a magpie’s eye for a revealing story.” —Sunday Times (UK)

No responses yet