The University’s endowment enjoyed a 12.7 percent return for the year ending June 30, rising to an all-time high of $22.7 billion, officials announced in October. After taking into account gifts and spending, the endowment increased in value by $1.7 billion.

The performance was not as strong as in the preceding year, when the endowment had a 19.6 percent return. The decade-long average annual return of the endowment declined from 10.5 percent in 2014 to 10.1 percent in 2015.

Still, University officials say they are happy with the results, which outpaced the benchmark Standard & Poor’s 500 index. The S&P 500 increased only 5.2 percent in the year ending June 30 — a period that saw substantial volatility in the global economy.

“The ball bounced our way a lot,” said Andrew Golden, who manages the endowment as the president of the Princeton University Investment Co. (Princo). “There was a lot of good luck involved.”

Golden said the returns were driven by long-ago investments that finally paid off and unexpectedly swift profits from recent trades. In particular, the University had put money into biotechnology and health companies, as well as venture capital-backed firms. Profits from those investments were realized this year.

“What’s satisfying is that a very good portion of the portfolio involved ... realizations of past efforts, and a lot of work done by us and our external managers came to fruition this year,” Golden said. He noted that investors are starting to fully appreciate advances in the biotechnology field that will allow more personalized medicine, as well as the potential of the so-called technology “unicorns” — private startups that have received valuations of more than $1 billion.

While some market commentators have warned that there might be a bubble in the startup market, he said Princeton is somewhat insulated from those concerns because it has begun to realize some of its big investments. But he also added that these unicorns enjoy substantial revenue and a degree of profit, unlike those of the infamous dot-com boom of the late 1990s.

Another source of strength last year were currency hedges. As global markets swooned, the U.S. dollar rose strongly against the euro and the yen. The University bought protection against those fluctuations, which paid off when markets stabilized.

The move was atypical, Golden acknowledged, because Princo long has argued against trying to time the market. Occasionally, he said, Princo will try to bet on market fluctuations — “when there is a very large opportunity. We say we’ll shoot a very slow-moving duck.”

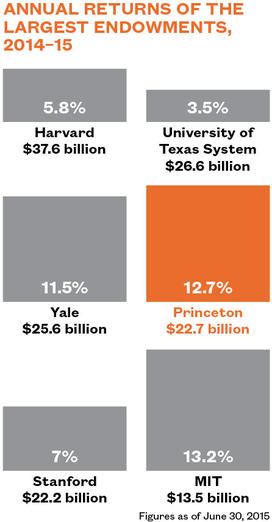

This year’s 12.7 percent return placed Princeton at the top of the Ivy League, with Harvard posting a 5.8 percent return and Yale marking an 11.5 percent increase. MIT was a leader among highly selective schools with a gain of 13.2 percent. For the past decade, Princeton and Columbia are tied for the highest average annual endowment return.

Since the end of the fiscal year, some of the gains have been lost as markets have been battered by developments in Europe and Asia. Golden said in early October that the endowment was down a few percentage points since June 30.

“The new fiscal year is off to a choppier start, and we’ve not been immune to that,” he said.

The University has substantial exposure to global markets. It seeks to invest, on average over the long term, 9 percent of its money in domestic stocks, 6 percent in developed countries’ stock markets, and 10 percent in emerging markets. It aims to place 25 percent in private equity; 21 percent in real estate, natural resources, and other “real assets”; and 24 percent in a category called independent return, generally funds with specialized strategies. It also puts 5 percent in fixed-income investments. The actual allocations can vary somewhat due to adjustments and market fluctuations.

In the past year, domestic stock markets were the biggest winner in the portfolio, up 33 percent. That was followed by private equity at 22 percent, international emerging markets at 15 percent, developed-country stock markets at 12 percent, independent return at 5.5 percent, and fixed income at 1 percent. Real assets were down less than 1 percent.

The results were reported during a period of renewed scrutiny over how major universities are spending their money. Congress has been questioning whether wealthy universities are spending enough of their investment returns, while at the same time asking if too much is being spent on executive compensation and administrative costs.

Other questions about the nature of university endowments — and their tax-free status — have been raised because of mega-donations, such as a $400 million gift by hedge-fund manager John Paulson to Harvard, and in writings by inequality economist Thomas Piketty suggesting that schools were benefiting from growth in their investments without expanding social mobility.

An op-ed piece in The New York Times by a University of San Diego law professor accused wealthy schools of “hoarding money,” calculating that at the schools with the five largest endowments, private-equity fund managers are receiving more than students.

Golden said Princeton’s goal “is to spend as much as possible consistent with two constraints, and those constraints are underappreciated.” First, he said, the endowment is meant to last for centuries, and so the University has to be measured in how it spends. Second, the endowment pays for about half of the University’s budget. “It’s critical that the spending streams be stable,” he said. “So in good years we’re going to be spending less as a percentage of the endowment than in lean years.” Princeton aims to spend 4 to 6.25 percent of its endowment each year, a goal it has been hitting in recent years.

Golden also took issue with those who might criticize the fees paid to outside managers for investing the University’s money. “We have shown that whatever fees we are paying seem to be worth it, due to our returns,” he said. “We always look for good value in fee structure and for aligned interest, and that does not necessarily mean minimizing fees.”

No responses yet