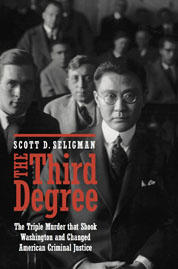

Scott D. Seligman ’73 Brings to Life an Epic Supreme Court Case

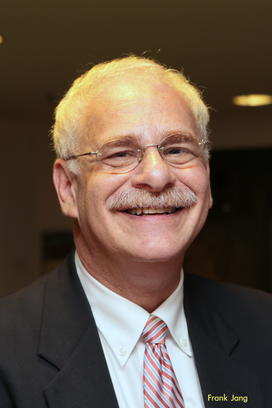

The author: Scott D. Seligman ’73 has written several books, including Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York’s Chinatown and The First Chinese American: The Remarkable Life of Wong Chin Foo. He has written for the Washington Post, the Seattle Times, and the China Business Review, among other publications.

Ringing in the Year of the Goat was a welcome break from the work of the mission, which had been established in 1911 to look after the hundreds of Chinese scholarship students studying at universities across the United States. It had been directed from the start by Theodore Ting Wong, 43, a Shanghai-born alumnus of the University of Virginia. A well-respected scholar adroit in both cultures, Wong was assisted by Chang Hsi Hsie, 32, the organization’s treasurer, an affable man, who had served as registrar at China’s Tsinghua (Qinghua) University before coming to the U.S. The third man, the mission’s secretary, was 21-year-old Ben Sen Wu. Bright and sociable, he was a graduate of prestigious Peking (Beijing) University.

All three men were diplomats, although they were not domiciled at the Chinese Legation on 19th Street NW. Instead, they lived and worked a few minutes’ walk away in a row house on Kalorama Road, just a few doors in from stately Connecticut Avenue. Hsie and Wu, scholarship recipients themselves, were also part-time students at George Washington University.

Dr. Wong and Mr. Hsie were dining at the upscale Nankin Restaurant on Ninth Street NW, guests of T.C. Quo (Guo Taiqi), a high-ranking Chinese diplomat passing through on his way to France. The fate of territories in China that had been controlled by Germany before World War I was to be discussed at the Paris Peace Conference, and Quo was serving as a technical adviser to the Chinese negotiators.

The host had arranged a sumptuous private dinner for 13, replete with silver service and table linen, in a private room on the second floor of the restaurant, which advertised that it catered “only to the refined.” It was a congenial affair, and “the best of spirits prevailed throughout the evening,” Quo said later. The meal began at 7 p.m. and ended about three hours later.

Hsie left first, with a friend from the legation. The pair took a streetcar and got off three blocks from the mission at about 10:30 p.m. Declining an offer to return to the legation for a chat, he proceeded home.

At a few minutes after 10, Dr. Wong departed in the company of the host, his family members, and a secretary from the legation. He played with the Quos’ little girl on the streetcar before the entire group got off at Connecticut Avenue and S Street NW. The walked a block to the Cardova Apartments, where the Quos were staying, and there they parted company at about 10:30 p.m. Then Dr. Wong made his way back to the mission, about 10 minutes away on foot.

Wu, low on the mission’s totem pole, had gone to a separate dinner. After class that Wednesday evening, he had headed to for the Oriental Restaurant, a Pennsylvania Avenue chop suey joint just across from the municipal building. He had accepted an impromptu invitation from a fellow student, and they were joined by two friends. At dinner, Wu apologized to his classmate for having recently been so unavailable; he had been caring for a sick guest, he explained, who had taken up much of his time and energy but hand finally returned to New York. After dinner, the quartet departed the restaurant just before 8 p.m., when Wu boarded a streetcar and returned to the mission.

Dr. Wong, Hsie, and Wu were never seen alive again.”

Reviews: “The Third Degree provides the human story behind a seminal Supreme Court decision. Scott D. Seligman, a meticulous researcher and an excellent writer, fills gaps in our knowledge with a story that has never been told before.” —Ira Belkin, executive director of the U.S. Asia Institute

No responses yet