Searching for Jewish Cuba

Anthropologist Rush Behar *83 travels back to her native land

For anthropologist Rush Behar *83, Cuba is at once a homeland and a filed site. Born in Havana, she moved to New York City as a young child with her parents, who were among thousands of Cuban Jews who left the island, mainly for the United States, to escape the economic turmoil of the 1960s. Although intermarriage and cultural assimilation make exact numbers difficult to assess, between 15,000 and 17,000 Jews had settled in Cuba by 1959, and today, between 1,000 and 1,500 remain.

Though Cuba had long captivated her imagination, Behar had no memories of life there and didn’t return until 1979, when she traveled to the island with a group of Princeton professors and students. Since the 1990s, she has gone back again and again, becoming a recognizable face in the synagogues and small communities of Jewish Cuba.

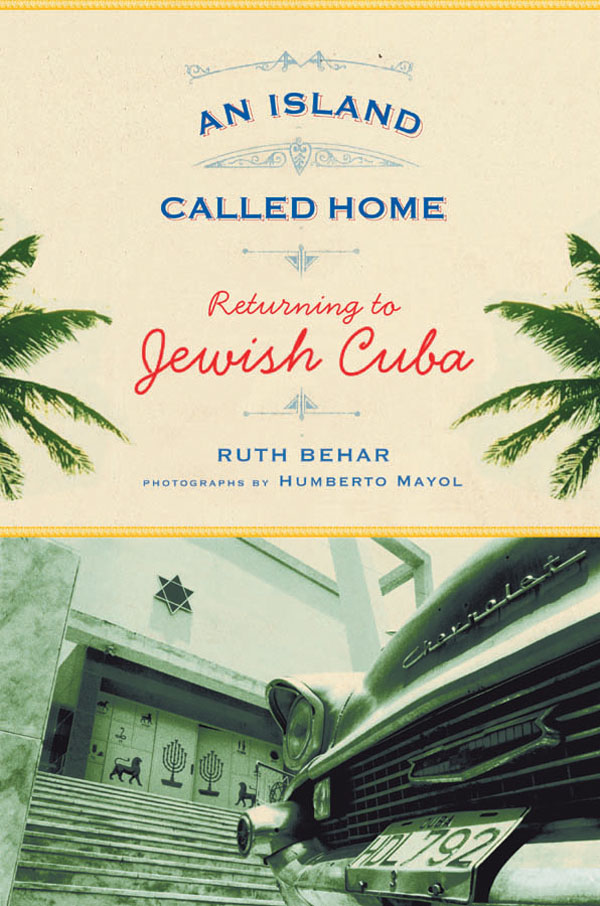

She made a documentary film, Adio Kerida, about the Sephardic Jews of Cuba in 2002, but she wanted to tell stories of Jewish Cuba as a writer. The result: An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba, which was published by Rutgers University Press in November. An account of her journey back to Cuba, her book is part memoir, part travelogue, and part visual ethnography.

In collaboration with Cuban photographer Humberto Mayol, Behar collected interviews with and images of hundreds of Jews living in Cuba, from a scientist who hopes to erect a statue to his hero, Albert Einstein, to an activist from the town where Che Guevara is buried who advocates for a Holocaust memorial. There are members of the “lost generation” — those who came of age in the 1960s and rejected Judaism in favor of revolution — whose children now strive to reconnect with their Jewish heritage. A constant thread in Behar’s prose is an oscillation between alienation and belonging, echoed in some of her own thoughts on her search for Jewish identity in Cuba. When she embarked on the project, Behar sought to recover her memories from their “phantomlike existence” in family photographs, and instead found a voice as a storyteller for others.

Many of these photographs of the people in her book are, as Behar puts it, “haunted by absence,” because the people in them no longer live in Cuba. They are part of a continuing trend of immigration to Israel, where hundreds of Cuban Jews have traveled to find a new start or gain access to life in the United States. Still, “I feel there will always be a Jewish community in Cuba. It will be small, but it won’t disappear,” says Behar, a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan and a poet, essayist, and winner of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant in 1988.

Doing fieldwork in her country of origin was a complicated enterprise, says Behar, since anthropologists are meant to document a community without altering its rhythms. In Cuba, maintaining such distance was impossible. Through writing An Island Called Home, Behar says that she has both “gained and lost” a home in Cuba — though her family’s Cuba no longer exists, she nonetheless has nurtured her own connections to the island as a scholar, a tourist, an artist, and a friend. Of the voices in her book, she says, “Their stories became mine, [and] they all haunt me in their own way.”

Jane Carr ’00 is a writer and graduate student in New York City.

No responses yet