In Short

Geosciences postdoc Karin van der Wiel and lecturer Gabriel Vecchi have found an everyday casualty of CLIMATE CHANGE: mild weather. Their paper, published in the journal Climate Change in January, predicts that within a century the global average number of days on which the temperature is between 64 and 86 degrees Fahrenheit will drop by 10. Tropical regions may be hit even harder, losing between 15 and 50 mild days. Shifting focus from extreme events to the decline in mild weather could help the public better conceptualize climate change, they write.

We feel better about our choices when other people agree with them — but especially when those people display CONFIDENCE. That is the finding by neuroscientist Nathaniel Daw and colleagues published in the Journal of Neuroscience in December. Studying 23 subjects, they found that trust in confident peoples’ beliefs lit up a different part of the brain’s reward system, which evolved later than the part sparked by trust in their own or popular beliefs. They conclude that humans evolved the ability to discern confidence to help them make more discriminating choices. By Michael Blanding

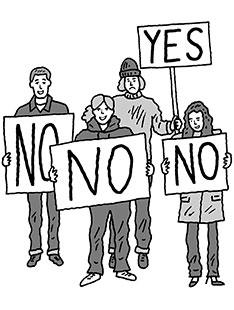

No responses yet