A Special Anniversary: When Princeton Opened Its Doors

In September 1969, 101 female freshmen and 70 female transfer students enrolled as Princeton undergraduates. They were not the first women students on campus: The first female graduate student enrolled in 1961, and undergrads from other schools, including women, began studying languages deemed critical to American security at Princeton two years later. With the enrollment of women as full members of the undergraduate student body, the era of Princeton as an all-male school was history.

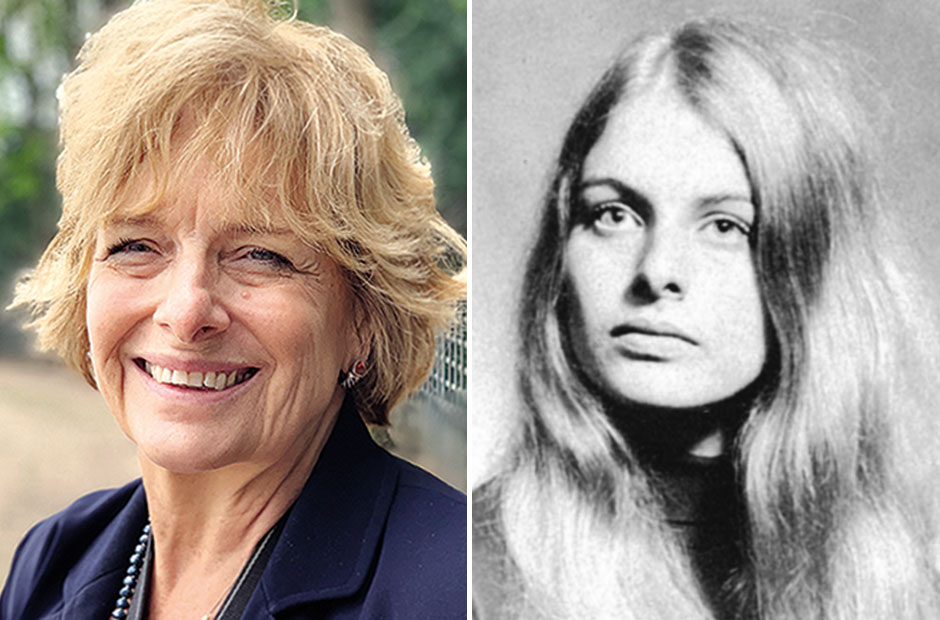

PAW asked four members of the Class of 1973 to recall their early weeks on campus and the way their experiences resonated throughout their lives.

Tigers and Pussycats

By Lisa Dorota Tebbe ’73

Tigers and Pussycats,” “Kittens Ready to Invade Halls at Princeton,” “Minichicks Arrive at Princeton” — inane headlines with photos of me in newspapers worldwide. These bizarre reactions to my first day at Princeton confounded this naïve, excited, and enthusiastic 17-year-old from rural New Jersey. Never before had I been called a pussycat, kitten, or minichick (whatever that was).

As I stepped on campus, the reporters and photographers descended on all of the students, but the women attracted the most interest. At first, I found the frenzy fun and exciting. Eagerly I posed for pictures outside Pyne Hall, where I was delighted to share my basement-level double with June Fletcher, my childhood friend. The pictures were staged: In a photo of June and me carrying books and suitcases, which ran in the New York Daily News, the luggage was empty.

I discovered how important women are — and will always be — in my life, and I learned how to thrive in a man’s world.

Greater absurdity soon ensued. Boys dropped through our ground-level basement window and raced through our room to get into the dorm. Within a few days, June was targeted because she had won the “Miss Bikini” beauty contest during the summer, and had painted her bicycle with tiger stripes. As a result of this publicity June and I were unusually visible and often shunned and avoided — even more than the other women seemed to be. The few dates I went on were strange, awkward, and painful. Male friends were few and far between. Was this really what life at Princeton University would be like?

Optimistically I started my classes and hoped that getting to know other students in academic environments would be more comfortable, more familiar. Surprises lay in store, however. In my 300-level German class of about 20 students, I was the only woman, and no one would sit next to me. Day after day, the same situation made me more and more anxious, so I began coming late to class to ensure that I could sit next to someone. I realized that my neighbor (whoever he might be) wouldn’t speak to me, but at least I wouldn’t feel like a contagious freak in the middle of the classroom. To my disbelief, my math instructor called me at my dorm to ask me to join him on an out-of-town weekend. Did he really think that was why I was at the University?

Chemistry was invigorating and included afternoon labs in the Frick basement. Imagine my shock when I learned that there were no women’s bathrooms in the building. Women had to leave Frick, cross Washington Road, and enter Firestone Library to find a restroom. Several of my exams were returned with correct answers marked wrong, forcing me to approach the male grad student to request clarification. He would say, “Oh, you’re right. I’m so sorry,” as he changed my grade with a smirk on his face. A midterm exam was marked with an A and “Nice perfume!” Slowly I was stripped of my delusions that I was attending a coed school. Clearly Princeton was a man’s school with a handful of women attending.

As the early excitement and novelty wore off, life settled into a difficult and solitary routine. I retreated into books and academics with my favorite places being Firestone Library, Prospect Garden, the Chapel, and Pyne Hall, of course. Isolation and loneliness continued until the middle of sophomore year. Yes, it was a long time — but a time of tremendous growth and personal discovery.

Why did I stay at Princeton? you ask. Giving up and embracing failure was never an option. A core set of dear friends supported and encouraged me. I discovered how important women are — and will always be — in my life, and I learned how to thrive in a man’s world. I built the strength to be independent, to not judge myself by headlines and rumors, to know myself and protect myself.

Eventually, I found my place at Princeton, and I loved it. I loved it. My classmates, dear friends, professors, the campus, the opportunities, the learning, the precepts, the football games, Tower Club, Reunions, the magnolias, the challenges — I loved them all. I will be forever grateful to have had the opportunity to be part of this remarkable institution. I have even learned to treasure the difficult lessons, as tough as they were, of that first year. Now privileged to serve as our class secretary, I go back to Old Nassau all the time. Tears spill down my face at every P-rade as the Class of 1973 marches through our stunning campus carrying the banner “Coeducation Begins.”

Those early, difficult times at Princeton prepared me for the world I would enter upon graduation. I have lost count of how many times since Princeton I was the “first woman” this and the “first woman” that. No problem. As the saying goes: “Been there, done that.” In fact, I was proud and ready to be first. Being ignored by my classmates helped me find my voice, a voice that has served to speak up in the countless times I have been unfairly dismissed, disregarded, or disrespected since my freshman year. The times of solitude in the Chapel, at the library, in the gardens, reconnected me with a faith that has sustained and nourished me my entire life. After the initial agonizing trials at Princeton, I knew I could face just about anything and have the confidence that I would survive. Better than survive — this Tiger would succeed.

Once Upon a Time in New Jersey

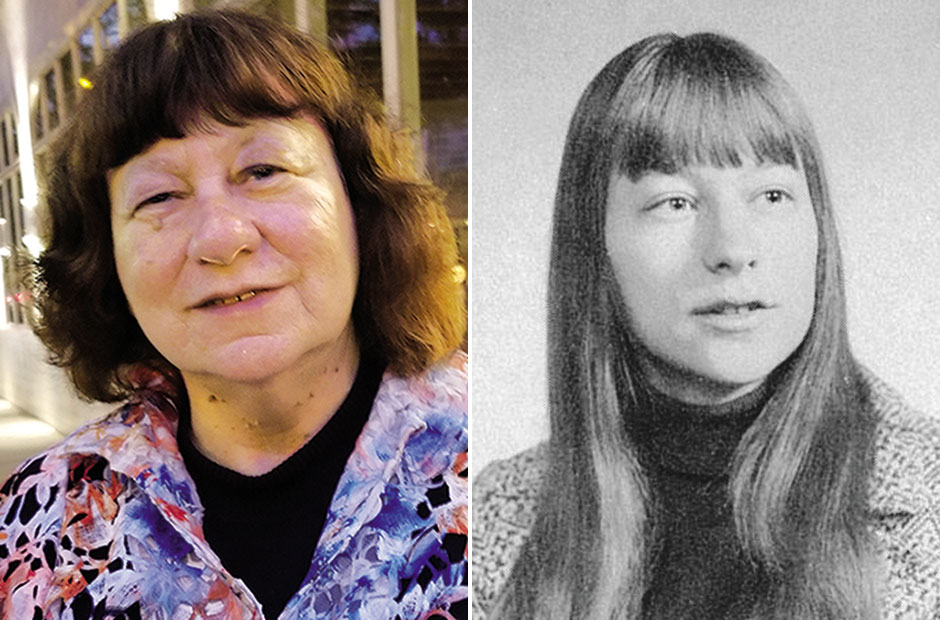

By Carol Obertubbesing ’73

Princeton has been the defining experience of my life, but it was never a clear path. Growing up in Union City, N.J., I was considered a “disadvantaged” student. However, in the summer of ’69, I was riding high: I had close friends, I was yearbook editor and class valedictorian, America had just put a man on the moon, people were coming together at an event called Woodstock, and I was going to be a pioneer in Princeton’s coeducation “experiment.”

On move-in day, activity was everywhere. Over the summer Pyne Hall had been renovated for the arriving “coeds.” Locks were installed on the doors; bathrooms had doors on toilet and shower stalls (men’s dorms did not); new furniture had been purchased; and kitchens and laundry facilities were installed (women cook and clean, right?). The locks were gone in a week or so, and by the time I graduated there were coed dorms. Many male students resented small dorm rooms turned into quads and all the fuss over women.

I remember crowds of people, cameras flashing, my first significant relationship, and a world completely different from any I had experienced. As the excitement wore off, insecurity took over. When I spoke in class, everyone turned around as if I were an exotic animal — partly because I was often the only woman there and partly because I had a “Jersey accent.” I stopped talking in class. I also did everything I could to get rid of my accent and to feel part of this new world. When I returned home, I was accused of “tawking funny” and “putting on airs.” Now I seemed to belong to neither world.

When I spoke in class, everyone turned around as if I were an exotic animal — partly because I was often the only woman there and partly because I had a “Jersey accent.”

“Commons” dining hall was noisy and stark. The lack of residential colleges meant there was little social life for freshmen and sophomores. I tried to join the staff of The Daily Princetonian but was discouraged by my interviewer. Few sports were available to women; I tried tennis but couldn’t compete with those who had played for years. I’d come to Princeton in part because of the open-stacks library and started to spend more time at Firestone, but most of my classes required a book each week, so I struggled and lost my love of reading. (Later I read Love Story for pleasure; while it may not have been great literature, it did rekindle my love of reading.) Had I become engaged in an extracurricular activity, I might have found more camaraderie, but instead I felt as if I didn’t belong. This crystallized later that year when a proctor would not let me return to Pyne Hall because he didn’t believe I — a woman — was a student.

When Nixon invaded Cambodia in April 1970, I joined UNDO, the Union for National Draft Opposition, and was energized by working with students in other classes and members of the community. Through UNDO I met Mike Epstein ’71, who later became my husband. A trip together while working for UNDO turned into 40 years of happiness and a lifelong love of folk music.

It was a heady but turbulent time. The Vietnam War, the civil-rights movement, and the beginning of the women’s and LGBTQ movements stirred emotions. Hope and despair could live side by side. For me it became a time of discovery through interdisciplinary courses and poetry and humanities classes such as “African Folktales,” “Film in American Culture,” and the first women’s studies course taught by Ann Douglas and Nancy Weiss Malkiel. I loved being a pioneer in both film and women’s studies, helping to establish the Women’s Center and writing my senior thesis on “Women in American Film from 1925–1950.” I embraced discovery and change; others found solace in the familiar. Divisions arose, but most of the time we could exchange ideas over a beer at the campus pub, brown rice at the Theatre Intime café, or a cup of Constant Comment tea or glass of Mateus rosé in our rooms.

My interdisciplinary studies became an integral part of how I look at the world. Connecting ideas and connecting people has been an important part of my life, from teaching Nathanael West’s book Miss Lonelyhearts with the film Grand Hotel, to building bridges among people and organizations in my outreach work at public radio and television, to teaching interdisciplinary humanities courses to senior citizens and strengthening community through music. As an alumna, I became active in regional associations, particularly the Princeton Club of Chicago. I helped to start its Women’s Network and organize a celebration of the 50th anniversary of undergraduate coeducation in Chicago last spring. One of my favorite experiences has been serving as a mentor for a Princeton Project 55 fellow. In a life of changes and moves, Princeton has been the one constant from 1969 to today.

Thus many of the people, places, and events of my freshman year helped shape my life. Prospect Garden, a favorite retreat, became our wedding site. Colonial Club, where we had danced to “Sympathy for the Devil,” hosted our wedding reception and Mike’s memorial service. I remember walking by the construction enclosure when Whig Hall was being repaired and seeing a painting of a smiling sun. It reminded me of a folk song used at Mass in those days: “And the morning will see the strolling sun, as he happily rises o’er the land, a messenger on his daily run giving news of a father’s guiding hand, so put away care, let freedom be yours, joy is everywhere.” I couldn’t help but smile as I saw that.

Princeton — its spirit of place and its people — has left an indelible mark on my life. I continue to meet Princetonians who challenge and move me. They have helped me to find out who I am, have enriched my life in so many ways for 50 years, and continue to inspire me to live up to Princeton’s informal motto, “Princeton in the nation’s service and the service of humanity.”

Women of ’73 at a reunion breakfast in 2018, listed in alphabetical order: Ruth Berkelman, Victoria Bjorklund, Melinda Boroson, Arlene Burns, Louise Carlson, Elaine Chan, Maureen Ferguson, Gail Finney, Emily Fisher, June Fletcher, Joan Gallos, Jane Genster, Harriette Hawkins, Robin Herman, Jan Hill, Melissa Hines, Katherine Holden, Ellen Honnet, Robin Krasny, Jane Leifer, Nancy Marvel, Mara Melum, Julia O’Brien, Roberta Pearse-Drance, Beth Rom-Rymer, Diana Savit, Sara Sill, Anne Smagorinsky, Gale Stafford, Nancy Teaff, Lisa Tebbe, Macie Van Rensselaer, Jean Wieler, and Stephanie Wilson

Not Afraid to Be a First

By Tonna Gibert ’73

It was raining in September 1969 when my mother and I arrived on a train at Princeton Junction with several suitcases and my cello. It was the first year of coeducation at Princeton University, and I was a freshman.

We had already shipped a trunk, filled with pleated, wool skirts that my mother bought for me while I was in junior high school — she thought I would grow into them — and had painstakingly hemmed to a more fashionable length.

My mother had made sure that I met her cousin Inez, who lived in Trenton. I had never heard that we had any relatives in New Jersey until I decided to go to Princeton. I realized later that she was giving me an anchor, someone to contact if I ran into any problems. New Jersey was very far away from Illinois — if I needed immediate assistance, no one in Evanston could help me. After a couple of days of getting me settled, my mother made preparations to return to Evanston and leave her 16-year-old daughter alone. A black proctor reassured her: “We’ll look after her, ma’am.”

During those first few days, there were people everywhere: parents and grandparents with college students and their siblings carrying things in and out of dorms. All of the female students had been assigned to live in one dorm: Pyne Hall. My address was easy to remember: 123 Pyne Hall. I had never seen a dorm room before then, but I had my own bed, desk, and storage space. My roommate, a smiling brunette from upstate New York, seemed pleasant. I was ready to begin college and be on my own for the first time in my life.

When I was treated dismissively by my professors or classmates, I wondered, “Is it because I am black or because I am female?”

Classes were held in two formats: lectures in huge lecture halls with resounding acoustics, and small groups called precepts, where students would try to outthink and debate each other. None of the main buildings had enough bathrooms for women — we were an afterthought, and Princeton was not really ready for us. It wasn’t even ready to give us the swim test — thank God. I was usually the only female and definitely the only black student in a precept. As a first-generation college student, many fields of study were foreign to me. I had never heard of philosophy, but I signed up for Philosophy 101. The preceptor marked my paper with a question: “What are you doing in college?” When I was treated dismissively by my professors or classmates, I wondered, “Is it because I am black or because I am female?”

I tried out for the Princeton University Orchestra, confident that I would make it. I had played cello since fourth grade and participated in many musical productions — my high school was known for its spring and summer musicals. I didn’t make the orchestra. “What do I do?” I asked the person who relayed the news. That person suggested joining the community orchestra, but I had no car. I took lessons from a professional musician but eventually stopped playing.

I had been a journalism student in high school, but I didn’t even try out for the Prince. I don’t remember why.

Being around so many unabashedly intellectual African Americans was a novelty to me. In high school, there were usually just two African American students in my honors classes: Harold and me. At Princeton, it was refreshing to sit and talk with (mostly male) black students from all across the United States, Africa, and the Caribbean. I didn’t feel a need to “dumb down” to be accepted, and my ideas were treated with respect.

All of the black people I met at Princeton seemed so much more mature than I was, and definitely more cool. Most of the African American women had Afros (if their hair was kinky enough to bush out), and no one was wearing wool, pleated skirts or plaid dresses. I realized that two pairs of jeans and many shirts would be sufficient. My mother had packed an electric straightening comb, but I had not used it — I had no practice straightening my hair whatsoever. When another black coed offered to cut my hair into an Afro, I jumped at the chance to not risk burning myself or my hair. Within two weeks of arriving on campus, I had an Afro.

At some point during those first days, a white coed invited me to go with her and her roommate to New York to be on the Cousin Brucie show. The show had a live audience, and when we arrived at the makeup room, the makeup people rushed to the other two women and left me sitting alone. During the taping, Brucie asked the other two women if they knew that they were going to get into Princeton when they applied, and they giggled “No.” He asked me the same question; I said “Yes,” and waited for him to ask why. From my high school journalism course, I knew that a follow-up question should be coming. Brucie said, “You did?” and turned to the other two young ladies. He never spoke to me again, even though staff members held up signs marked “Talk to Tonna.”

(The answer to the question never asked: In April 1969, the Princeton admission office contacted my public high school, then rated among the top 10 in the country, to ask if there were any black female students who could do the work at Princeton, as the University was looking for qualified prospects. My counselor informed them of my grades, extracurricular activities, and SAT and ACT scores. “Fine, we’ll admit her,” the admission person responded. “Just tell her to apply.”)

Here are some results of my experiences as a member of the first four-year class of women at Princeton:

I am not afraid to be a “first.” Or an “only.” I was one of the first women in an influx of women entering pastoral ministry in the early 1980s; we attended seminary in pursuit of pastoral degrees rather than religious-education degrees. I was one of the first women to be ordained an itinerant elder (minister) in the Second Episcopal District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church — and the only woman in my class of those pursuing ordination.

I am cautious but open when approaching new situations. Things are not always as they appear at first glance. Sometimes, institutions are welcoming you because you fit a trend, not because you are really valued.

I am not impressed by education or wealth. Both are a result of opportunity and access. Neither indicates intelligence, integrity, or whether someone is an interesting person to know.

I am grateful for the opportunity to have been a pioneer at Princeton. Princeton prepared me to be comfortable in mostly male situations. This has been invaluable to me in seminary and church ministry. I gained a wealth of experiences that I could gain only there and found lasting friendships that I treasure to this day.

Coeducation: One Man’s View

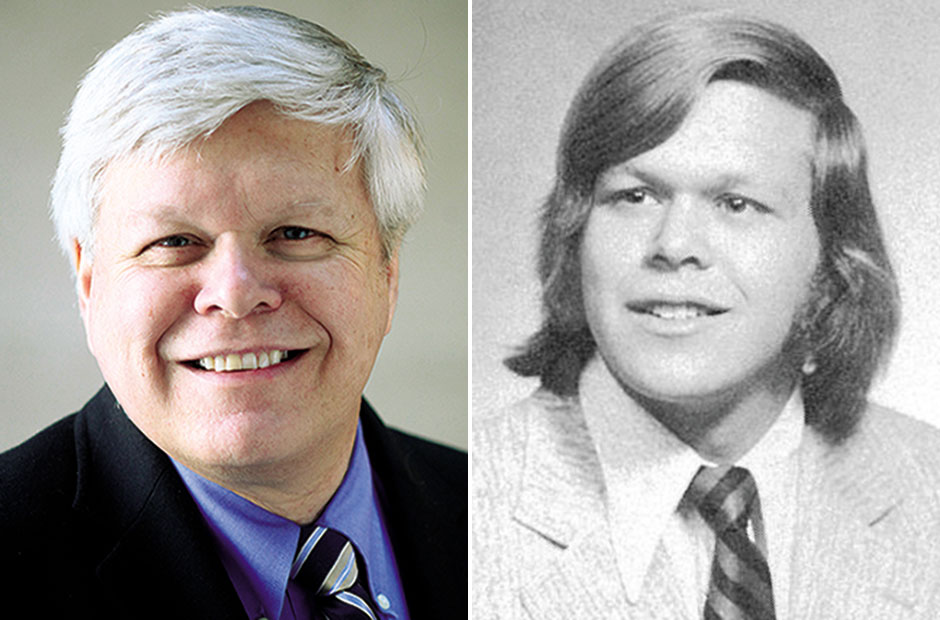

By Gil Serota ’73

The Princeton Class of 1973 made history as the first in 223 years to include freshman women. Sometimes I think people forget that there were male members of that class. There were 820 of us, compared to 101 women. Together, we were then the largest freshman class Princeton ever had.

At every P-rade for the last 40 years, our class has marched behind a large orange banner proclaiming: “Coeducation Begins.” It reminds me that I would not have chosen Princeton if it had not gone coed. I attended a coed public high school in New Jersey. I had no family ties to Princeton and knew no one who had gone there.

As a high school senior, I decided that I did not want to go to an all-male college. My options were expanding almost by the day. By early 1969, Yale, Wesleyan, Vassar, Bennington, Georgetown, and Franklin and Marshall — among others — had gone coed or announced plans to do so. Princeton, however, was undecided. Just before my application was due, the trustees voted to begin to admit women but did not announce a start date. I applied, hoping that the timeline would be sooner rather than later. And it was sooner: They announced in late April 1969 that coeducation would begin the following fall.

Princeton’s timely embrace of coeducation and its stellar wrestling program were the deciding factors in my choice of the University. Once on campus, I learned that not all of my male classmates shared my support for coeducation. Many had strong family traditions at Princeton and would have matriculated in any case. A few were outright hostile to the idea of female students at Princeton. But by the time we graduated, few, if any, expressed any regrets about joining the historic class.

Instead of the social experience I had envisioned, weekends in 1969 and early 1970 felt like they must have been before coeducation.

As we arrived to begin freshman year, I was completely unprepared for the celebrity that was to accompany our female classmates. During the first two weeks of September 1969, Pyne Courtyard became the epicenter of a media blitz. Reporters, television crews, and photographers were stationed all around that dorm, and the women living there had to navigate something of a gauntlet just to go to Commons or to class.

Nor was I prepared for the fact that the small number of women allowed to join our class would have far less impact on my social life than I hoped. The ratio of men to women on campus in late 1969 and 1970 was at least 20–1. So, while I knew I had female classmates and had observed several walking on campus, I cannot recall having a face-to-face discussion with any of them in the fall of 1969. It was disappointing to me that there were no women in the small sections of my first-semester classes. It seemed to me that, as a lowly freshman living away from Pyne Hall, I had about as much chance of having a true social interaction with a female student as I have to speak with Steph Curry when I go to a Warriors game.

Instead of the social experience I had envisioned, weekends in 1969 and early 1970 felt like they must have been before coeducation. Mixers at Dillon Gym included women bused in from other colleges. I dated a girl from Rider College, and my high school girlfriend came to campus for a weekend. My friends and I took “road trips” to Wellesley, Skidmore, and Vassar. I met the first Princeton female I ever dated early in my sophomore year at a Jewish religious service. It was not until my junior year that the growing number of women on campus met the expectations I had for coeducation.

The media followed the changing campus life, as well. About a year after coeducation began, someone left on my desk at the Prince office the front page of The Philadelphia Inquirer featuring a large photo of me and classmate Carey Davis chatting in front of Firestone Library. The picture was set beside the large-type headline: “Studies, Sex Harmonious at Princeton.” The article included nothing about Carey or me. Its highlights were that “sex is no longer a weekend affair at Princeton,” that 20 to 30 percent of female students on campus were cohabiting, and that “the student body is widely described as smarter than those in Princeton’s past.”

During the debate on coeducation in early 1969, an alum wrote a letter to this publication that included the following: “[A] basic requirement for admission ... should certainly be a burning desire to be a Princeton man. He should have decided that he wants to spend four years at Princeton, not four years with girls ... . If he doesn’t feel that way, he should go elsewhere. He will be happier and we will be better off without him.”

I didn’t share those sentiments then, and I certainly don’t now. Last year, at our 45th reunion, I sat under our tent and looked around at our female classmates who had once again returned to campus to celebrate our graduation. Among them were many with whom I developed strong friendships. They were my co-editors and writers for The Daily Princetonian or members of Tower Club, which was one of the first on Prospect Street to go coed. Together, they had a tremendous impact on the quality of life of our class and those classes that followed us. Few can deny that the fabric of our class is strongly interwoven with female thread. I could not imagine it any other way.

3 Responses

Robert E. “Bob” Buntrock *67

6 Years AgoChemistry’s Female Pioneers

In reading the essays in response to the 50th anniversary of undergraduate coeducation (feature, Sept. 11), I was pleased to see a paragraph on the “invigorating” experiences with taking chemistry cited by Lisa Dorota Tebbe ’73. However, I was disappointed when she cited the downsides, including the lack of a women’s restroom in Frick Lab. That surprised me, since all of the secretaries, both in the main and departmental offices, were women. In addition, two female grad students in chemistry entered the Graduate School in 1963. Unfortunately, they left after one year for a variety of reasons.

As a co-educated male all through K-12 and college in Minneapolis, I was disappointed with what I saw for males-only education, both in and outside of the classroom at Princeton. My wife and I were married after my junior year in college, so when I was a teaching assistant and a pair of high heels could be heard walking past the lab on the terra-cotta floor, all 12 of my students swung their heads staring outside the door, and I did too. I went home that night and told my wife about my reaction, and said when we have kids they will be co-educated. She heartily agreed, and our two kids were.

Let me apologize to Ms. Tebbe for the boorish, misogynistic behavior of her chemistry TAs. Let me assure all that not all of us chemistry TAs were like that, and had I (or some of my friends) been her TA, she would not have had bad experiences.

Allison M. McKenney ’75

6 Years AgoTaking Harassment Seriously

I was saddened but not surprised to see the “not-all-men”-style response in R.E. Buntrock *67’s letter in the Dec. 4 issue to Lisa Dorota Tebbe ’73’s reports of sexism at Princeton (feature, Sept. 11). I’m sure that Ms. Tebbe is more aware than Mr. Buntrock of just how many men at Princeton were not like that (probably a lot fewer than he thinks).

But it doesn’t have to be “all men” to make an environment feel pretty hostile. It just has to be most men not doing anything to make it clear to their fellow men that such behavior is unacceptable. I suspect that if Ms. Tebbe did try to report some of the behaviors, no one would have taken it seriously. Women were just expected to put up with it — and still are.

To judge by the article on sexual misconduct (“On the Path to Reform”) in the same issue as that letter, the University culture still doesn’t take harassment and exploitation of women all that seriously. If Mr. Buntrock really considers what Ms. Tebbe went through (and what women in academia, including at Princeton still experience on a regular basis) unacceptable, perhaps instead of writing apologies, he might want to try to change things, such as perhaps actively supporting the women described in the sexual-misconduct article. I’m sure that University officials would be a lot more responsive to those women if they thought that failing to do so might affect Annual Giving.

Norman Ravitch *62

6 Years AgoAfter Coeducation Arrived

In the '50s, students had to import sex workers to the campus and scandal was often caused. After coeducation was allowed, things got more simple. I know few will appreciate my truth-telling.