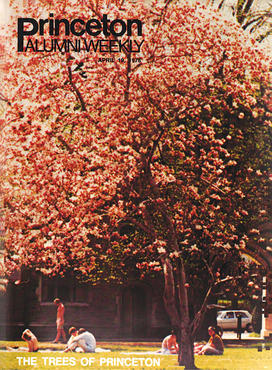

A return to the Princeton campus holds many lessons about the passage of time, and some of the deepest are taught by the trees.

In 2019, I sheltered on a hot day in the shade of a giant white ash near FitzRandolph Gate, waiting with my father, Eric Wohlforth ’54, for his last march in the P-rade before he would enter the Old Guard. I recalled as a child seeing Old Guard members there who had graduated in the 19th century. This tree, as if standing on the edge of a river, had watched them all flow by.

Planted around the time the Marquis de Lafayette visited campus in the 1820s, the tree, which was named for him, remains healthy, straight, and solitary. But not immortal.

According to historian W. Barksdale Maynard ’88, the first generation of trees in front of Nassau Hall, Lombardy poplars, were dying before the planting of this and other native trees. Most of the others from that 1820s planting have died, and arborists now treat the Lafayette tree for the emerald ash borer, which has recently killed ash trees elsewhere on campus and all over New Jersey.

Campus Grounds staff plant 150 to 200 trees a year — not including new trees planted with construction projects — replacing those that succumb to old age, blights and invasive insects, wind and snowstorms, changed land use, and a warming climate. Huge white ash trees that framed Cannon Green were replaced after they died with white oak. McCosh Walk lost some elm and beech trees to the current construction of the new art museum; they will be replanted — just as the row of magnolias on Scudder Plaza was replanted in 2016 after reconstruction of the neighboring buildings.The trees’ lives are long, but the ideas that guide the beauty of the campus have lasted even longer. Early landscapers wanted to maintain open space and planted trees in rows; those patterns continue.

Beatrix Jones Farrand originated the most enduring design concepts for Princeton’s treescapes. Among America’s first landscape architects, she was commissioned in 1912 to plant the new Graduate College. Overcoming sexist ridicule, she realized an innovative design that remains lovely and calming, especially the walled Wyman Garden, with its arbor of European hornbeam (replacing her original lime trees) and a tall hedge of holly trees.

Devin Livi, director of Campus Grounds and a landscape architect, says his crews carefully follow the precepts set down over decades by Farrand, including spending months pruning her signature espalier — trees trained to the walls of buildings like vines — as well as her ivy and wisteria. They grow campus trees in a nursery she established, now located, with her greenhouse, beyond Lake Carnegie.

Livi says his staff of 50 is proud to continue these traditions.

“Everybody knows this is a really special place,” he says.

Landscape architect Glenn “Merc” Morris ’72 agrees. He learned from an early mentor to make character sketches of trees as if they were people, and he enjoys visiting his old arboreal friends on campus. As happens, however, a half-century after graduating, some good friends are gone — trees taken from McCosh Walk by Dutch elm disease, and the enormous European copper beeches below Blair Arch, which were destroyed in an ice storm. But other favorites remain, including a basswood in Mathey College Courtyard that shows up in a photograph taken before construction of the Gothic dorms that surround it.

The tours he gives during Reunions aren’t long enough to show off all the newer areas he loves, especially the “magical” and “exquisite” Shapiro Walk to the Engineering Quad, dedicated in 2001.

“I mean, that’s one of the most gorgeous things they’ve ever put together,” Morris says.

Princeton traditions are deeper than individual trees or people. And they keep growing.

2 Responses

Jim Neely ’48

2 Years AgoEnjoying Dogwoods in 2018

The article on trees was a walk down memory lane. As I am unable to travel from my home in California the tour of the foliage must be passed to our son, ’03, and family. They will walk with the 75th Old Guard honoring my class and me, continuing the Neely family legacy back to 1884.

Five years ago, 2018 we did “go back,” for my 70th, son Robert’s 15th, and a grand-niece, Isabel Neely Hetherington graduating 2018! We took pictures under the dogwood trees and treasure those memories.

Gratitude to all the caretakers of the magnificent trees.

Matthew David Brozik ’95

2 Years AgoIn Service of Humanitree

That 1825 Lafayette ash deserves an honorary Tree-h.D.