Strong Silent Types

Inside the hidden history of secretaries and stenographers at Princeton

In the early 1950s, Miss Caroline Underwood, a secretary with a pleasant, puckish face who dressed in neat wool blazers and skirts, had a very important job at the Institute for Advanced Study. Every day, she would sit at a desk outside professor Albert Einstein’s office and intercept the members of the public who came in to speak with him.

These visitors never had an appointment, but they were often on missions of great importance. They had theories about how to build a perpetual motion machine, or how to achieve world peace, that they believed Einstein would be able to see into being. In a 1952 article, Tiger magazine, which called the visitors “World Savers,” said, “The formula is something like this: World Saver plus World Saver’s Theory plus Einstein equals Utopia.”

When a World Saver came in, which happened up to six times per day, Underwood would smile at them and say, “You’ll have to wait. He’s thinking.” Then she would sit, politely, as immovable as a castle gate, while the World Saver sat or paced and waited for the Great Thinker to finish thinking. He never did. Eventually, the World Saver would tire and leave, another one would enter, and the whole ballet would begin again.

The great age of secretaries, stenographers, and typists at Princeton was the first half of the 20th century, before computers took over clerical work and men learned to do their own typing. The adventures of these knights of ink and paper, who handled the paperwork, found the books, transcribed the correspondence, wrote the drafts of the great papers, and typed the final copies, show us the very human realities of intellectual work. No history of higher education would be complete without them. PAW combed through books, papers, newspaper articles, and correspondence to recover their hidden history.

The bibliographer Roger Stoddard once remarked, “Whatever they may do, authors do not write books.” What he meant was that authors write texts. Books are made by a menagerie of other agents: editors, copy editors, proofreaders, layout designers, typesetters, cover artists, publishers, printers, and, of course, agents.

So it is for scholars. In the days before word processing, scholars didn’t write articles or talks or book manuscripts. Those were typed and even handwritten for them by others, women (mostly) who took dictation or painstakingly turned pages of tangled scribbles into pages of neat type. (Not all of them were secretaries; if you read an academic book that was written before a certain time, you’re very likely to find in the acknowledgments a line of thanks to the author’s wife for typing the manuscript, and sometimes for doing the research, too.)

Which meant, of course, that the scholarly output of the University (and the Institute for Advanced Study, which shared its space and resources) relied on them. Einstein, Inc., so to speak — his scientific and public selves — relied on staffers in and out of Fine Hall. He had assistants to help him with the mathematical aspects of his theories, the last one being Bruria Kaufman, who held a Ph.D. in physics from Columbia. (On her first day as his assistant, Kaufman looked at some formulas that had vexed Einstein for weeks and quickly realized that he had forgotten a factor of two. She hurried to a previous assistant, who assured her that, yes, Einstein could make simple mistakes. “So I got used to the fact that I could correct him,” she later said.)

Einstein’s personal secretary, Helen Dukas, typed up replies to the daily deluge of mail he received at home, which included — for the World Savers were not to be deterred — unsolicited manuscripts explaining their great utopian and scientific ideas. (Sample titles: Sex in Celestial Objects and The Sun Is Not Hot.) And to produce his scientific papers, he made free use of Fine Hall’s secretaries, whose duties included typing handwritten papers so they could be submitted to journals.

The mathematician Herman Goldstine, who worked in Fine Hall, later observed to a University historian that, regardless of how fast or slow inspiration lit bonfires in scholars’ brains, the advance of science actually proceeded on the schedules of three secretaries: Agnes Fleming, Helen Johnson, and Gwen Blake.

“So there would be Veblen and von Neumann and Einstein and Alexander and Weyl,” Goldstine said, “all these people would be in a queue waiting with these monumental papers to get them typed.”

Agnes Fleming was the principal secretary of the mathematics department; Helen Johnson was the secretary of the University’s physics department; and Gwen Blake was the secretary of the School of Mathematics at the Institute. Alongside their regular duties, they were used by scholars as a typing pool to produce finished papers that could be submitted to journals. For this they were paid some 60 cents per hour in addition to their paychecks as secretaries. (In its early years, before it moved to its own campus, the Institute resided in Fine Hall and shared resources with the University.)

Florence Armstrong was another secretary in the mathematics department who did typing; in mathematics, a typist had to master all kinds of arcane symbols. A number of students thanked her for typing their dissertations — as here, in the thesis of Charles Fefferman *69, later a Princeton professor and winner of the Fields Medal: “Thanks, finally, to my typist Miss Florence Armstrong, by whose prodigious cryptographic feats, my manuscript was transformed into something readable.” During World War II, Armstrong worked with the Frick Chemical Laboratory on a secret aspect of the Manhattan Project, for which she got a lapel pin after the war. (They were exploring the possibility of heavy water as fissionable material. The Manhattan Project ultimately went with plutonium and uranium.) She retired in 1971 after working in the department for 27 years.

How much typing did a Fine Hall secretary do? In 1937, the mathematics department had an annual budget of $1,000 to spend on typing and printing. This covered not only the typing of individual scholars’ papers — and this in one of the most productive departments in the country — but also types of scholarly production that didn’t exist at other departments. For example, Blake and her colleagues typed, mimeographed, and distributed what was called, informally, the Princeton Mathematical Notes: lecture notes from courses taught in Fine Hall. Between 1933 and 1938, they put together some 30 volumes of the series, with some 20 courses to a volume. As word about the Notes spread, scholars at other universities requested copies, until finally Blake, as the Princeton mathematician Albert Tucker recalled, “was spending about half of her time taking care of the correspondence that had to do with the Notes.” (In 1938, Princeton University Press took over publishing the Notes, relieving her aching hands.)

The typing was paid as if it was optional, but the secretaries weren’t allowed to treat it that way. In 1936, Blake wrote to Abraham Flexner, the head of the Institute, that every summer she felt overwhelmed with papers to type while the other secretaries were on vacation. Flexner replied that the Institute was a guest in Fine Hall, so to avoid creating the impression of bad manners, Blake should make sure the typing for all of Fine Hall’s departments got done, no matter what difficulties arose. And she should do it without making extra claims on that $1,000 fund. Flexner closed the letter by advising her to work something out with the other secretaries and adding, “I assume that there is no financial obligation involved whatever the arrangement reached.”

“When everybody else was going nuts, she would be quite calm and say, ‘Well, maybe we just ought to talk more about this.’”

— Howard Taylor, former professor of sociology on Hattie Black, a secretary who worked at Princeton for more than 50 years

The department took great care in selecting secretaries, just as it did in selecting professors. Solomon Lefschetz, a math professor who had administrative oversight of the department’s research, seems to have had a hand in selecting many of them. Fleming, for instance. The daughter of Irish immigrants, she started working at the University at 18, following the path of many girls from the local high school who took part-time jobs as stenographers. Lefschetz liked her work and got her a permanent job in his department. She served as a secretary there for more than 40 years, retiring in 1972 at the age of 60. (“She had an excellent memory,” Tucker later said. “Her memory was sort of the file for the department.”)

In a very real sense, the work of a Fine Hall secretary was never done. Their task, after all, was to regularize the very irregular workflows of mathematicians, to transform a maelstrom of chaos and caffeine into a factory that produced finished papers. The mathematician Alonzo Church, for instance, used to do his work in Fine Hall overnight, sustaining himself by drinking a remarkable concoction mixed together from all the milk and cream and tea left over from the daily Fine Hall tea. The next morning, Fleming would discover Church’s handwritten papers on her desk, jotted over with colored pencil to show where special symbols and the like should go. Even after a researcher’s death, the work of his amanuenses continued. After Einstein died in 1955, Bruria Kaufman helped his friend, the mathematician Kurt Gödel, to clean out his office and presented the final paper he ever wrote, on which she was co-author. Helen Dukas took care of his personal papers until her death in 1982.

Secretaries in other departments had labors no less Herculean. In 1948, PAW remarked on the perpetual tumult in the offices of the English department: “Mrs. Jane Birch, her aide-de-camp, Mrs. Gloria Donaldson, and the department’s able battery of secretaries, are busy as Wordsworth’s bee with the multiple tasks of typing and mimeographing letters, reports, instructions, notifications and lecture outlines; keeping departmental and course records, relaying local and long-distance calls to the proper auditors, distributing mail, checking class lists and grades, and serving as receptionists to questioning students, book salesmen, publishers’ representatives, visiting professors, or (during the war) even to occasional FBI operatives.”

One definition of a secretary, in short, is someone who has seen it all. But at a university, even if you’ve seen it all, people still find ways to surprise you. In 1957, The Daily Princetonian reported that Birch, who by then had served the English department for 20 years, was recently caught off guard when a senior brought in a thesis bound with parchment, pricked his finger, and signed it with his blood. (After graduating, he became a novelist, she said.)

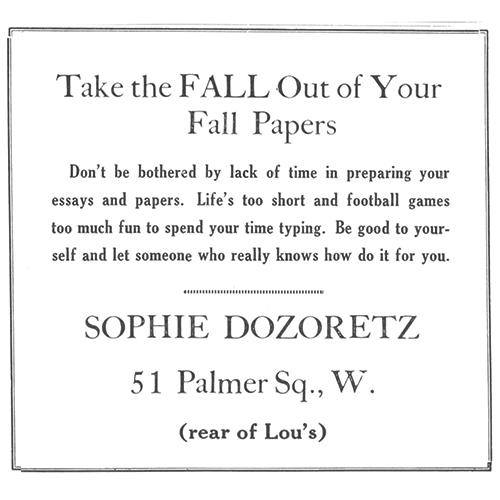

Like the professors, students at the University often hired typists to produce submittable copies of their papers. (And readable copies of their own notes.) The Prince published ads daily from freelance typists who lived in town. (The ads showed just how astutely the typists understood their student clientele: “Don’t be bothered by lack of time in preparing your essays and papers. Life’s too short and football games too much fun to spend your time typing.”) For students who preferred to dictate their immortal ideas rather than waste time writing them by hand, the Nassau Stenographic Shop, located above a much-loved lunchroom called “the Balt,” was ready to serve. Township newspapers, meanwhile, published ads from the University seeking typists, stenographers, and secretaries to help with critical scientific work.

Most of the typists and stenographers at Princeton were women. In fact, the typewriter was a woman’s instrument from the start: When it was invented in the 1870s, its novelty meant it offered women a field of work that wasn’t already male-dominated, and they wound up defining the field instead. Early on, businesses often rented out typewriters with women who were able to use them, also called “typewriters” (later, typists), attached. Employers embraced the technology because women were paid less than men, making typewriters and their typewriters a money-saving combination. (As always, ideology followed economics: The claim went out that women made better typists because their “natural dexterity” gave them an advantage.)

The typing and stenography pools, in which the University tried to keep a ratio of one typist for every five researchers, sought to give faculty an alternative to waiting in line for the help of department secretaries. This meant that every now and then a bemused civilian would find herself taking dictation for Einstein — which is what happened to Lietta Shearer, an 18-year-old who worked as a stenographer in the University’s science division.

One day in 1941, Shearer received a summons to the Institute for Advanced Study, where, that same evening, Einstein was to give a talk for the American Physical Society, titled, “On Solutions of Finite Mass of the Gravitational Equations.” She told the Associated Press that he was a very clear speaker: “The feature that struck me the most was that, while he had no notes, every statement was a complete thought.” (Like many scholars, he had a pet phrase — in his case, “infinitesimally small.”)

In 1942, the Associated Press published an article about the encounter — a light color piece about a teenager meeting the great Albert Einstein. The way they chose to cover it, however, was both conventional and loutish. Shearer wasn’t there to pose for a pinup poster, but the piece still begins with a wolfish description of her looks: “Consider the pretty blonde stenographer … the slender, blue-eyed girl recalled … .”

Here, an old and unfortunate trope about stenographers and secretaries: Not just that they were unnecessarily sexualized, which has been true since women started entering clerical work around the time of the Civil War, but the subtle maneuvering that gave them the blame for it. Just a moment’s thought would show how silly it would be to sexualize Einstein himself in this way: to lead a piece on the physicist with a description of his wanton hair, his devastating wool sweater, and, at the terminus of his pretty legs, a lack of socks (Einstein thought they were a waste of time) that showed off his well-turned ankles.

We may hope that the faculty refrained from such affronts, but the students didn’t always. In 1932, the staff of the Prince added suggestive language to a typist’s ad that they forgot to remove before publishing it. The ad in the paper said, “SOPHIE DOZORETZ … Now for Myself at — ROOM 315, 20 NASSAU. Hours — 9 to 5 and later by appointment. P.S. — If you are too lazy to sit down and write it, come up and dictate it to me. I’m pretty too!”

A few days later, the paper published a correction: “The Princetonian wishes to apologize for an error made in the advertisement of Sophie Dozoretz, typist. The phrase, ‘I am pretty too,’ was erroneously inserted.”

Universities, like trees, are entities of both stability and change. Year by year, the students come into leaf and scatter; the faculty pick up and move to other schools, like maple seeds spinning on the wind; the rings of the trunk slowly widen as the campus adds new buildings. Meanwhile, the arteries and veins, pervasive and persistent, circulate the moisture and nutrients that keep the tree alive. Secretaries often stayed at Princeton longer than the faculty, longer than administrators, longer than anyone else.

In 2002, Hattie Black, a secretary in the Program in African American Studies, was celebrated for passing the half-century mark at the University. Black started at Princeton in 1951, when she was 17 years old. She, too, came from a local high school, where she heard that the department of geology needed a typist and successfully applied to join the department’s typing pool. In time, she became a department secretary. In 1972, she moved to the Program in African American Studies, where she did everything from handling finances to advising students to counseling professors on course syllabi. Howard Taylor, a professor of sociology, described her as the program’s steady core: “When everybody else was going nuts, she would be quite calm and say, ‘Well, maybe we just ought to talk more about this.’”

An account of Black’s years on campus would be a history in miniature of the American century. She saw Einstein on his walks across campus, shook hands with Martin Luther King Jr., and watched in 1969 as moon rocks arrived in Guyot Hall to be studied. The first women students arrived on campus; students protested the Vietnam War, carrying banners that declared, “EVEN PRINCETON”; computers shrank, multiplied, and crept across phone lines. By 2002, students were hooked on AOL and Napster.

“I can’t believe I’ve been working here 50 years,” she said then. “The time has just passed so quickly.”

Starting in the 1970s, the new technology of word processing slowly made typing pools obsolete. More and more, scholars did their own typing, since the ease, on a computer, of making changes on the fly made it worthwhile to learn how to type. By the end of the century, department secretaries focused entirely on administrative duties, which included working the arcane reaches of the University’s computer systems. Their job title, too, had changed to administrative assistant.

And yet, though their name and responsibilities have changed, administrative staff remain the most essential members of their departments. To this correspondent, they are the terrifying old gods of a university, the ones who can make exceptions to rules, bring the most arrogant professors to heel, remember the origins of the department’s strangest policies, and use administrative privileges to do things in the computer system that no one else can. Anyone who has the pleasure of knowing them, or the displeasure of displeasing them, understands the power of their presence.

The importance of Caroline Underwood’s job as a barrier between Einstein and the public may be explained, in part, by an incident in 1952 when a man walked into an office at Columbia University and shot the secretary of the American Physical Society, killing her. He had been writing to the society to explain his theory about how electrons could be used to make humans “live forever,” but nobody answered his letters, so he entered Columbia’s campus that day with a plan to kill as many physicists as he could, thus bringing attention to his cause. (“It was my book,” he later told police. “They wouldn’t look at my book. They wouldn’t even look at it.”)

The secretary, Eileen Fahey, wound up being his only victim. It wasn’t her job to be in the way of that bullet. But administrative staff oversee every meaningful gateway of the university, which means that when conflicts arise, whether among faculty or students or between the university and the public, they are, so to speak, on the front lines.

Today, we are the heirs to a world they made, though we often overlook their omnipresence. It’s curious how many histories of higher education, of the great discoveries and famous papers, have been written by those who looked at the historical records, the pages of typed lecture notes and book manuscripts and dishy correspondence — and forgot, precisely, who wrote them.

Elyse Graham ’07 is a professor at Stony Brook University and author of the recently released Book and Dagger: How Scholars and Librarians Became the Unlikely Spies of World War II.

0 Responses