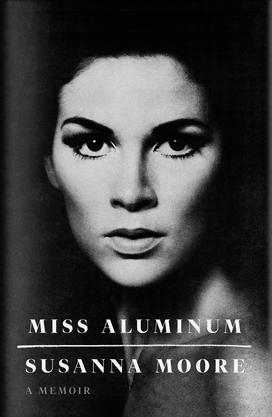

Susanna Moore Tells The Story of Her Glitzy, Yet Dark Life Journey

From New York to Los Angeles, Moore recounts how she worked as a model, and meeting several notable celebrities of the time, such as Joan Didion, Audrey Hepburn, Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson. But beneath the glitz lay an ambitious hunger to learn and her tortured efforts to understand her mother’s death. Moore offers a cutting but comical portrait of Hollywood in the ’70s, and of a young woman’s strident effort to find her herself and her place in the world.

The author: Susanna Moore is the author of the novels The Life of Objects, The Big Girls, One Last Look, In the Cut, Sleeping Beauties, The Whiteness of Bones, and My Old Sweetheart, and the nonfiction works I Myself Have Seen It: The Myth of Hawai‘i and Paradise of the Pacific: Approaching Hawaii. She lives in Hawai‘i and teaches at Princeton University in the creative writing program.

My grandmother lived with her unmarried daughter, my Aunt Mary, in a working-class neighborhood in North Philadelphia called Germantown, inhabited by first- and second-generation Polish, German, and Irish families, in the same small battered house where, as a young widow, she had raised her five children. In the front room, sitting on a rusty radiator, was a chipped plaster statue, two feet high, of the Infant of Prague, for whom she had made a billowing red faille cape with a high, stiff collar, stuffing the interior of his gold-plated crown with the same material, and two brocade gowns, a white one for Holy Days and a cream-colored one for days less sanctified, each with lace collar and cuffs.

In addition, there was a console with a television and a radio, my grandmother’s chair, a few rickety tables with yellowing crocheted runners, and a sofa. The wall telephone was in the kitchen, which always smelled faintly of gas. I was given a small bedroom on the second floor, overlooking a neglected yard. We shared a bathroom that smelled of cigarettes and starch, as my aunt used the tub to wash her nurse’s uniform. A large rusty fan was wedged into my grandmother’s bedroom window to cool the house in summer.

My grandmother and her younger sister had immigrated to Philadelphia in 1910, when Mae was nineteen years old. She considered her undeserving self to have been especially favored by the Virgin, whom she thanked every day of her life, as she had soon found work as a housemaid and seamstress for a rich family in Chestnut Hill. My grandfather, Dennis Shields, was chauffeur to the same family, and in the photograph that my grandmother kept next to her chair for fifty years, he wears a peaked cap, a high-necked gray wool tunic, jodhpurs, and polished black boots. He died during the Depression, perhaps from the effects of gas suffered in the First World War, in which he served as an ambulance driver in the Army of the United States, earning a citation for conspicuous bravery under fire.

My mother, whose name was Anne, liked to say that Mae had been a lady’s maid, a position that demanded more refinement than was customarily found in a house servant. She was eight years old when her father died, and claimed that after his death, she and her younger brother and sisters were each given only an orange on Christmas morning. When she was eighteen, thanks to the intercession of the Infant of Prague, she received a navy gabardine suit and a gray tulle evening gown, hand-me-downs from Mae’s Chestnut Hill employer, which allowed her for the first time to imagine that she might one day create herself anew.

Clothes, which provided the means both to conceal and to display herself, became objects of fetishistic importance to my mother. It was, after all, the well-made suits and evening dresses, tailored to fit her, as well as my grandmother’s insistence that her daughters learn Main Line manners and customs, that had, with some sleight of hand, transformed my mother from a shanty Irish girl into a beautifully dressed and well-behaved debutante. This is not to suggest that my grandmother and my mother had a calculated and well-thought-out plot to facilitate my mother’s escape from Germantown, but rather that they knew, at least my grandmother knew, to make the most of what they had been given.

My father, an intern in medical school, had grown so enamored of the lovely student nurse who was to become my mother that when he at last learned that she was not a girl from the Main Line, it was too late. By the time I was a child, she had become the woman she wished to be, and was no longer playing a part, only now and then hiding behind an unfortunate and even unnecessary lie, as when I heard her gaily tell a neighbor that she had attended Bryn Mawr, causing the woman to ask in delighted kinship, “Oh, my dear, did we know one another? Who are your people?”

My mother was ashamed of her impoverished Irish Catholic childhood, and the story of the Christmas orange and other childhood sorrows were told to me in a whisper. As she was given to exaggeration, I did not always believe her, suspecting, too, that I was not always meant to believe her. As a bride, she had been treated badly by my father’s family, the descendants of Quaker farmers and wheelwrights and millers, acquisitive and narrow-minded, who had come to America in 1633 with William Penn, settling west of Philadelphia in Chester County. Over time, they had lost their thousands of acres at Chadds Ford and Newtown Square, as well as their austere religious practices. They had as dissenters so proudly answered only to themselves that they had lost the gift of tolerance, considering themselves superior to those whose suffering appeared less sublime in origin; fleeing tyranny, they did not hesitate to practice it themselves. In the eighteenth century, some of my ancestors had been expelled from Quaker meeting houses for marrying Protestants and, even more damning, the occasional Irish indentured servant. One of them, a blacksmith, was disowned for shoeing a war horse. It had been as impossible for my mother, given her experience of poverty and humiliation, to feel kinship with my father’s family as it had been for them to embrace a girl who, being Irish and Catholic, was assumed to be dishonest, dirty, and ignorant. My mother, at least in the beginning, was occasionally dishonest, but she was never dirty.

* * *

WHEN I WAS twelve years old, my mother, then thirty-five years old, died in her sleep. My Aunt Mary immediately took leave of her job as head nurse in the emergency room of Pennsylvania Hospital and made the long trip to Honolulu.

My aunt was tall and slender. Her black hair, already turning gray, was kept in a neat bob that reached her chin. As she was from that mysterious place called the mainland, she wore short white kid gloves to Mass on Sunday. She used a dusting powder from Elizabeth Arden called “Blue Grass.” There was a prancing horse on the lid of its round box, and its scent mingled with the strong smell of her Chesterfield cigarettes. My mother had been spirited and funny, even mischievous, and I was surprised to discover that despite my aunt’s appreciation of wit, she was a bit prudish. She would turn away when I changed my clothes in her presence, which was fine with me, but not a gesture to which I was accustomed. I noticed, too, that she was a wary and fretful driver, refusing to make a left-hand turn in an intersection, a habit that added fifteen minutes to any drive, and which lasted for all of the years that I knew her.

There was immediate tension between my aunt and my father, evident in her expression when he appeared to take things too lightly, and in his refusal to acknowledge her disapproval. Her role as caretaker to her dead sister’s children was not clearly defined and must have at times caused her to feel like a servant, a role that held a certain shame, given her mother’s former employment. My aunt’s displeasure increased when my father soon began to behave as if he were a bachelor, content to leave his five children, the youngest only two years old, in her dutiful care. He went out to dinner most nights and sometimes returned late, which naturally offended my aunt, who, like me, must have been listening for him. His name was Richard Dixon Moore, a radiologist, forty years old, good-looking and charming, with the distinction and social position then conferred on doctors in small cities and towns. I knew that my father was fond of women, and his recent bereavement did not appear to have lessened his interest. That he had many children at home seemed not to bother anyone but Mary. A neighbor once hinted that my aunt was jealous, but my aunt was so unlike my father, who was pleasure-loving and weak, that even as a child I understood that something as seemingly simple as friendship between them was impossible. It is also likely she blamed him for my mother’s death.

He would sometimes take me to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel on a Sunday night. I would order decorously, a little shyly, even when he encouraged me to try things unknown to me like chicken Kiev or peach melba. His own eating fascinated me. It seemed to me very old-fashioned, habits perhaps inherited from his Quaker ancestors—radishes with butter, cheddar cheese on apple pie, salt on cantaloupe.

In anticipation of these evenings, I found a tube of Tangee lipstick at Woolworth, soft orange wax in a flimsy metal tube, which I wore for a dinner concert given by the Kingston Trio at the Royal Hawaiian. It had a very cheap, sweet smell and I don’t know how my elegant father tolerated it, but he never said a word, certainly not the compliment I hoped I would receive. I wore one of my full-skirted, tight-waisted Lanz dresses, with a stiff crinoline that scratched pleasantly against my legs. My father’s attention, which had been amiable but distracted before my mother’s death, could not have come at a more precarious moment in my life, but I did not know that. There I was in my lovely dress, happy in my prettiness and eager to please my father, yet all the while thinking in a vague, flitting way, Be careful, don’t like this too much. You are here because your mother is dead.

After one of our Sunday night suppers at the Royal Hawaiian, my father gave me my mother’s pearls, and an amethyst ring, large and rectangular, set in gold, known, rather glamorously I thought, as a cocktail ring, with the admonition that I was not to wear it or the necklace until I was older. I once wore the pearls to bed, but I was so afraid that the strands would break that I couldn’t sleep, and I never did it again. I was able to wear the ring on my middle finger if I wrapped a Band-Aid around the back of it, but only in my room and at night, my hand heavy with the weight of it. The necklace and the ring were my only souvenirs of my mother, other than a shoebox of photographs that I had taken from my father’s desk and kept hidden under my bed. One day, however, as I left the house, I pushed the ring onto my finger, and then my hand into a pocket of my shorts so that no one would see it. I walked the mile to the bus stop at Lunalilo Home Road where Mr. Silva, the bus driver, stopped for me. We traveled past Kuli‘ou‘ou and Niu Valley and ‘Aina Haina before Mr. Silva handed me my paper transfer and I boarded the bus waiting at the roundabout at Star of the Sea church for the rest of the trip, through Kahala, past Diamond Head and Kapi‘olani Park into Waikiki. The ride was a pleasant one, the bus plump and jolly like a bus in a cartoon, with open windows and leather seats. My hand was no longer in my pocket, but rested, somewhat awkwardly, wherever I thought someone might notice it, and admire it.

I left the bus at Kalakaua Avenue and crossed the street to the Outrigger Canoe Club for my weekly surfing lesson with the beach boy, Rabbit Kekai. I changed into my new white sharkskin two-piece bathing suit and went to meet Rabbit. As I was afraid that I would lose the ring in the water, I asked the man on duty at Beach Services if I could leave it with him. He handed me one of the small brown envelopes people used to hold their keys and money and wrist watches when they were on the beach, and I put the ring inside the envelope and sealed it and wrote my name on it.

Review: "As readers of Moore’s fiction know, she is a brilliant storyteller and sentence-maker … [Miss Aluminum] reminded me of everything I ever loved about her as a writer and now, as happens with certain memoirs, I feel like she is my friend — a very elegant, accomplished grande dame sort of friend, to be sure, one who might loan you a pair of blue velvet Pucci bell-bottoms or a copy of The Great War and Modern Memory on your way out the door after tea." —Marion Winik, The Washington Post

No responses yet