The symbolic center of Princeton

A new exhibition shows how the Faculty Room has reflected the University’s history

The first time Karl Kusserow was in Nassau Hall’s Faculty Room, a large group of visitors walked in, and he was struck by their reverential reaction.

“The weight of the past is very present here,” said Kusserow, associate curator of American art at the Princeton University Art Museum.

That effect inspired the exhibition “Inner Sanctum: Memory and Meaning in Princeton’s Faculty Room at Nassau Hall,” running from May 28 to Oct. 31. The show explores the room as the symbolic center of the University, the history of the room itself, and how the space and the portraits reflect not only the evolution of the University and its history but also broader socio-cultural trends.

Located in the Faculty Room, the exhibition will be open to the public Friday and Saturday of Reunions from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Beginning June 2 it will be open Tuesdays through Saturdays 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Sundays 1 p.m. to 5 p.m.

The Class of 1970 funded “Inner Sanctum” in honor of its 40th reunion. [The exhibition is a project of the University Art Museum.]

Lighting in the room has been improved, and protective glass has been removed from the portraits. On display in the center of the room will be information about the portraits, the room’s history, and archival photographs.

The Faculty Room was severely damaged by two major fires in the 19th century and rebuilt, doubling in size after the second one. The room originally served as a prayer hall, before briefly becoming a portrait gallery, then a library and a museum. Finally, Woodrow Wilson 1879 turned it into the Faculty Room in 1906 — drawing inspiration from the British House of Commons. The room’s changing uses reflect the University’s progression from a religious orientation toward a more humanistic tradition. Ultimately the space was “dedicated to the institution itself,” said Kusserow. Today, it is used for faculty and trustee meetings and as a stop on the Orange Key tour.

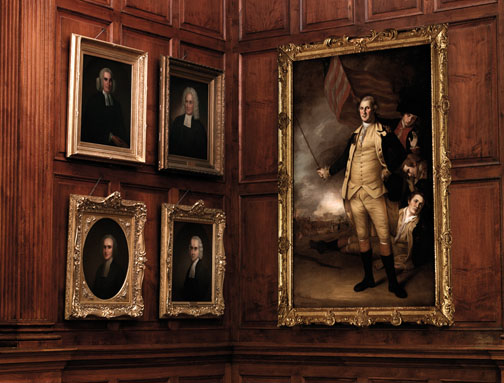

Portraits have hung in the room since 1761, but the aesthetic quality of the 33 paintings of Princeton’s founders, leaders, and distinguished alumni is mixed, Kusserow noted. For example, hanging next to the portrait of “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton,” an icon of American art by Charles Willson Peale, is a portrait of President Samuel Davies, which was painted by a little-known artist from a photograph of a print believed to depict the long-dead Davies.

Nearly half of the frames have been restored, including the one holding “George Washington at the Battle of Princeton.” The painstaking, yearlong restoration of that 1761 frame (which originally held a portrait of George II before it was famously “decapitated” by a cannonball that sailed through a window of the then-prayer room during the Battle of Princeton) involved using dental tools to pick out “centuries of accumulated crud,” Kusserow said.

Accompanying the exhibition is a catalog with essays by Kusserow and faculty members, including professor emeritus and novelist Toni Morrison, historian Sean Wilentz, religion and African American studies scholar Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97, and poet Paul Muldoon.

No responses yet