A Talk With Princeton’s Lawyer About the Honor System

University Counsel Thomas H. Wright Jr. ’62 looks at the increasing number of law suits being brought against American colleges and considers how it is affecting the way they carry out their educational mission.

In recent years American colleges and universities have seen a spectacular increase in the number of law suits brought against them by dismissed faculty members, failed or disciplined students, and others. To cope with this rising litigiousness, most institutions have appointed lawyers to their administrative staffs. Further, a new body of “education law” is now being taught at several law schools; textbooks are rolling off the presses with titles like The Law of Higher Education, College and University Law, Higher Education and the Law; and there is even a quarterly Journal of Law and Education, founded in 1972.

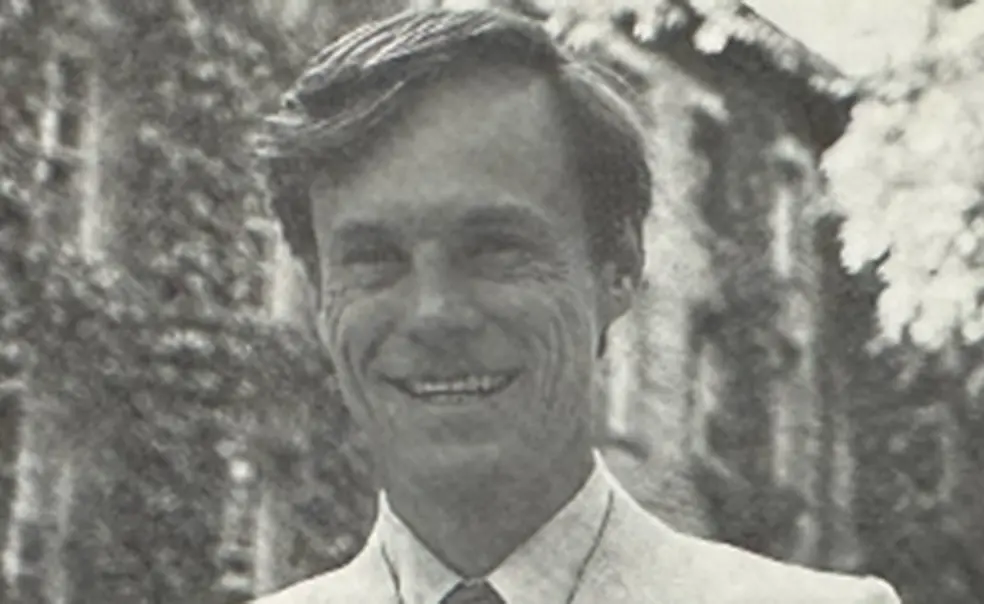

How is all this affecting the way colleges and universities — particularly the private ones, whose traditional freedom from outside interference has been a prized characteristic — carry on their affairs? For insight into this question, we called on Thomas H. Wright Jr. ’62 (Harvard Law ’66) who nearly a decade ago became Princeton’s first University Counsel. At 41, slim and fit-looking, Wright speaks with an uncommon combination of lawyerly precision and youthful enthusiasm. Seated at an old walnut, book-stacked conference table in his third-floor Nassau Hall office, he leaned back in his chair and began by briefly describing three suits in which Princeton is currently involved and which he feels are especially significant:

“The first is that of an undergraduate who two years ago was suspended for one year — he is now back on campus as a junior — because the all-student committee that administers Princeton’s 88-year-old Honor Code found him guilty of cheating on an in-class quiz. President Bowen, appealed to by the student, upheld the committee’s decision, and the student is now suing Princeton for $500,000 and a clearing of his record on the grounds that (1) the particular result of the Honor Code process was erroneous; (2) its procedures were unfair; and (3) at its most basic level the Princeton Honor System is against the public policy of the State of New Jersey because it grants too much power to students who are not mature enough to be trusted with it.

“The case is now in the pre-trial ‘discovery’ phase, wherein each side rummages around in the other’s files, on the theory that the better each understands the other’s case, the more likely they are to settle before trial, or to have a fair trial. Depositions are being taken on both sides. Documents ranging rather far afield have been requested by the student’s attorneys, who have also asked the university to respond to long lists of questions. We in turn have submitted long lists of questions to them. This is now going on at a lively rate. Both parties tend to resist queries, so there have been ‘motions to compel’ the disclosure of further information by one side or the other, and there are time-consuming hearings in court on these motions.”

Wright is closely involved in and has overall responsibility for Princeton’s defense, with the help of an outside attorney, or “litigator,” William Brennan III of Princeton, who will be the trial lawyer if the case goes to court (but would have to drop out if it got to the U.S. Supreme Court because his father is an associate justice).

“The case is significant in part because if the university were to lose it, any student found guilty of cheating in the future, and penalized for it under the Honor System, might feel he had a fair chance of collecting damages, and this could lead to many more suits.” And possibly to the end of the Honor System? “Possibly. On the other hand, if the courts say the university handled this situation well, it would tend to preclude further litigation of this particular kind.” If not settled beforehand, the case will be tried in the Federal District Court of New Jersey because, though the student is suing under New Jersey law, his home is in Maryland, making it in effect a federal case.

“And by no means incidentally in this day of tight budgets, the case is significant because it is proving expensive in university administrators’ time — President Bowen has already spent a day in deposition with the plaintiff’s lawyers — and in fees paid to the litigator, who, even though the case may never come to court, has to have control of the defense from the early stages.”

Significant case number two “is not actually a law suit at the moment, but could easily become one and therefore must be handled as one. In it, a former woman faculty member complains that in denying her promotion two years ago the university not only acted unfairly against her but that this was part of an illegal pattern of discrimination against women faculty at Princeton because of their sex.” On the day of our interview, her charges were before the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) but could become the basis for a law suit regardless of how the EEOC rules.

What makes this case more sensitive than other similar ones the university has faced is the “pattern” charge; that is, explained Wright, the claim “that the structure and procedures of the committees that recommend and approve faculty appointments and promotions have an inherent ‘systemic’ or ‘systematic’ — both terms are used in such complaints — bias against women. This would make it a class-action suit if it came to court. She also calls our grievance and review process inadequate.” There is an outside litigator in this case, too — Henry T. Reath ’42 of Philadelphia — who will represent the university if it gets to trial.

“Before the former faculty member filed her complaint, a university faculty committee had reviewed her charges of unfairness in regard to her failure to receive a promotion, and had concluded that they were unfounded.” Since she raised the broader (“systemic”) questions, another faculty committee has been conducting an intensive review of them. “On these broader questions, we have taken the position — before the EEOC, and we would do so in court — that Princeton’s hiring and promotion procedures clearly meet applicable legal standards and, beyond this, that suggestions for improving these procedures should be principally subjects for the faculty rather than for the courts to consider. There is, after all, virtually nothing in the university more sensitive and important to it than how faculty members are selected, and how the faculty as a whole is shaped over the years.”

Wright’s third significant case “has Princeton in the role of ‘intervenor,’ that is to say, a ‘highly interested third party,’ in an action brought by the State of New Jersey against a representative of the U.S. Labor Party who came on campus in the fall of 1978, solicited memberships and sold copies of printed materials in violation of a university regulation denying outsiders the right to do that without permission. He knew of the regulation because he had earlier complied with it, and then violated it after being warned that his violation would subject him to arrest by local police under a state law against trespassing on private property.”

The state’s case — i.e., the university’s right to make its own rules as to access — was upheld in Princeton Borough court and in New Jersey Superior Court, but it lost in the State Supreme Court. The university and the state, with Nicholas deB. Katzenbach ’43, former U.S. attorney general and a Princeton trustee, primarily responsible for the appellate argument, has appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which will hear it next fall.

Princeton has been criticized by some of its own faculty and students, among others, said Wright, for “appearing to be opposing freedom of speech, one of the most basic principles of higher education, and it’s painful for a university to be in a position thus misunderstood. But I’m convinced that at the level of long-term principles we are making the right argument. The issue in the case is not what should be Princeton’s particular rules regarding access by outsiders — we and the defendant are now in substantial agreement about that — but rather who should make those rules.

“The New Jersey Supreme Court has said that it will determine what is reasonable access to the university’s campus, by reviewing the educational goals of the institution and measuring those against the reasons particular outsiders want access. In our view, that kind of content-related determination of ‘reasonableness’ is exactly what the state is forbidden from doing under the First and Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which we believe protect a private university as much as an individual rom state interference of this kind. Put another way, the case can be said to pose the question whether institutions like Princeton are protected by the First Amendment or are — like governmental entities — restrained by it. Few things could be more important to us in the long run than being on the right side of that line.”

The Association of Independent Colleges and Universities in New Jersey has filed an amicus brief in support of Princeton, as has the largest national education association, “so it’s a case whose disposition by the Supreme Court will be closely watched.” Wright’s legal position on this case, as well as his sensitiveness to student opinion on it, were revealed in a long, detailed letter he wrote to a woman student who had charged in the Daily Princetonian that the university was “violating the Constitution” by denying free access to the campus. He tactfully pointed out that private individuals and private institutions, acting as such, cannot, in fact, violate the First Amendment “which exists to constrain government” and “to protect the freedoms” of private parties against government encroachment.

Wright would refer back to these three cases, but he stopped there to generalize, saying, “There is an enormous difference between today and 25 or even 10 years ago in the readiness of people to take their grievances — including those against universities — to court. The hospitality of the courts to such cases is of course not unlimited — many do not come to trial — and universities tend to win those that do; but the frequency with which they are being brought is alarming in terms of expense to the institutions, and, perhaps more important, because of the way that it can influence faculty and administrators to keep looking over their shoulders as they make decisions.

“Some of this may be healthy, may contribute to the making of fairer decisions, and obviously the courts should be available to correct injustices. But it’s a question of degree. An individuals’ own sense of responsibility can be undermined if he knows there is a readily available resort beyond him. He may avoid hard decisions, pass the buck, knowing his word will not be final anyway, and that he may have to spend a lot of time, in a not necessarily understanding forum, defending what is, in any event, a close or difficult case, or a largely subjective judgment.”

Does Princeton have more to lose from this new litigiousness than do other major research universities?

“I think in some ways we do — though other universities certainly have serious problems we don’t have. Those with medical schools, for example, find them a particularly rich source of legal headaches. They operate hospitals and are subject to medical malpractice suits, to suits involving the testing of drugs and devices and procedures on human subjects, not to mention labor disputes between interns and nurses over job requirements. The counsels of universities with problems like those tend to yawn when I discuss with passion some of the kinds of cases we have.

“The cases of most fundamental concern to us are those that speak directly to the nature of this university. For example, we may feel especially affected by the increasing pressures for ‘publicness’ because we are unusually private for a great research university, surely one of the most private of them. Perhaps we have more to lose from the trend toward adversary relationships between the university and its faculty and student body, because we are traditionally more familial — more of a community — in structure and style. We may feel more strongly the pressure to substitute a regulatory system for consensual arrangements, because we have remained remarkably consensual while many other institutions have already become more regulated in the sense of having rules spelled out and leaving less to individual judgments.

“If you don’t have an Honor Code — and most universities don’t — you aren’t threatened by pressures to make you give it up. If you have retained less of the ancient ideal of a university as a community of scholars and teachers, set ‘apart’ from the world in some measure, nourished by the atmosphere of an academic preserve, you have less to lose from pressures to be more accessible. Though a world-scale research university, Princeton in these respects shares characteristics of much smaller private colleges — but with more visibility and more points of contact with the society.

“At the same time,” he added, “if Princeton feels more threatened in some ways than other universities do, we have exceptional resources — and I don’t mean money alone — for defending ourselves.”

Such as?

“Well, in the first instance, I think we protect ourself by avoiding unnecessary litigation. A well-run institution should not be confronted with a large number of wasteful law suits. Problems should be anticipated and avoided; alternative means of conflict resolution should be available. Some degree of litigation is probably inevitable these days — perhaps even a sign of health in some respects — but in other respects it’s remarkable how few suits have been brought against Princeton.

“One student has gone to court against the Honor Code process, though a dozen or so in the last few years have been penalized after Honor Committee procedures without claiming they were fundamentally unfair; and many more students of course have received disciplinary penalties of varying degrees from other university officers or committees. We are not involved in two faculty complaints, but more than 30 faculty members a year do not receive reappointment or promotion, and don’t sue, even though job prospects in many fields are now very poor.

“When we are confronted with a law suit, however, we have the resources and willingness to respond effectively. The university has acknowledged error and reached amicable settlement in several matters in recent years. But where we believe our position is correct, and that the issues are important, we have been willing and able to defend the institution vigorously.

“Subtle, but important, assets for Princeton in the face of increase litigiousness and government pressure are various special characteristics of this university, including its administrative style. There is a tradition at Princeton of centralized administration under strong and accessible presidents. This permits more effective administration than the decentralized systems that have developed at many other major universities. Princeton, as educational institutions go, is a ‘well-managed store,’ able to defend itself effectively because it follows reasonable procedures, can present facts and reports quickly, and is generally less likely than other to be embarrassed by its own errors when called upon to defend its rights. For example, when government auditors come to Princeton, they find that millions of dollars have been spent essentially without error. That is not true everywhere. It puts this university in a strong position.

“In addition, Princeton alumni are in positions throughout the society to be helpful when called upon to assist the university. And in general they are uncommonly willing to help. Trustees especially —but not they alone— have gone to bat vigorously and effectively when vital interests of Princeton were at stake.”

To judge from Wright’s visibility on campus and the frequency with which he is quoted in the Princetonian, he is pretty accessible himself. “I probably have more contact with students than do my opposite numbers elsewhere — and with less sense that we are potential legal adversaries. Most of the questions students want to talk over with me are at least quasilegal; but a lot are more quasi than legal.” Wright also maintains close ties with faculty, serves on committees with them, has friendships and professional relationships that go beyond the usual lawyer-client one. “And this is extremely helpful.”

And unusual?

“Yes. Even in the Ivy League, while most lawyers are close to their presidents, I believe they are less likely to have a clear sense of what representative members of the faculty or student body think on a given issue. When you go outside the Ivy League the contrast is more extreme. I attended a meeting in Chicago recently with lawyers from a dozen non-Ivy institutions ranging in size from a major public research university to a small private college. As we sat around the table it was distressing how unlistened to they felt.

“At Princeton, I feel directly in communication, feel ‘close to the client,’ as lawyers say. And in most situations it permits me to speak about ‘Princeton’s position’ on an issue, knowing I’m not expressing only ‘what Princeton’s lawyer thinks’ nor not just ‘what the Princeton administration’s positions is’ but ‘what Princeton’s position is.’ This is true because when any significant issue arises, the president will discuss it with the relevant faculty committee, with the executive committee of the University Council, with student leaders, with others who may be knowledgeable or interested, and always with the trustees. I sit in on some of these meetings and am briefed on the others. As a lawyer I can then deal with issues with the confidence that this backing provides.”

When Wright was considering leaving the Ford Foundation — where he had been assistant general counsel for three years after spending three years as an associate with the Washington, D.C., law firm of Covington and Burling — he got strong advice not to take the Princeton job, “because I would be a ‘second-class’ citizen in a university. On the contrary, I have found it and ideal situation for a lawyer. Lawyers frequently complain, ‘If only I could sit in on the making of policy decisions!’ — to help avoid unnecessary litigation. They rarely have that opportunity because lawyers are commonly seen as troublesome people one calls on only when in trouble — to guide one through arcane thickets set up by other lawyers. A gratifying aspect of this job is that I have been allowed to ‘come to the table.’ It’s one of the distinctive things about Princeton. Elsewhere, especially in larger institutions, lawyers are more likely to be pigeon-holed, forced to stick to their knitting.”

Unpigeonholed, Wright sits on the President’s Cabinet along with a dozen top officers including the deans and vice presidents. As secretary of the university, he attends trustee meetings and takes minutes — in longhand — and is secretary of the trustee executive committee and of the committee on committees and serves on many boards related to the university, including Princeton University Press and McCarter Theatre, plus several foundations. Son of a minister — the retired Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of East Carolina — and an active churchman himself, Wright was appointed by President Bowen to chair the search committee for a new Dean of the Chapel which led to the appointment last spring of the Rev. Frederick H. Borsch ’57.

“How a university counsel performs is partly institutional style and partly his own taste and style. Some counsels take a more specifically and insistently legal approach than I do, sternly warning their universities that certain acts and policies ‘will get you in trouble.’ That can work well if the university ‘knows where he’s coming from.’ Such a lawyer gives up something in the decision-making process, but gains in clarity of perspective. Because I am drawn more into university decision-making, there is a danger I may not adequately represent the specifically, narrowly legal perspective. But I try to protect myself and the university by being alert to this risk, and by consulting and employing outside counsel.”

Is he optimistic or pessimistic about Princeton’s ability, in the long run, to preserve its distinctiveness against the new litigiousness?

“Optimistic. We have a strong sense of engagement: that the things we’re defending are important for society and for higher education as a whole as well as for us. Of course Princeton is going to change — must change to stay alive — but I have the good feeling that we will not be carried along with the drift of things. In defining and defending the character of the institution we are helping to shape our environment and at the same time shaping ourselves. It’s not good for a university to develop in isolation any more than to be a passive creature of its times. We have to be active and creative in the tension between the institution and the environment.

“We’re steering out own course in some measure, and yet we’re involved with the powerful forces of our time; and that strikes me as a pretty healthy way to be.” He compared this with the period when Woodrow Wilson was Princeton’s president, calling that “one of the great times of the institution’s history, because Wilson took Princeton into the main currents of national life. The faculty that he brought in, the students, the alumni, the trustees with resources they made available enabled Princeton to raise major educational issues and influence all of American higher education. The right decisions may not always have been made, but Princeton was involved in the great educational issues of the time. And I think we are today.

“The legal issues on which we have taken a stand are important to all of higher education, but they are issues on which other institutions are unlikely to speak out if we don’t, either because they don’t value the principles involved as much as we do, or because, though they value them as much, they are unable to speak with clarity and effectiveness because of political pressures, in both the broad and narrow senses. And in such instances when Princeton successfully defends an element of academic of institutional freedom — which may be particularly important to this institution — our action benefits institutions less sensitive to that particular freedom. For example, by protecting our right to have an Honor Code administered by students, we encourage others to pursue their own ways of doing things in their own contexts, to defend what works best for them, and not assume they must accept every uniform regulation or ruling they’re threatened with. By defending our right to make our choices we are defending the right of others to make theirs.”

This was originally published in the May 18, 1981 issue of PAW.

No responses yet