When Princeton’s Board of Trustees committed to undergraduate education in January 1969, President Robert Goheen ’40 *48 said the admission of women that spring was unlikely, given the challenges of facilities and finances. But by April 20, many of those hurdles had been cleared, allowing Goheen and the trustees to announce “phase one” of Princeton’s coeducation plans, beginning in the fall semester, complete with charts and graphs. PAW covered the news in its May 6, 1969, issue.

Plans For Coeducation: Gift of $4,000,000 Plus Princeton Inn Solves Initial Problems

By Landon Y. Jones ’66

(From PAW’s May 6, 1969, issue)

The reaction was predictable. Hardly had President Goheen and the University’s Board of Trustees completed the most important single announcement in Princeton’s history than WPRB’s jubilant announcers switched from the press conference to play a stirring rendition of the Hallelujah Chorus. Though the Daily Princetonian’s editorial writers have recently found little room for agreement with Nassau Hall, they waxed eloquent the next morning in congratulating the Board on its wisdom and foresight. Only a few scholars, astrologers, and other free souls may have noticed that April 20 is the day Chaucer’s pilgrims arrived at Canterbury. Yet everyone in the University community was ready to appreciate the fact that April 20 is the day coeducation came to Princeton.

At a time when most universities have to contend with rising student-faculty discontent and dwindling financial capabilities, Princeton’s decision to educate young women is unique in that the major difficulties inherent in such a profound change in the University’s direction have already been met. One reason is that the groundwork has been carefully paved. It was nearly two years ago when the University’s Board of Trustees first suggested that a study be prepared on the possibilities of coeducation at Princeton. A year later in July of 1968, Economics Professor Gardner Patterson presented his committee report which concluded that the “quality of the educational experience at Princeton would be greatly enriched if women were admitted” — but at an estimated cost of $25 million. After the faculty overwhelmingly endorsed the recommendations of the Patterson report, the Board of Trustees last January committed Princeton “in principle” to coeducation and asked the administration to present its plans to implement it. The Trustees’ action last month — which will bring 130 female undergraduates to Princeton in the fall, accepted the proposals submitted by a joint facultyadministration-student committee chaired by President Goheen.

Praise From ‘The Prince’

Coeducation has been long proposed, and opposed, at Princeton. The board could have heeded the pleas of reactionary alumni to put off implementation of the January “in principle” acceptance of coeds. Long enough delayed, the trustees finally chose to side with progressive forces in the administration and student body to make coeducation a reality this fall. By approving the plan the board implicitly acknowledged the arguments for coeducation which students have propounded for so long. The decision shows courage and responsiveness to student needs. This precedent will hopefully be followed in future board actions.

That responsiveness is indeed expanded by what could tum out to be the most important of all the decisions made Saturday. The board voted to give present students a formal role in deciding major university policy. Granted, the role is small. But it still marks the vital first step and recognizes the appropriateness of a student role in this decision-making.

The board has been much-maligned in the past and perhaps with good reason. But only the highest praise is appropriate for Saturday’s meeting. The trustees showed courage, foresight and an ability to change with the times that would do credit to any deliberative body in the country.

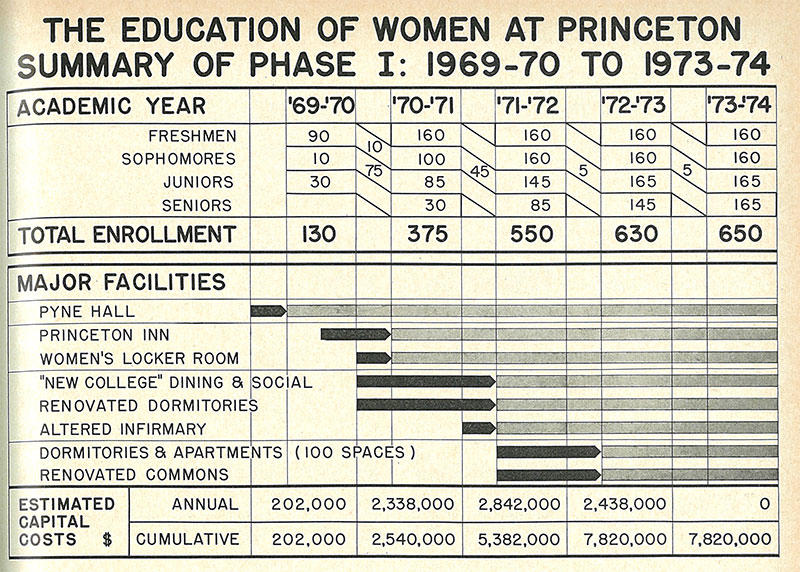

The most dramatic reason for the feasibility of bringing coeducation to Princeton is that many of the considerable financial worries disappeared with the snows of January. Under the University’s detailed, step-by-step immersion plan — not unlike a newlywed mapping his first years of household budgeting — Princeton will slowly build from a base of 130 girls entering next fall to a total of 650 by 1973. The capital costs of the fiveyear “Phase One” plan will total only $7.8 million, far less than the Patterson Report’s estimate of $25 million for 1,000 girls (though an additional $2 million will be necessary to meet increases in student aid). Princeton has already raised what could be called a tiger’s share of necessary funds. In his April 20 announcement, President Goheen revealed that an anonymous donor has contributed $4 million to give coeducation a firm shove forward. “This wonderful pledge provides us with a most handsome start for a most critical and important undertaking,” he said. “It will enable us to take advantage, with delay, of the strong interest in moving ahead with the education of women, which is shared by so many members of the University community.” President Goheen added that he felt confident that the remaining $5.8 million can be raised without extraordinary difficulty.

In terms of long-range planning, the economic virtue of Princeton’s model for coeducation lies in assimilating women completely into the student body instead of building an independent or coordinate women’s college. Princeton will avoid the costs of duplicating existing administrative and academic facilities and will provide a variety of residential and social options. In practice, education at Princeton will most closely resemble that at Stanford, where an established ratio of men to women is maintained, with all students fully integrated into the University community. Women students will be able to choose among living in a women’s dormitory and eating at Commons, at a newly-established hall like Stevenson Hall or Wilson College, or possibly at certain clubs. Otherwise, they could live in a dormitory attached to a sub-college and take meals at the college’s dining facility. In all cases, the University believes that both men and women will benefit significantly from the continued exchange of ideas, attitudes, and perspectives that comes from a shared educational experience cutting across all areas of the college environment.

Still, the increased numbers of students alone will eventually require new living facilities — and in this area the University has hit upon at least one ingenious — and surprising — solution. Long the stronghold of parents and weekend dates, the 45-year-old Princeton Inn has been purchased by the University (which already controls 85 per cent of it) and will be converted into a residential college for 375 students in 1970. Though the acquisition and conversion costs are estimated at $1.5 million, the use of the Inn will represent a significant saving in construction and operation costs. In announcing the purchase, President Goheen said he regretted “having to take the Princeton Inn out of general community use,” but pointed out that local and alumni usage has been steadily declining and that the Inn’s largest single user is the University itself.The bulk of new construction and operating costs will fall in the middle of the five-year “Phase One” plan. Next year, the University will spend only $200,000 in admitting 90 freshmen and 40 transfer female students and will be able to house them all in Pyne Hall. Over the following four years, Princeton will admit more transfer students and 160 freshmen women each year — at a total cost of some $7.8 million, which will be met by the $4 million gift and further financing. Though Princeton’s physical expansion in recent years makes no additional classroom or lecture space necessary, the University will have to construct new facilities in Dillon Gym and begin refurbishing such antiquated structures as Brown and Witherspoon Halls. Further, the addition of a distaff constituency in the University will require the hiring of more female professors and administrators. The Dean’s Office has already begun interviewing candidates for the post of women’s dean.

By 1972, the growing numbers of female students will expand beyond the capabilities of existing dormitories, requiring the addition of a 400-student “third” college, a combined dining and residential complex that will likely be built near Pyne Hall or the New New Quad. It is expected that Commons will be renovated; Holder converted into a residential college, and another new dormitory-apartment complex will be built, probably behind McCarter Theatre. After the five-year period, Princeton will continue to accept more female students “as promptly as possible” as the financing becomes available until a total of 1,000 women undergraduates forms the desired 3:1 ratio with male students. “Many young women today do not want to be kept out of competition with men in University life,” said the report of President Goheen’s ad hoc committee, “They believe that by participating fully with men while at college they best prepare themselves for the adult world into which they will be moving — a world in which women are finding more and more opportunities to participate equally with men.”

In fact, one realization that has lately begun to unsettle a number of young Princeton men is that the new breed of Princetonians may be only too qualified and give an unlady-like blow to the rock of male supremacy. “The boys are in for a shock,” one admission worker recently commented, while thumbing through a sheaf of female applications. “Some of these girls are going to knock them on their ears.” Even before the Admission Office began to accept applications in January, hundreds of pioneering girls had inquired over the fall and winter about entrance to Princeton. Not surprisingly, some of the hopeful lasses were either student girlfriends or women simply receptive to the idea of a masculine ambiance. Yet most were academically superior candidates who wanted to receive a Princeton education. In selecting women for the Class of ’73, Admission Director John T. Osander ’57 found that they were individually as strong — or even stronger — candidates than their male counterparts. “We feel that the quality of accepted women is exceptionally high,” he said. “The 130 accepted, and the 116 additional girls placed on the waiting list, are students whom any college in the country would be proud to accept.”

Initially, the Admission Office was worried that it might not find the time to take any women at all. In addition to choosing the male class, Mr. Osander and his staff of 10 admission officers — all male — had to devise ways of judging female applicants — no mean task — and decide if the girls could form a quality class. Their first step was to bring in a feminine viewpoint in the form of Mrs. Carol Thompson, a young faculty wife who had earlier worked in the admission office at Radcliffe College. Once applications from the girls began to flow in — but still with the understanding that Princeton might not choose coeducation — Mrs. Thompson and two part-time female helpers began to sort through the applications and make their first evaluations.

Though men and women cannot always be measured on the same yardstick — some girls sent in poetry and drawings instead of writing samples and talked on modern dance instead of football — the admission women tried to use the same objective criteria employed in selecting males. The only problem was something called feminine intuition. “All of the girls were exceptionally bright and talented young women,” explains Mrs. Thompson. “But we tried to avoid the superficial types by finding the ones who not only had interests, but had the will to do something about their interests.” At times, the advice of the women contributed both heat and light to the admission procedure. “They did a remarkably sound job for people not experienced in admission,” says Mr. Osander. “But sometimes we had some dandy arguments. All the men would look at a girl’s academic record and her SAT’s and decide not to take her. Then Carol would say that she ‘felt’ something promising about the girl on the basis of her writing sample. She and the other girls put a lot of emphasis on qualities of heart in addition to sheer intelligence. Sometimes they won the fight, sometimes we did.”

The profile of the group of women accepted this year does not necessarily reflect that of future Princeton classes. Mr. Osander explained that the majority of female applications this year were self-selective: that is, drawn in the absence of normal University recruiting activities. Without a clear Trustees’ decision on coeducation, the admission officers did not canvass for secondary school women, office interviews with girls were not conducted, and Princeton alumni schools committeemen — some 1,500 voluntary workers in every state — were not instructed to search for eligible young women. “We have far less diversification in the female applicants than in the male applicants,” Mr. Osander said. “Most of the girls are from what are considered ‘good’ schools; most are from the East; most are at least well-to-do. We had many excellent applications from 52 alumni daughters (22 were accepted), an unusually high percentage of the total. It was apparent that many of the girls were applying because of their particular circumstances: either they were bright young women who heard of Princeton through their school, or they were alumni daughters kept informed by their fathers’ strong interests, or both.” Mr. Osander also points out that, as expected, the women applicants have a strong bent toward such disciplines as art, music, and languages. There are few future Princeton female engineers.

“At first, we were concerned with the lack of diversity,” Mr. Osander acknowledges. “But after we satisfied ourselves that Carol’s ratings were accurate and that the girls were obviously so well qualified, we decided to go ahead and accept them on their merits alone, not worrying about demographics.” The only exceptions were made in the cases of black and disadvantaged applications. Aware that such girls would not be expected to know of Princeton’s interests in coeducation through normal hearsay, one admission officer, Spencer J. Reynolds ’61, embarked on a recruiting campaign and succeeded in drawing applications from 23 black and disadvantaged women, ten of whom were finally accepted.

In addition to the 90 freshmen girls, the University hopes to admit 40 female transfer students — sophomores and juniors — next year (thus placing the first female Princeton graduates in the Class of ’71). One surprising development was that the female transfer students were generally not as intellectually exciting as the secondary school seniors who applied. “The problem is that there are lots of girls who are either restless, unhappy, or just whimsical,” said one admission worker. “For a while, for instance, we were saying that it looked as if a whole class at Wellesley had applied.”

A healthy number of the admitted women have indicated that they hope to go on to graduate school. One fourth are prospective science majors. But because no interviews were conducted, the real nature of Princeton’s girls is still a question. “It’s hard to say what they’ll really be like” says a faculty wife who worked on selections. “They’re terribly bright and terribly mature. They will be scrutinized and will be on constant display. They’re going to have to be able to handle themselves.” There seems little doubt that the new Princetonians will be able to do just that. One teacher wrote in her recommendation that “this girl is the absolute best we have to offer.” Another girl was described as “the sort of girl I wish I had as a daughter.” Not the least welcome of the young ladies, however, will no doubt be the one described thus: “She could be a pulchritudinous addition to Princeton’s student body.”

1 Response

J.E. Murdock III ’69

6 Years AgoBreaking the Story (A Special Talent)

Bob Durkee '69 broke the story by interviewing President Goheen and asking enough questions to allow the reporter to read the report on the president's desk. The special talent was that Durkee was fluent in upside-down reading. The irony is that Bob has held one of the most trustworthy jobs since. Maybe upon his retirement, Bob will reveal other stories!