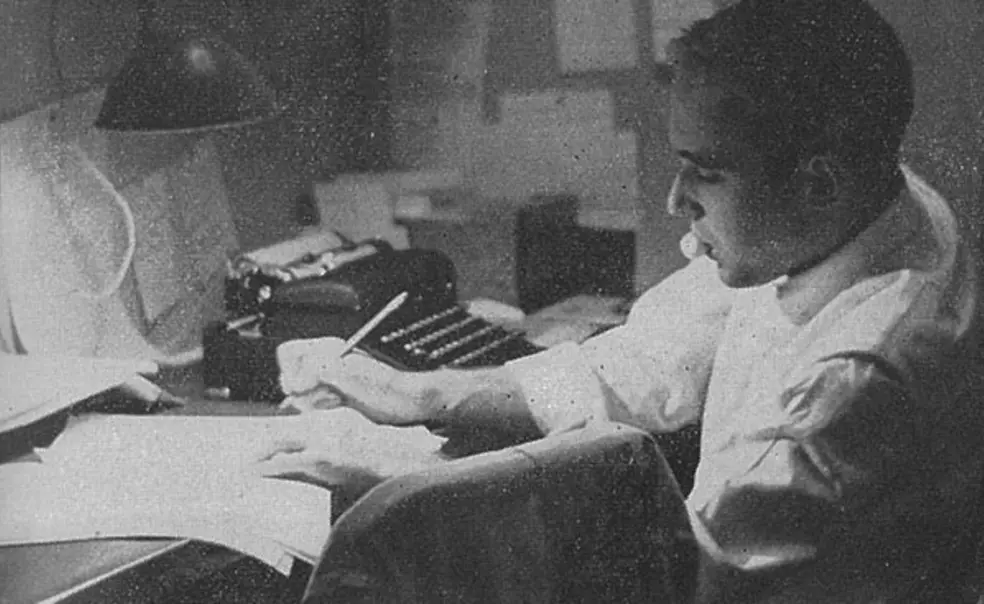

Richard Kluger ’56 certainly knows how to write. He’s published 13 books, including Ashes to Ashes, an 800-page study of the cigarette business and American public health that earned him a Pulitzer Prize. Nevertheless, he put off writing his thesis. On March 9, 1956, PAW published “The Thesis Blues,” a short satirical essay that Kluger wrote in his senior spring.

“Anyone with a box of typing paper and a book or two at his disposal can write a thesis,” Kluger writes in the piece. “The trick is to give the impression of a feverish, utterly devoted academic activity probing into realms never before trammeled by white bucks while, at the same time, maintaining a well-rounded schedule for goodfellowship and gaiety.”

The essay pokes fun at classmates who pick esoteric research topics and overstuff their bookshelves to curate this image of academic devotion. Armed with toothbrushes, coffeemakers, and electric fans, they descend upon the library basement to “take up permanent occupancy” in their carrels each fall. They stay on campus for academic breaks, though their resolve to write quickly fades.

The author bio on the piece said Kluger “hopes to graduate in June — if he can get to work on his thesis.” Self-deprecation aside, he did finish and graduate on time. Kluger did not choose an obscure, self-important topic like the English major in his essay who wrote on “Imagery in Albert Payson Terhune.” His title was almost quotidian in comparison: “Ego in Arcadia: A Study of the Romanticism of Thomas Wolfe.”

The Thesis Blues

To avoid working on his thesis a senior writes an essay on how to avoid working on his thesis

By Richard Kluger ’56

This is the season of the senior thesis, and it has come to our attention that a considerable body of material has been devoted to other undergraduate problems—those harrowing first months of transition from well-scrubbed boyhood to graceful knowing manhood, the gleaming dentures and glib tongue required in the accursed Bicker, the lack of sufficient extracurricular “wheelspace” in which gifted Princetonians can strut their talent, and all the rest—but nary a word about the senior’s summa theologica.

Now anyone with a box of typing paper and a book or two at his disposal can write a thesis. Our concern here, therefore, is principally with the code of ethics and behavior surrounding the production of the thesis. At all times, in the procedures suggested below, the trick is to give the impression of feverish, utterly devoted academic activity probing into realms never before trammeled by white bucks while, at the same time, maintaining a well-rounded schedule for goodfellowship and gaiety.

The first item on the agenda is perhaps the least important, and that is the topic one chooses. Anything is possible thesis material, but, generally speaking, the more esoteric your topic, the better. Besides, anything that sounds interesting has been written about five times in the last year and there are three other guys in your department writing on the same thing. So obscurity is the trend in present day thesisoneupsmanship. An English major, for instance, scores heavily by writing on, let us say, “Costumes in Pre-Elizabethan Drama” or “Imagery in Albert Payson Terhune,” while a budding historian might do well to consider “Problems in Ethiopian Diplomacy, 1937-39,” always keeping the focus sharp and narrow.

Having determined to be pedantic, you are already one step ahead of the game. Your classmates are duly impressed with your desire to pioneer through the frontiers of wisdom and become distressed at the commonplace nature of their own masterpieces.

Second, it is important to be seen leaving campus at the end of junior year heavyladen with volumes pertinent to your topic. Again, the actual amount of reading completed over the summer months is all but irrelevant; it is just the being seen that counts.

Upon returning to campus (with the books, preferably but not necessarily) the senior drinks in the tangy flavor of autumn, bounds briefly over the crunchy lemonyellow and blood-red leaves that blanket the earth, and then slips into the nearest phone booth to line up a typist for his thesis, eight months hence. By disclosing shortly thereafter that your typist has already been contracted, you again score with the distinct implication you’re either about to start writing or, in fact, have already completed your 20,000 word quota and are applying to your departmental chairman to have the limit doubled—things developed beyond your wildest dreams, you explain. Other seniors, without a typist but with their base reading completed and their outline drafted, feel they are behind in the game, set about to line up a typist of their own and are thus deftly distracted from the real business at hand.

Next, the senior checks in at the library and discovers he has been awarded a carrel. Elated at having a cubicle of his own after lo these many years, he then (a) cannot find it (b) cannot open it—those darn combination locks are absolutely impossible (c) having punched his fist through frosty glass panel to gain admittance, learns that he (d) hates his carrel-mate or that his carrel-mate is also his (e) roommate and that neither of them is allowed to (f) smoke in the carrel.

But now you are ready to get down to business. You install yourself firmly in your carrel, bring along a coffee-maker and a toothbrush, hang tip a huge calendar with little jottings of duties to be done each and every day of the month (e.g., “Check Britannica re item #7,” “buy new eraser at U-Store,” “get haircut”) and plug in your electric fan, providing you are in the Fanners’ School.

The problem of the electric fan is not an inconsitlerable one, and seniors, according to the latest straw poll, are roughly divided in their sentiments on the matter. The crux of the matter is, does the feeble zephyr activated by the spinning blades warrant the annoying hum the machine produces? And if you think it does, how about your carrelmate? And if he can stand the racket, how about the people across the aisle from you?

Thus installed, the oneup senior starts laying in a supply of books. Perhaps the suavest of all ploys is to prowl about the C Floor in search of a loose shelf which, when found, is added to your own carrel. Then, with several million books in the vicinity, you merely choke your three shelves with the thickest volumes available, with one or two of them written in German or French—you lose so much in the translation. Bulfinch’s classical dictionary is a must, no matter what your department. And, furthermore, it is important to arrange your books so that you present a liberal interspersing of yellow cards (meaning the book can be taken from the library) with the more banal green cards (meaning they must stay inside the building) that stick out of the inside cover.

With your array of books in place, you take up permanent occupancy, inform the authorities that your mail is to be delivered to the carrel, and await your first visitor. In good humor, the visitor pokes his head through the door, gasps at your bookshelves and, calming himself lest he betray the effect you have obviously made, asks how things are going. “Well,” you sigh, “not bad, but there is so much research to do on this business I can’t see how I’ll possibly be able to start writing before November 15.” Since the fellow intended to start writing his shortly after nfarch 1, he stifles a little yelp and retreats, thoroughly submarined by your superior tactics.

It occurs to you then that perhaps you might begin poking around and do a little reading on your subject. But before one starts to read, one must be prepared to take notes on that reading. And of course, one would not think of using a loose-leaf notebook to take notes in for a thesis. Nobody seems to know why but that’s the way it is. Note-cards and only note-cards are acceptable for thesis action.

Again a debate occurs. Does one purchase big cards or little cards? The Little Card People are adamant: little cards are handier, and they’re easier to cross-file, and if you want to write down just a single quotation per card, it’s easily done without wasting all the space that the bigger cards present. The Big Card People are equally outspoken: you don’t have to switch cards so often, and you can get more on a card, and rather than stressing the conciseness of statement the Little Card People propose, it’s preferable to mark down extended and elaborate quotes which can be distilled and trimmed when the time of actual thesis composition arrives.

Having decided on large or small cards, the next problem is how to index same. Efficiency is vaguely sought; the important thing is to insist that your method is best, despite the fact that you and everybody else know nothing whatsoever about how to set up a file.

When one starts reading and note-taking—as sooner or later one must in this little game—one discovers he is absolutely nonfunctioning without a smoke, which to be sure is taboo. That is, it’s taboo if they find out, they being those people somewhere upstairs and inside offices and far away generally, so what does a little drag mean anyway?

And though cigarettes are pretty much standard fare, a distinct upsurge is to be recorded among cigar- and cigarillo-smokers. Much will depend upon what department one is in and the nature of his reading matter, of course; English majors are heavily infiltrating the cigarillo camp, thanks to the effective advertising campaign of the Robert Burns people. The sociology boys, for example, are almost universally true to thick pipes (the horn rims are optional).

But the problem arises: Where does one dump the ashes? The library officials inspect every inch of terrain carefully the next morning.

Careful attention to kindergarten techniques now pays off, and here’s where the Big Card People are made. The play is to take a large filing card and fold it—as one learned to do in the days of bygone youth—so that a sandbox-like structure is formed. Little tabs are then chopped out of the side of the makeshift ashtray, the size of the tabs depending on whether one smokes cigarettes illegally, cigarillos illegally or cigars illegally.

At the evening’s end, one carefully places the paper ashtray in his index box, patters across the floor in stocking feet, slips furtively into a seminar room nearby and dumps his contraband into a strictly legal ashtray.

Most heroic of all thesis ploys is the Christmas martyr. While underclassmen, in their gay mad frantic desire to scram, stream out of town in mid-December, the tactful senior brings in a supply of groceries, a dozen erasers from the U-Store and a portable radio. The library was actually bulging (well, not bulging exactly) with seniors who foresook (foresooked?) Mom’s dumplings for their thesis. “Can’t get a thing done with all those kids around” is the standard line, when, of course, it is only other seniors who interrupt other seniors’ investigations every twenty or so minutes.

One group we know of, tiring of their martyrdom after two days of the vacation break, scurried over to Woolworth’s and returned with a fleet of wind-up toy racing cars. The initial enthusiasm with which the sport was greeted was overwhelming. Races were conducted on the half-hour, strictly for the sport of it; for gambling is ungentlemanly. Soon, two tracks were being operated simultaneously: the hard concrete track on C Floor was preferable for certain models, while others felt the slick, inlaid linoleum surface on B Floor was a finer track. Not long thereafter, obstacle courses were planned, by opening a book in the middle and placing it facedown on the floor. Races have been known to be run, even, over Milton’s “Areopagitica.”

When the races failed to amuse, the martyrs headed home.

While the techniques herein suggested seem perhaps intellectually unstimulating, they do serve to advance one in the sphere of -the social graces and savoir-fairemanship—that is, until one leaves his carrel and looks next door where the fellow has four bookshelves plus a pile of Manchester Guardians, a watercooler, a hi-fi set, a burnished oak index file and a calendar with his urgent duties scribbled in Latin.

Alas! You have been outgambitted.

No responses yet