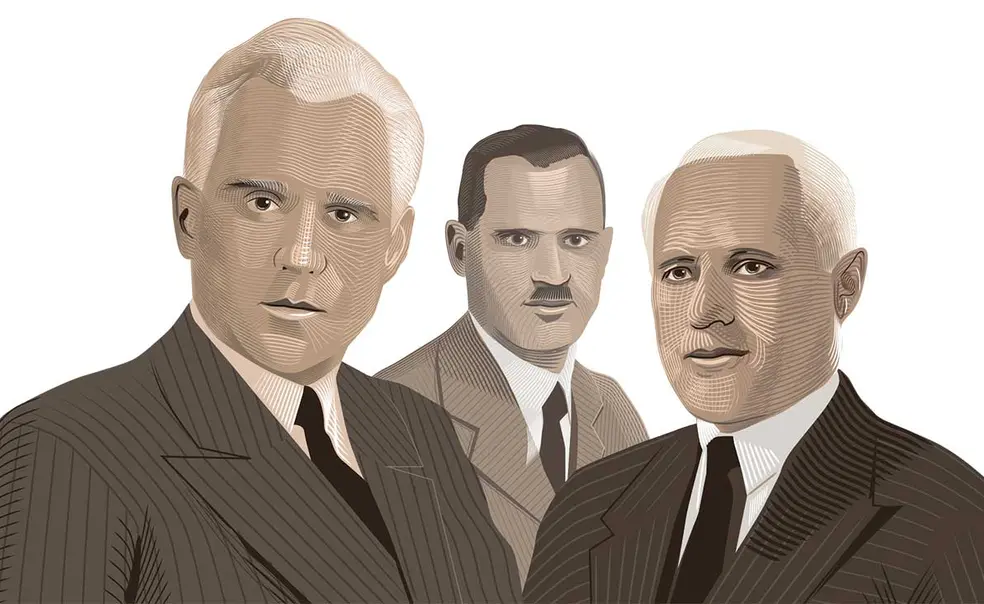

Three Brothers Who Became University Presidents

Princeton Portrait: Karl Compton *1912 h’34, Wilson Compton *1915, and Arthur Compton *1916

Princeton produces, proportionally, a suspiciously high number of university presidents. Presumably Princetonians see how the job should be done and then decide to go forth and tell the world. In one celebrated instance, three brothers who all attended graduate school here — Karl, Wilson, and Arthur Compton — went on to become leaders of three different universities. Before they donned their Tudor caps and four-chevron gowns, their adventures in their respective fields took them into some of the most dramatic intellectual theaters of the 20th century.

Karl took a Ph.D. in physics in 1912; Wilson, a Ph.D. in economics in 1915; Arthur, a Ph.D. in physics in 1916. In those years, the fields they worked in were still emerging as mature disciplines. Karl and Arthur wrote their dissertations on atomic physics, which turned out to be a prescient topic, especially since two of the three basic components of an atom — protons and neutrons — hadn’t yet been discovered when they graduated. For his part, Wilson studied in the Department of Economics. When Karl began his studies, the Graduate College wasn’t yet built; when Arthur finished his, the building was complete, a solemn crown of gray spires that has defined West Campus ever since.

Soon after graduating, Karl joined the faculty of the University’s Department of Physics, where he gained a reputation as one of America’s leading experts on the atom. (He was also an early prophet of the modern research university. In 1928, he told the Princetonian that good researchers are as important to a university’s faculty as good teachers — a bold claim to make in the United States at the time.) In 1930, he became president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He led the institute through the war years, a period of low resources and high stakes when many scientists worked in buildings hastily constructed from plywood. The work that came out of those plywood palaces — including the invention of radar — was so impressive that the era of Compton’s presidency, especially the bricolage architecture and philosophy of move-fast-and-break-things, remains at the core of the institute’s self-image today.

Karl was also an early prophet of the modern research university. In 1928, he told the Princetonian that good researchers are as important to a university’s faculty as good teachers — a bold claim to make in the United States at the time.

Wilson taught economics at Dartmouth and then, in 1945, became the president of the State College of Washington — now, Washington State University. His tenure stressed the importance of public colleges for driving state economies and readying students as civic leaders; in education, he said, “cultivation of the spirit of service is of first importance.” Princetonians will recognize the philosophy.

Arthur became a physics professor at Washington University in St. Louis, then the University of Chicago. In 1927, he won the Nobel Prize in physics for his work on X-rays. During the war, he headed the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, part of the Manhattan Project. There, he coordinated the work of an unlikely alliance of specialists, tried to keep them from blowing up Chicago, and guarded the lab’s secrets — the first being that the name was a cover; there was no metallurgy at the Metallurgical Laboratory.

In 1946, he became the chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis, which wanted him to help build up the engineering school. He set himself a bigger task: “While I was sympathetic with developing the engineering school, the great need that I saw was for first-class liberal education, where young men and women could learn to guide wisely the powers of the nation. I was particularly concerned with seeing that the students should learn to know what freedom means and be willing to assume the responsibilities that go with freedom.”

Each of these men made remarkable discoveries and helped to shape famous institutions of knowledge. But when they returned to Princeton to give talks, accept awards, or otherwise be covered in honors, the campus papers would describe them in terms of their greatest local fame: “one of the Compton brothers.”

No responses yet