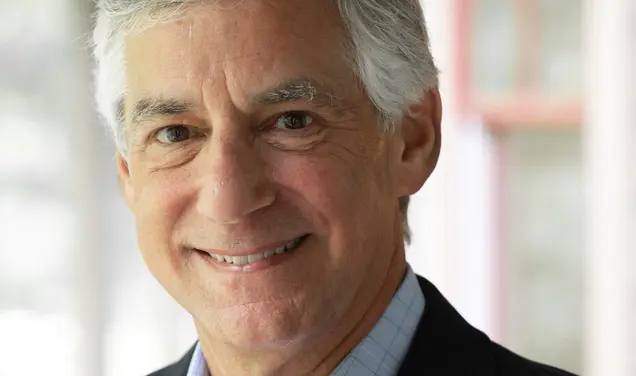

Through Poetry, Joshua Bennett *16 Speaks ‘to the Human Soul’

‘I was always trying to express the music in my head with the people I trusted’

Joshua Bennett *16 remembers his first experience of poetry as listening to ministers preaching their sermons on Sunday morning. He found that the poetry of the sermons wasn’t just defined by the use of symbolism or metaphor, but by how the words affected the listeners.

“Seeing that as a young boy taught me something I haven’t forgotten since about the power of language, especially language that’s memorized and that’s used in the service of something higher than oneself,” he says.

Bennett is now an award-winning poet and professor of English at Dartmouth, but he got his start improvising sermons for his family after church, practicing the gesticulations and intonations of the ministers he had just heard. The poetry he began writing as a 4-year-old still sits in a shoebox at his mother’s house, as does the trophy from his first poetry slam at the Yonkers Public Library as a tween.

“It was always just my way of expressing myself, whether I wrote it on the page or tried to pull language from the air,” he says. “I was always trying to express the music in my head with the people I trusted.”

He started really competing in regional and national poetry slams as a senior in high school, around the same time he read Race Matters, by Cornel West *80, and decided he wanted to become a professor. Though he planned to be an Africana studies major at the University of Pennsylvania, he switched departments during his junior year when he realized he already had close to enough English credits.

After Bennett performed at the White House in 2009, one of his friends convinced him to take his show on the road and get paid for his poetry. He started a spoken word collective with his sister and a group of friends, and they toured across the country and then around the world.

Bennett’s first poetry collection, The Sobbing School, was published by Penguin Press in 2016 as a 2015 National Poetry Series selection, and it was a finalist for an NAACP Image Award in 2017. The majority of the poems were written following the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 and the ensuing protests. “That’s really the center of that book: Black grief, Black mourning, but also Black persistence and meditative tenacity in the wake of state-sanctioned violence,” Bennett says.

His work has continued in the years since that debut. In 2020, he published his second book of poetry, Owed, and his first book of literary criticism, Being Property Once Myself: Blackness and the End of Man, and he also won a Guggenheim fellowship and a Whiting Award. His third collection of poetry and his second book are forthcoming.

“I’m trying to speak to the human soul,” Bennett says, adding that his poetry is meant for a wide audience. “Over the course of my career, I’ve performed in prisons, I’ve performed for politicians. I’ve performed and shared my work with everyone from kindergartners to senior citizens. That’s been the great joy in my life: writing work that is quite specific, but in its specificity, it’s hopefully also universal.”

By Joshua Bennett

with a line from Gwendolyn Brooks

Months into the plague now,

I am disallowed

entry even into the waiting

room with Mom, escorted outside

instead by men armed

with guns & bottles

of hand sanitizer, their entire

countenance its own American

metaphor. So the first time

I see you in full force,

I am pacing maniacally

up & down the block outside,

Facetiming the radiologist

& your mother too,

her arm angled like a cellist’s

to help me see.

We are dazzled by the sight

of each bone in your feet,

the pulsing black archipelago

of your heart, your fists in front

of your face like mine when I

was only just born, ten times as big

as you are now. Your great-grandmother

calls me Tyson the moment she sees

this pose. Prefigures a boy

built for conflict, her barbarous

and metal little man. She leaves

the world only months after we learn

you are entering into it. And her mind

the year before that. In the dementia’s final

days, she envisions herself as a girl

of seventeen, running through fields

of strawberries, unfettered as a king

-fisher. I watch your stance and imagine

her laughter echoing back across the ages,

you, her youngest descendant born into

freedom, our littlest burden-lifter, world

-beater, avant-garde percussionist

swinging darkness into song.

Copyright © 2020 by Joshua Bennett. Originally published in Poem-a-Day on June 24, 2020, by the Academy of American Poets.

No responses yet