Tigers and Dinosaurs

In the golden age of paleontology, Princetonians joined in the ‘Bone Wars’ to build a renowned collection — even if that sometimes meant academic hanky-panky

It’s been 20 years since Jurassic Park dazzled movie audiences with its lifelike, and sometimes terrifying, portrayal of dinosaurs. The film became the 13th-highest-grossing of all time, earning $1 billion at the box office and launching a craze for all things Mesozoic.

Princeton men played a role in popularizing these creatures in the first place. Starting in 1874, a geological museum in Nassau Hall housed a mounted dinosaur skeleton — only the second ever displayed in the world. Campus scientists took sides in the infamous “Bone Wars,” a kind of gold rush to find vertebrate fossils in the American West. And alumni were among the first museum professionals to hire artists to depict extinct animals living in their authentic habitats. A hundred years before Jurassic Park, these efforts helped make prehistoric creatures very famous.

Central figures in this golden age of paleontology after the Civil War were two best friends from the Class of 1877, William Berryman Scott and Henry Fairfield Osborn. As undergraduates they got the idea to launch a series of bone-collecting expeditions to the Rocky Mountains. Both men later became Princeton professors — Scott for a lifetime, Osborn until he was lured away in 1891 by the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where he amassed the largest collection of dinosaur fossils anywhere.

Few people did more than Osborn to popularize dinosaurs. It was he who first announced Tyrannosaurus rex and Velociraptor (shown as especially ruthless killers in Jurassic Park). And he put numerous dinosaur skeletons on public display, including an unforgettable 1907 tableau of Allosaurus dining on Brontosaurus. “In making the American Museum the great center of paleontology in the United States, he created whole dinosaur halls,” says University of Pennsylvania paleontologist Barbara Smith Grandstaff *73. “Other museums copied the way he showed dinosaurs.”

Osborn and Scott collaborated throughout their careers, a friendship that left a lasting monument in Princeton’s ambitious biology-geology building of 1909, Guyot Hall, which they helped to create. To educate the public, its entire first floor comprised a museum; outside were sculpted gargoyles of extinct creatures that Scott and Osborn had helped reveal to the world.

Scott and Osborn came of age at President James McCosh’s Princeton. Deeply pious, the Scottish president — a scientist — encouraged the study of paleontology as a way to understand God’s design of life on Earth, trying to mesh Genesis with Darwin. McCosh believed that life had evolved but was sure the Deity was directing things. In conservative Princeton, his position was considered quite daring; across town at Princeton Theological Seminary, formidable Professor Charles Hodge (“the Presbyterian Pope”) wrote a book in 1874 called What Is Darwinism? (answer: atheistic nonsense, as the orderly cosmos proves). “At this time, I was an ardent anti-evolutionist,” Scott later recalled. No wonder: He lived with Hodge, his grandfather. But views gradually were shifting, and Scott eventually adopted McCosh’s position.

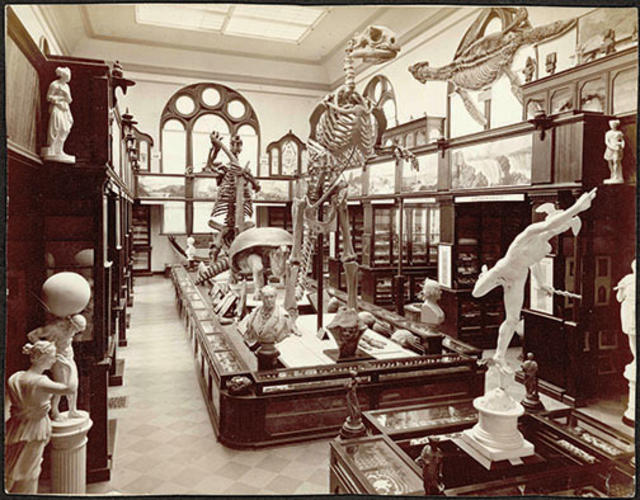

With funding from a trustee, McCosh established a geological museum in Nassau Hall. (It occupied today’s Faculty Room; later its contents moved to Guyot Hall.) Wrapping around the mezzanine were 17 colorful murals that showed prehistoric life and depicted the phases in the geological history of the planet. The artist was an Englishman, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, whose life-size dinosaur models had caused a sensation at the Crystal Palace in London in the 1850s. “His paintings showed ancient life in a vital, dynamic context,” says Robert McCracken Peck ’74, senior fellow of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia and a biographer of Hawkins. “They were continuously on display in Nassau Hall for 30 years — and then for 90 more in Guyot.” Their prominence, Peck says, “gave them enormous power to convince people of the reality of deep time.”

At the heart of the Nassau Hall museum was a plaster copy of the skeleton of a duck-billed dinosaur, Hadrosaurus foulkii, which Hawkins laboriously fabricated. Previously he had assembled the original Hadrosaurus skeleton of bone at the Academy of Natural Sciences, making it the world’s first articulated dinosaur and electrifying the public. Princeton’s replica Hadrosaurus boasted even fewer authentic bits than Mark Twain’s description of a museum dinosaur as “nine bones and 500 barrels of plaster of Paris.” It no longer survives, having accidentally been broken into fragments during the move to Guyot in 1909.

One of Hawkins’ paintings in Nassau Hall, Cretaceous Life of New Jersey, showed Hadrosaurus being attacked by a fierce-looking carnivore called Dryptosaurus. When found 45 miles south of Princeton in 1866, Dryptosaurus was only the second near-complete dinosaur skeleton in the world, after Hadrosaurus, dug up not far away in 1858. “For about 20 years, all American dinosaurs came from New Jersey,” says David Parris *70, curator of natural history at the New Jersey State Museum. “It was the center of just about everything.”

In fact, the Bone Wars began there, three years after Appomattox. Two rival paleontologists — Edward D. Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences (discoverer of Dryptosaurus) and O.C. Marsh of Yale — engaged in bribery and other questionable practices to scoop up the best Cretaceous skeletal remains in the state. The Princeton scientists felt a close affinity with the Philadelphian Cope, a Quaker who sympathized with their theological spin on evolution. “Osborn and I became warm friends of Cope’s,” Scott recalled years later, “and wholeheartedly espoused his cause in the unending quarrel.” As for Marsh: “I came nearer to hating him than any other human being that I have known.”

When Scott and Osborn went west with Princeton’s College Scientific Expedition in 1877, they found themselves at center stage in the worsening Bone Wars, camping in the desolate Bridger Badlands in Wyoming near the Uinta Mountains. Here Cope and Marsh had been scrambling to find prize specimens of Uintatherium, a rhinoceros-like beast with six knobby horns and knifelike tusks. Then as now, nobody was certain what family these freakish creatures belonged to, nor why they suddenly died out some 37 million years ago.

In the badlands, Bone Wars shenanigans abounded: It was Scott, as a fledgling professional, who first realized that an extinct creature described by Cope in a scientific publication was in fact a mix of skull and teeth from unrelated animals, deliberately sprinkled by Marsh’s men in a place Cope would be sure to find them.

The 1877 College Scientific Expedition formed one of the most romantic episodes in the history of the University. Sixteen juniors and new graduates, led by two professors, spent the summer exploring the West for plant and mineralogical specimens, fossils included, to bring to the Nassau Hall museum. Among other milestones, the party was the first to dig in what today is the Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument in Colorado, and it made spectacular discoveries, including 180 previously unknown species of plants and insects — all preserved in crumbly shale.

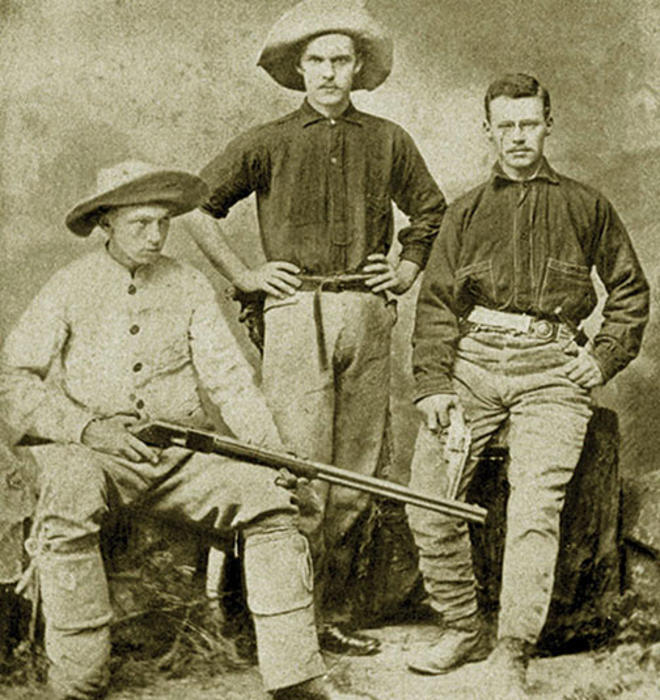

Breaking off from the main group July 21, Scott, Osborn, and three others ventured into the trackless badlands of the Uinta country with Professor Joseph Karge, a feisty former Union officer who had equipped them with firearms from the New Jersey State Arsenal and fully expected Indians to attack — Custer’s men had been annihilated at Little Big Horn the previous summer. Scott’s memoir is a vivid account of a vast, unspoiled wilderness filled with sun-baked gullies and outcrops where, at any moment, one might find a forelimb, teeth, or a skull, each a thrilling “link” in the great chain of evolution so recently proposed by Darwin.

The acclaimed discovery that season in the badlands was the skull of a Uintatherium by Scott’s and Osborn’s friend Frank Speir 1877. Although he was training to become a lawyer, not a scientist, Speir proved the best fossil finder of all — he dug up another skull the next year, too. In his honor, Scott and Osborn named a new mammal species (related to Uintatherium) speirianus.

So successful was the 1877 expedition, Princetonians would return to the Uinta region in 1878, 1885, and 1886 — among nine Western trips the University sponsored before 1895. In this way, Princeton amassed the core of its Vertebrate Paleontology Collection, which by the late 20th century would have 24,000 cataloged items, making it the nation’s finest.

On the 1885 expedition, a drunken mail-coach driver stumbled upon an especially fine Uintatherium skull, complete with a tusk. Among other findings in the rugged badlands were fragments of a creature ancestral to Uintatherium, which Speir noticed during his lunch break one day. The night before, sitting around the campfire, Scott had described what such an ancestor probably would look like, should it ever be discovered, and his prediction proved exactly correct. “Scott was very good as a paleontologist,” says Grandstaff. “He understood the biology of the animals.”

Another important Princeton discovery in the Bridger Badlands was bones from the three-toed horse Orohippus. In later decades, Osborn would popularize the evolution of the horse as one of the most vivid demonstrations of Darwinism at work — partly as a fund-raising gambit for his New York museum, hoping to attract the interest of the horsey set in Westchester County. Many of us grew up reading textbooks that showed Osborn’s classic diagram of steadily larger horses prancing forward across the millennia.

As they each gained professional fame, Scott and Osborn were drawn ever deeper into the Bone Wars, helping Cope in his perennial campaign to undermine Marsh. Under cover of attending the football game against Yale, Scott interviewed Marsh’s disgruntled laboratory assistants in New Haven, who claimed the professor gave them no credit in his published reports. Scott was quoted vilifying Marsh in an exposé against the Yalie in The New York Herald, and thereafter the two men never spoke again.

Meanwhile Osborn brazenly invaded Marsh’s fossil-collecting grounds in the West and tried to discredit him. No less pugnacious than his mentor Cope, Osborn was clear about his goal: to “break down Marsh’s work as far as possible.”

In the ultimate coup, after Marsh died in 1899, Osborn managed to take over the research materials that the professor long had safeguarded in New Haven. He published Marsh’s work on fossil horses and on Uintatherium and related groups in extravagantly oversized volumes — all under the name of Osborn.

Among Osborn’s greatest accomplishments was showing the public exactly what dinosaurs looked like. In this he surely was shaped by his undergraduate days in the Nassau Hall museum, where Hawkins painted and sculpted his dinosaurs and taught courses as a lecturer. To further popularize extinct life, Osborn wrote articles in mass-circulation magazines and hired an illustrator to help him, Charles R. Knight. For an 1896 article in Century Magazine, Osborn sent Knight to Philadelphia to interview the dying Cope. One result of this meeting was Knight’s painting of two of those New Jersey Dryptosaurus dinosaurs scrappily fighting, an image that has become famous in recent years for its affinity to the hot-blooded ethos of Jurassic Park.

Knight went on to become the world’s foremost illustrator of extinct animals. Thanks to Osborn’s involvement, the Guyot Hall museum featured no fewer than 27 Knight paintings of prehistoric life. Today, the surviving — and valuable — murals by both Knight and Hawkins are in storage at the Princeton University Art Museum.

Under Osborn’s often-imperious rule, the American Museum of Natural History flourished, thanks in part to a board of trustees whose names read like a Who’s Who of Gilded Age Tiger alumni. Its fossil collections swelled, eventually incorporating Cope’s many specimens. Osborn stressed showmanship, making sure to send a movie camera along with the colorful expeditions he dispatched to the Gobi Desert in the 1920s, where dinosaur eggs first were discovered.

In his later years, Osborn became controversial for espousing a view of evolution in which “progress” was ordained by some mysterious internal plasm within each organism, an idea that perhaps can be ultimately traced to McCosh’s Princeton of the 1870s, where natural selection was not messily random but rather guided. He also thought some human races had progressed further than others, and in the face of mass immigration he argued for Nordic superiority with increasing vehemence up to his death in 1935. While most of his scientific views have been discredited, he still is regarded as one of the great museum-builders in American history.

At Princeton, few traces remain of the golden age of fossil-hunting. After 91 years of educating the public, the Guyot Hall museum was virtually abolished amid controversy in 2000, to make way for office space. One of its few surviving displays — which proved too expensive to move — is an Allosaurus dinosaur excavated by one of the last Princeton undergraduate expeditions, a trip to Utah in 1941.

Princeton’s famed Vertebrate Paleontology Collection, which ranged from fish to mammals, was viewed as taking up too much storage space in Guyot and was given away in 1985 — including the Uintatherium skulls from the badlands. In a historical irony, the collection went to join the materials of Professor Marsh at Yale’s Peabody Museum. Meanwhile, dinosaur mania seemingly will never end: Casting is underway for another Jurassic Park sequel, to be called Jurassic World, due in theaters in 2015.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is a lecturer at the University and author of six books, including Princeton: America’s Campus.

2 Responses

Mark L. Holmes ’60

10 Years AgoThe Museum in Guyot

I enjoyed the article “Tigers and Dinosaurs” (feature, Nov. 13), although it brought back painful memories of the shortsighted decision by the administration in 2000 to evacuate the Guyot Hall museum in order to “make way for office space.” To an institution like Princeton, history counts for much, and much history was destroyed by that thoughtless action. Temporary office space, surge space if you will, can be readily found at any university while new construction is planned, funded, and completed. I found this out firsthand in my involvement with capital projects here at the University of Washington. It was a total lack of both short- and long-term planning on the part of the administration that led to closure of the museum.

Lincoln Hollister

10 Years AgoThe Museum in Guyot

When the museum closed its doors in 2000, alumni were told that the museum specimens would be returned to a new and better museum, which would be constructed in the near future. Much of the contents of the museum, carefully packed up for the return, are still in storage.