Toward a Greener Princeton

In its most recent report, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), reflecting the views of scientists around the world, declared that “warming of the climate system is unequivocal.” It left no doubt that unless greenhouse gas emissions are reined in, the ecosystems that sustain humankind and the animal and plant life that we know today will be irreparably harmed.

As one of the world’s foremost centers of climate science and as an institution committed to serving all nations, Princeton has a critical role to play in exploring the causes of climate change, evaluating its effects, and developing solutions to the environmental, technological, and socioeconomic challenges it represents. Indeed, a key component of our newly launched Aspire campaign involves bolstering the work of the Princeton Environmental Institute, the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and their campus partners, allowing our University to play an even more effective role in the search for a sustainable future. This is clearly where Princeton can have its greatest impact. At the same time we also have an obligation to put our own environmental house in order—to practice what we preach. With a 380-acre main campus, more than 160 buildings, and some 12,500 students and staff, we can ourselves become a laboratory in sustainability, implementing best practices, testing new technologies and strategies, and reducing our environmental footprint in a way that complements—and furthers—our academic efforts in the environmental arena.

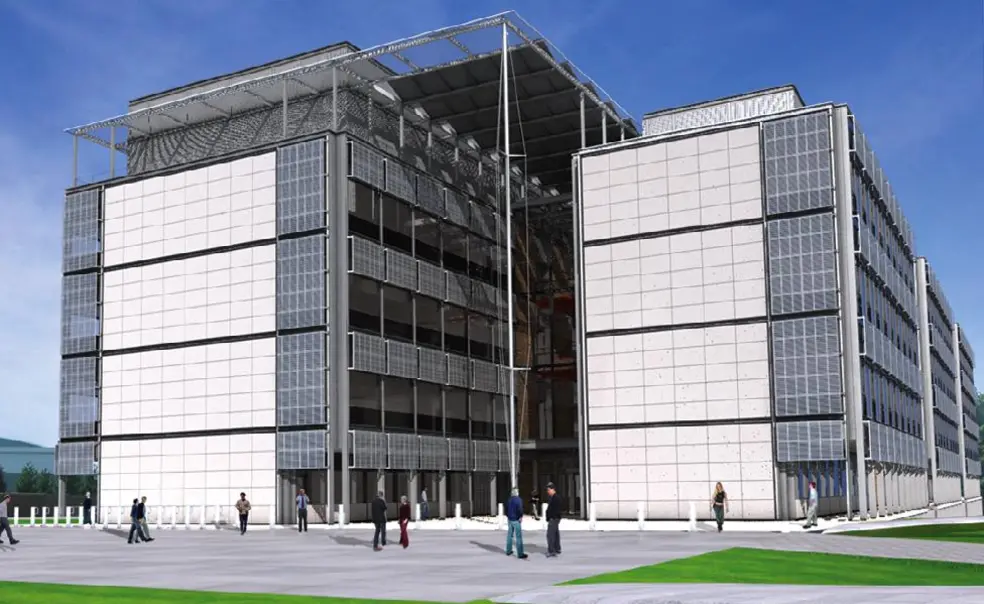

Our University has a long tradition of environmental stewardship, and, in recent years, we have taken a number of important steps to increase the efficiency of our heating and cooling systems and to reduce electrical consumption. The cogeneration plant, completed in 1996, and a large chilled water tank, installed in 2005, have given Princeton one of the country’s most efficient and cost-effective central power facilities. Our new 10-year campus plan commits us to developing the campus in an environmentally responsible manner while adding two million square feet in new construction. To this end, we have developed a set of “sustainable building guidelines” for architects and engineers, touching on everything from building materials to waste management practices.

In a host of ways, our faculty, staff, and students are conserving natural resources and protecting the environment, whether that means fixing leaky steam traps, consuming locally grown produce, or participating in the annual 10-week RecycleMania competition that now includes some 400 colleges and universities (last year we outdid both Harvard and Yale and ranked second in New Jersey in recycling and solid waste reduction). None of this, of course, would have been possible without the enthusiastic and persuasive leadership of the Princeton Sustainability Committee, representing all sectors of our University community, the student organization Greening Princeton, and our new Office of Sustainability

under the direction of Shana Weber.

Although much has been accomplished, there is a consensus that we need to do more. Executive Vice President Mark Burstein has spearheaded the development of Princeton’s first-ever sustainability plan (www.princeton.edu/pr/reports/sustain/), which commits the University to forcefully advancing its environmental agenda in three major areas: greenhouse gas reduction, resource conservation, and research, education, and civic engagement. Under this plan, our most ambitious goal will be to reduce campus greenhouse gas emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, notwithstanding the intervening—and substantial—growth of our campus, and to do so without the purchase of “offsets,” which allow the purchaser to avoid emission reductions by paying for environmental improvements elsewhere. By further enhancing our central power facility, retrofitting existing buildings, using half as much energy in new or renovated structures as required by the current energy code, and applying a voluntary “CO2 tax” to new construction and renovation projects (thereby justifying in a cost benefit analysis more expensive energy-efficient designs and technologies), we will be able to prevent 75,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere in 2020 and every year thereafter. By that time we also intend to achieve a 10 percent reduction in the number of cars commuting to campus, thanks to improvements in public transportation, an expanded shuttle system, support for telecommuting, and other strategies.

Our plan also calls on us to continue Princeton’s strong commitment to conserving resources, including a 25 percent reduction in personal water use per student by 2020 and a far-reaching storm water management program that will lessen demand for water and support our region’s watershed. Other goals include further reductions in solid waste through more aggressive recycling, the adoption of 100 percent recycled disposable paper products (Princeton moved to 100 percent recycled paper for general office use in 2004), the universal use of environmentally friendly cleaning products, and a substantial increase in the percentage of sustainably produced food that we consume. Finally, with generous support from the High Meadows Foundation, the plan invites us to foster an even greater level of research, education, and civic engagement in the environmental field, including support for faculty, student, and staff initiatives that “use the campus as a dynamic hands-on laboratory for studying and testing innovative approaches to sustainability.”

Princeton’s new sustainability plan is not a static document but a launching pad for a greener future, with annual goals and metrics that will keep us focused on the prize: a University with a global environmental vision that begins—no ifs, ands, or buts—at home.

No responses yet