Trustees Vote to Divest and Dissociate from Fossil Fuel Companies

The University will cut all ties with 90 companies, including Exxon Mobil and Dominion Energy

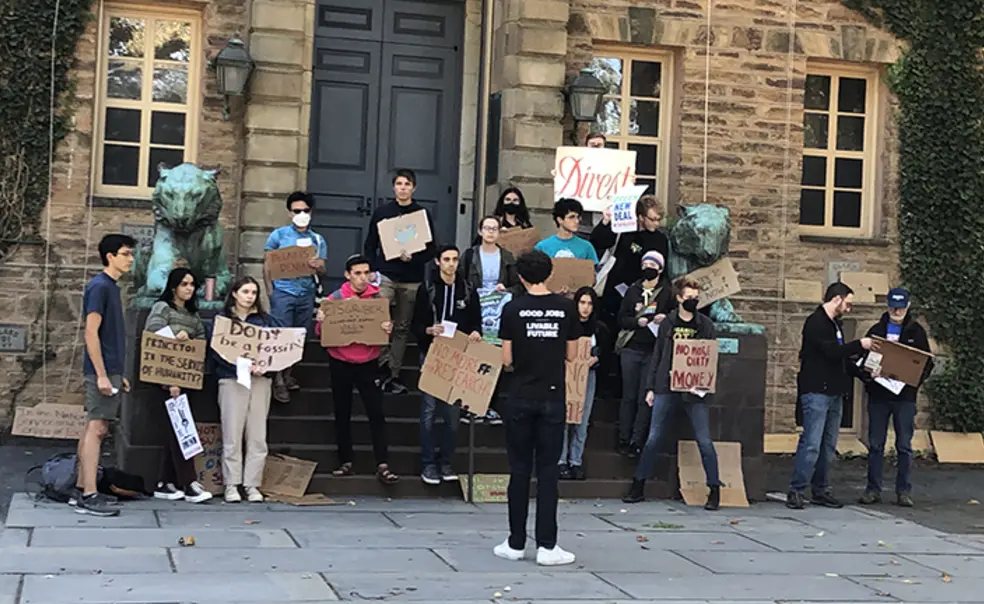

When Princeton announced it was divesting from fossil-fuel stocks and dissociating from some of the industry’s worst polluters — a move that was years in the making — many students, faculty, and activists celebrated the news.

“Princeton’s dissociation decision is the culmination of an unusually thoughtful, transparent, and deliberative process,” Dean for Research Pablo Debenedetti told PAW via email.

The Board of Trustees voted in September to divest the endowment from all publicly traded fossil-fuel companies and dissociate from 90 fossil-fuel companies, including Exxon Mobil and Dominion Energy, that are active in the thermal-coal or tar-sands business. (The full list is available at fossilfueldissociation.princeton.edu.)

The steps come more than seven years after the Princeton Sustainable Investment Initiative submitted a proposal calling for the University to divest from coal companies and eventually end its investment in other fossil fuels. Divest Princeton, a group of students and alumni, revived the effort with a proposal to the Council of the Princeton University Community (CPUC) in 2020.

The CPUC’s review eventually led to the board announcing in May 2021 its intention to dissociate from, or cut all business ties with, companies engaged in climate disinformation and those that participate in the thermal-coal and tar-sands segments of the industry. The move was finalized this September, though the trustees determined that no companies currently meet the “exceedingly high” bar for dissociation based on disinformation practices.

According to a University announcement, the board has committed to “a net-zero endowment portfolio.” The Princeton University Investment Company (Princo) will eliminate its fossil-fuel holdings and “ensure that the endowment does not benefit from any future exposure to those companies.”

“The actions taken by the University and the Board of Trustees are a huge step towards the full divestment and dissociation from fossil fuels,” Divest Princeton co-coordinators Nate Howard ’25 and Aaron Serianni ’25 told PAW by email. “This decision is the result of a decade of activism by Princeton students, faculty, staff, and alumni.”

“This decision is the result of a decade of activism by Princeton students, faculty, staff, and alumni.” — Divest Princeton co-coordinators Nate Howard ’25 and Aaron Serianni ’25

In March, Princeton announced — for the first time — dollar figures that detailed the University’s investments in fossil fuels: a total exposure of about $1.7 billion, or 4.5 percent of the endowment. The University’s Faculty Panel on Dissociation Metrics, Principles, and Standards issued a report in May that recommended criteria for dissociation. Minor revisions were incorporated from an administrative committee — which included Debenedetti — before it was passed on to the board, but the board was not required to adhere to it.

Members of the faculty panel told PAW via email that they were pleased to hear about the trustees’ vote.

Professor Michael Oppenheimer, a member of the faculty panel, said it was “a major step forward for Princeton and for corporate accountability.” Though he felt the decision left “undone” one key aspect, sanctions against companies that propagate disinformation, he also said that “the policy is a work in progress … and can point the way for other universities as well as Princeton.”

Anu Ramaswami, chair of the faculty panel, said she agrees with the trustees’ decision not to take action against those engaging in climate-disinformation at this time, and that the vote “opens up new frontiers in higher education’s efforts to advance sustainability.”

Author and activist Bill McKibben was among the environmentalists who applauded the news on social media. “Truthfully, Princeton took an awfully long time to grapple with this most important of issues, but I was happy to see them divest, and actually impressed to see them looking at the consequences of funding relationships with big oil, which breaks some new ground,” he said in an email to PAW. “Above all, it made me very happy to be able to say that Exxon no longer had that tiger in its tank.”

In 2020, Exxon Mobil renewed a partnership agreement with the Andlinger Center that is scheduled to run through 2025. The University said it will create a fund to offset research resources lost because of dissociation.

Princeton is currently communicating with the identified companies, and in its announcement noted that “if a company provides information in a timely manner that resolves the concerns or demonstrates changed behavior moving forward, it could be exempt from dissociation and removed from the list.”

It is unclear exactly when Princeton plans to dissociate.

“We’re grateful to the Princeton faculty members who dedicated their time and expertise to addressing an important and challenging set of questions,” Board Chair Weezie Sams ’79 said in Princeton’s announcement. “It is thanks to their work, and the engagement of many members of the University community, that we’re able to take these steps today.”

When the University revealed its fossil-fuel holdings earlier this year, about $13 million, or 0.03 percent of Princeton’s endowment, was held directly in fossil-fuel investments, while the rest of the exposure was held indirectly (for example, through external managers). At that time, the University’s endowment did not include any companies that derived more than 15 percent of revenue from tar sands, while about $19 million came from companies that derived more than 15 percent of revenue from thermal coal.

13 Responses

Allan Demaree ’58

2 Years AgoHighlighting an Exxon Investment

Recent news that Exxon Mobil will invest nearly $5 billion to reduce carbon dioxide in the environment illustrates the manifest silliness of the trustees’ decision to dissociate from the company (On the Campus, November 2022). Exxon is buying Denbury, a pipeline operator that moves CO2 from smokestacks to underground reservoirs. To put that investment in context, it comes to nearly 14 percent of the value of Princeton’s endowment. Altogether, Exxon says it will spend $7 billion on low carbon businesses by 2027 and $10 billion to curb its own emissions.

Critics will doubtless berate the company’s actions as “greenwashing.” Professors of Economics 101 might remind them that market-driven corporations respond to signals from consumers (who need gasoline) and governments (which subsidize public goods like carbon capture). They do not respond to virtue signaling by university trustees. Will the trustees now remove Exxon from its naughty list? And how much of Princeton’s resources, financial and intellectual, are being frittered away in the pointless search for culprits thought to warrant dissociation?

Evelyn Bolin *89

3 Years AgoInternational Alternatives to Divestment

While the University’s Board of Trustees may have done the appropriate thing for the University and its stakeholders by divesting wholesale from all fossil fuel-producing companies in one sweeping move, it should be recognized that this is not the correct move for all investors around the world. In South Africa, where I have lived and worked for the past 25 years as a financial/economics writer, with its population of around 158 million, the economy is heavily dependent on coal as an energy source, accounting for around 80% of all energy production and directly employing some 93,000 people in coal mining (the U.S., with its population of 333 million, employs around 60,000 people), and another 250,000 work in the local oil industry. A sudden halt to the provision of capital to coal producers would bring the country to its knees. That is why the SA government and local investors have adopted a “just transition” approach, focusing on the gradual introduction of green energy sources in cooperation with the private sector. Investors are facilitating fossil fuel companies in their transitions, so that their cost of capital for implementation doesn’t become too onerous. While all would agree that there must be an end to the use of fossil fuels to produce energy and stop global climate change, there is no “one size fits all” approach to this transition, and this should be recognized by global investors. Their divestment could come with very real and destructive consequences for others.

Ben Beckley ’03

3 Years AgoContinuing Divest Princeton’s Fight

A few reactionary alumni have criticized members of the broad and burgeoning divestment movement for failing to free ourselves from gas-guzzling cars and single-use plastic (Inbox, December issue and PAW Online). It’s true that the proliferation of fossil fuels touches nearly every aspect of modern life, just as slavery’s economic impact was once inescapable — even for white abolitionists in their starched white cotton shirts.

What’s also true, as I write this on a 70-degree day in late fall in Astoria, New York, is the severity of the worsening climate crisis and its underlying causes. In 1965, the American Petroleum Society told its members that carbon dioxide would produce “marked changes in climate” by the year 2000. The fossil fuel industry has known for more than half a century the havoc it would wreak on people’s lives.

In those 50-odd years, the industry has not only sought to hide its own culpability, but waged a relentless public relations campaign, full of spurious arguments against the growing number of concerned citizens it considers its enemies. Twenty years ago, for instance, when British Petroleum began heavily promoting the term “carbon footprint,” the company did so to shift blame from corporate malfeasance to individual lifestyle choices.

Note that BP is unfortunately and inexplicably missing from the list of companies from which Princeton has committed to dissociate. For alumni truly committed to the “service of all nations” — and for anyone worried about famine and drought, fires and hurricanes, rising temperatures and rising seas — we need to keep fighting.

Alexander D. Jung *57

3 Years AgoSupport for Divestment Decision

I am a 1957 graduate (M.S.E.) of the program in plastics engineering, which at the time was the only graduate course in the U.S. for the subject of high polymer engineering. Louis Rahm and Bryce Maxwell directed the plastics laboratory, and they catapulted me into a highly successful professional career as a result.

The purpose of this letter is to compliment Princeton on another matter — that of the announcement (PAW, November 2022) that the University was divesting and dropping endowment holdings plus cutting all ties to 90 companies in the business of fossil fuels.

I am ashamed to have to admit that as a successful high polymer chemical engineer I was part (unwittingly) of what has transpired since I graduated in the 1950s. My only excuse is that in those days the problems with the fossil fuels and polymer waste did not exist.

Please convey my compliments to the president and trustees on their actions. I’m in full support.

Allan Demaree ’58

3 Years AgoShunning (While Benefitting From) Fossil Fuels

Re “Princeton Divests” in the November issue: The University’s newly adopted policy of dissociating from fossil fuel companies it disagrees with calls to mind the Puritan practice of shunning (The Scarlet Letter, anyone?). But there’s a difference. In Princeton’s case, the shunners continue to benefit from the sins of the shunned. Our trustees will keep driving, flying, heating and cooling their homes, and plastic-wrapping their leftovers — all while ostracizing those whose labors make these amenities possible. They can’t know whether a gallon of gas they buy at the pump originated in a well drilled by Exxon Mobil, which they have decided to shun, or one drilled by BP, Chevron, or Saudi Aramco, which they haven’t (yet). Meanwhile, since Exxon’s (perfectly legal) practices are unlikely to change, the company will continue adding to world supply, making it a tad cheaper for Princeton’s hierarchs and the rest of us. Is the University’s decision to dissociate the definition of hypocrisy, or what?

Larry Moffett ’82

3 Years AgoThis Brings Back Memories

I remember when I was at Princeton, walking past Nassau Hall there were often students marching and chanting “Divest!” to demand that the University divest from companies doing business in South Africa under the apartheid regime. Although I felt some sympathy for their cause, I thought they were too radical and idealistic. Now in retrospect I recognize they were on the right side of history, just as the students of Divest Princeton will be on the issue of fossil-fuel investments.

Entering Princeton at the time of the 1970s oil crisis (when oil reserves were wrongly forecast to run out in 20 years), I chose to study mechanical engineering because I wanted to work on solar energy. After graduation, much to my disappointment I was unable to find a job in that field. (Energy companies advertising their research and development on photovoltaics and solar thermal collectors were engaged in an early form of greenwashing.) So it’s taken around four decades, but climate change has finally led us to acknowledge the urgency of ending fossil-fuel extraction and use, and making the difficult but crucial transition to renewable energy.

Robert L. Herbst ’69

3 Years AgoA Pleasant Surprise

Having attended President Christopher Eisgruber ’83’s State of the University program at Reunions last spring, at which he professed himself opposed to fossil-fuel divestment, I was unprepared for the trustees’ decision to divest, which I vigorously applaud (On the Campus, November issue). Hats off to Divest Princeton and its students, faculty, administration, and alumni supporters who these past years raised awareness with their advocacy, and to the Faculty Committee, which championed divestment despite the limited charge it was originally given.

It would have been interesting to be a fly on the wall during the trustees’ discussions leading to their decision. I have never understood why the board operates with such little transparency, especially with respect to major decisions like this one.

Robert Johnston *70

3 Years AgoWhat About Fossil Fuels Asset Managers?

Does endowment divestment include divestment from the asset managers holding or investing a trillion or so in fossil fuels?

Richard Byer ’82

3 Years AgoFollow Up Article: The Unintended Consequences of Divestiture

I would like to see a discussion on the unintended consequences of divestiture in fossil fuels and the impact on all of the other industries that rely on this product — perhaps a discussion on what happens when you require an entire industry that supports 10.3 million jobs in the U.S. and accounts for nearly 8 percent of our GDP to scale down, as opposed to an industry that typically scales up to achieve economies. Can we assume in our calculations that all other products that derive their existence as a result of their dependency on this industry will remain the same? Some might argue that with a greater supply, the price of this industry’s product would decrease. We should see the math.

Once you go down this path, you’d better have a plan in place when a natural disaster wipes out your solar or wind farm, servicing homes and businesses for millions of people.

Clark Irwin *78

3 Years AgoAn Irrational Gesture

Divesting assets related to fossil fuels is irrational and likely destructive of the values that prompt it. Shares already issued are merely changing hands, not depriving the issuing companies of any capital. Further, the people or institutions to whom the divested shares are sold are likely indifferent or even hostile to the value system of divestment zealots, so the shareholder/agent voting pressure on corporate governance could actually diminish.

Also, assuming that companies do not seek, produce, market, or use fossil fuels as a hobby or as an obsessive-compulsive exercise, their activity simply reflects the fact that people need or want their products. Why leave consumers off the tantrum-driven hit list?

To be logically consistent and to maximize the virtue-signaling aspect of divestment, therefore, Princeton should be equally committed to refusing to admit, hire, or retain anyone who drives a gasoline-powered car, heats with anything other than lunar power, has a polyester shirt or blouse in the closet, uses a solar panel that has any fossil-fuel DNA in its production chain, keeps their leftover kale-and-quinoa salad in a plastic container, assimilates their faux-moralistic view of the world through plastic-lensed and -framed eyeglasses, or uses a plastic-cased pen to sign divestment petitions, and so forth.

If the Fates are kind, these trendy episodes of outrage will eventually self-destruct like a lithium battery exposed to air, but in the meantime, they are pathologically interesting.

Ben Beckley ’03

3 Years AgoA Rational Response

In last week’s PAW, Clark Irwin attempts a haphazard assault on fossil fuel divestment. His ad hominem criticisms of the broad and burgeoning divestment movement careen from pseudo-scientific psychobabble (“irrational,” “zealots,” “obsessive compulsive,” “pathologically interesting”) to condescending paternalism (“hobby,” “trendy,” “tantrum-driven”). I wonder whether Mr. Irwin has considered whether words like “irrational” and “tantrum-driven” might apply more aptly to a certain former U.S. president who has denied the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change.

At any rate, Mr. Irwin eventually turns his attention to accusations of hypocrisy. No one, apparently, has informed him that petitions are typically signed online nowadays, not with “a plastic-cased pen,” and that few of us still wear “polyester shirts.” But never mind that. It’s true that the proliferation of fossil fuels touches nearly every aspect of modern life, just as slavery’s economic impact was once inescapable — even for white abolitionists in their starched white cotton shirts.

What’s also true, as I write this on a 70-degree day in late fall in Astoria, New York, is that Mr. Irwin utterly fails to address both the severity of the worsening climate crisis and its underlying causes. In 1965 — the year before Mr. Irwin entered Bowdoin College — the American Petroleum Society told its members that carbon dioxide would produce “marked changes in climate” by the year 2000. The fossil fuel industry has known for more than half a century the havoc it would wreak on people’s lives.

In those fifty-odd years, the industry has not only sought to hide its own culpability, but waged a relentless public relations campaign, full of spurious arguments much like Mr. Irwin’s, against the growing number of concerned citizens it considers its enemies. Twenty years ago, for instance, when British Petroleum began heavily promoting the term “carbon footprint,” the company did so to deflect attention from corporate malfeasance and to shift the blame to individual lifestyle choices.

Note that BP is unfortunately and inexplicably missing from the list of companies from which Princeton has committed to dissociate. For alumni truly committed to the “service of all nations” — and for anyone worried about famine and drought, fires and hurricanes, rising temperatures and rising seas — we need to keep fighting.

Cory Alperstein ’78

3 Years AgoSing the Praises of Student Changemakers

“Princeton will have the most significant impact on the climate crisis through the scholarship we generate and the people we educate,” said President Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83.

I agree generally with President Eisgruber and would say that an institution that celebrates the commitment of its students to consistency regarding “cause and effect” is truly preparing its students to address the challenges of the world. Change comes about because a few people decide not to accept the status quo and choose to do the work of change. They gather support and find ways to be heard. They try persuasion on the inside, and push from the outside to expose and protest. As urgency grows, changemakers are joined by others who see the necessity for action.

Princeton should be proud of the determination of Princeton undergrads, grad students, and alums over the last five years who wouldn’t let “no” stand, who called out delay tactics and literally educated administration and trustees on the inextricable link between Princo investments and the intellectual products of academia. The president, representing the administration, should acknowledge and celebrate the role of Divest Princeton, and that of changemakers generally at an institution that generally presents its decisions as top down. Such acknowledgement wouldn’t weaken the decisions of the administration, it would reinforce and strengthen them.

As an alumni supporter of this group I have been floored by the intelligence and moral dignity of members as they have researched, proposed, partnered, informed, called out and dragged this institution forward to do what it has known for far too long that it must do. They are the best Princeton has to offer to a world that is standing at the brink. Without smart, moral, loyal, and determined students, Princeton trustees would not have moved forward on divestment and dissociation. And yet in its formal statement the administration said not one word about Divest Princeton. Let’s hear the administration sing their praises. Divest Princeton is still working — there is more to do.

Richard Waugaman ’70

3 Years AgoNo Wonder Princeton is Still Number 1!

What wonderful news! Princeton continues to set a fine example. And all of us can be inspired to follow Princeton's example in fighting climate change. My wife and I just had solar panels installed on our roof.