Tutors Behind Bars

For a decade, the Petey Greene Program has been sending students into prisons

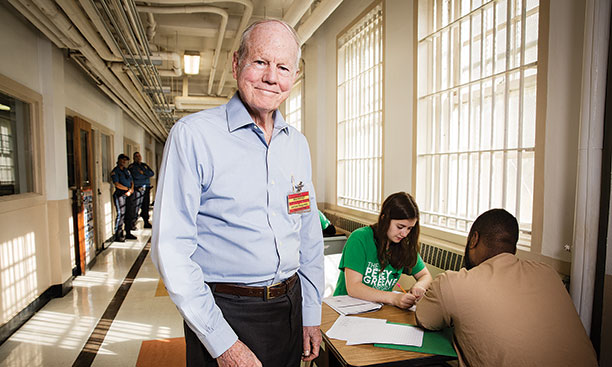

Jim Farrin ’58 is on a mission, and it begins almost every morning with a visit to a van parked outside Firestone Library. There, Farrin cheerily sends Princeton students off to prison.

Farrin is the executive director of the Petey Greene Program, a Princeton-based nonprofit that is celebrating 10 years of providing free tutors for the imprisoned to help them pass high-school equivalency tests and meet other academic goals.

It’s a mission that began with a perhaps unlikely friendship.

In the mid-1960s, Charles Puttkammer ’58 was working for the United Planning Organization, an antipoverty program in Washington, D.C., and was asked to sit in on meetings with Ralph Waldo “Petey” Greene, who had been imprisoned for armed robbery but upon release was hired by the UPO to administer a program for other recently released prisoners. Puttkammer took a liking to Greene, who he said had a “gift for gab” and was one of the most intelligent people he had ever met. He encouraged Greene to take speaking engagements, which led to Greene’s hosting a radio talk show and then a TV show. By the time he died of cancer in 1984, Greene was a celebrated community activist.

In 2007, after Puttkammer’s investment in a company that provided nursing-home services left him with “a considerable amount of money,” he decided to honor that friendship. He came up with an idea inspired by his father, a professor of criminal law in Chicago, and by a project he had taken part in as a Harvard graduate student in which students (including his future wife) volunteered in a psychiatric hospital.

Puttkammer called classmate Farrin, whose career was in sales and marketing but who had written his Princeton thesis on a judge who promoted rehabilitation of inmates. Would Farrin consider launching a nonprofit that would send Princeton University students into prisons as tutors?

Farrin said no.

But the next day, Farrin’s wife, Marianne, a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary, attended a reunion there and met a chaplain from the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility outside of Trenton. He said the prison needed tutors for its education program. Long story short: Farrin saw it as a sign. He called Puttkammer to say he was on board. The first Petey Greene Program tutors went to the Wagner facility in a pilot program in spring 2008.

A decade later, Petey Greene, as the program is known, is in eight states, has 21 full-time and two part-time employees, and works with students at 29 universities and colleges in 37 correctional facilities. In 2017, 892 college students and community volunteers tutored in prison and jail classrooms. The goal is to expand nationwide in the next 10 years, and the staff is gathering metrics to attract additional sources of funding. Currently Puttkammer, through the Rockefeller Foundation, provides about 53 percent of the $1.5 million annual budget.

Recognition of the program is growing nationally. In October, Farrin received AARP’s $50,000 Purpose Prize, which recognizes individuals who use their life experience to make a better future for all.

University ties have also increased. From the start, Farrin partnered with the Pace Center for Civic Engagement to recruit volunteers. At their 50th reunion, members of the Class of 1958 selected the program as a project, and class members serve on the board of trustees. In 2015, Irwin Silverberg ’58 and his wife, Carol, gave $300,000 to establish an endowment fund.

More than 500 Princeton undergraduates and graduate students have served as tutors, including 101 in 2016–17.

Tutors learn the basics in an intense four-hour training session that includes discussions of cultural humility and privilege in terms of access to education. They refer to those they tutor as “students,” and to themselves as “tutors.” They commit to tutoring three hours weekly for 10 to 12 weeks, supplementing and supporting the paid, professional teachers employed by the prisons. A Petey Greene T-shirt and loose-fitting pants are their uniform, and their phones don’t leave the van. And tutors cannot ever be late for the van, which leaves twice a day from campus — including at 7:20 a.m.

Princeton students describe the tutoring experience as formative, inspiring careers in criminal-justice reform. In a recent survey of 250 program volunteers, half said tutoring had changed their academic or career focus.

Lawrence Liu ’16 remembers his first time at Wagner, an all-male prison, as a shocking experience: “The doors slam super loudly behind you. The walls are barren. It’s very uninviting.”

But discussing GED personal essays led to some personal connections for Liu. “Some of these guys have small kids or significant others they really care about,” he said. “You hear who they are, and start to see they are not so different than any of us.”

Liu is currently in a J.D.-Ph.D. program, planning to get a Ph.D. in jurisprudence and social policy at UC, Berkeley School of Law and a law degree at Yale.

Grace Li ’14 said she was “sort of a lost sophomore” before she joined Petey Greene; tutoring at Garden State Youth Correctional Facility “took me off campus and made me feel connected in a human way to those students.” After graduation, Li was hired by the program as a regional field manager, and then as monitoring and evaluation manager for the New York City area. She is now studying law at NYU and would like to work as a public defender or on criminal-justice reform.

Joseph Barrett ’14, who was also hired as a regional field manager after graduating, applauds the program for putting “young graduates in positions in which they can make small-scale changes.” The hope, he added, is for “large-scale change as people think about prisons and the roles they play in society.” Barrett started working last fall for the Center for Court Innovation, a New York-based nonprofit that aims to make the justice system more just, humane, and effective.

The program also changes lives for those behind bars. Petey Greene staff members cite a 2014 RAND Corp. study that found that prisoners who participate in education programs have a 43 percent lower chance of recidivism than those who do not.

Erich Kussman, whose mother was a drug addict and who dropped out of high school to sell drugs, was one of the first inmates tutored through Petey Greene 10 years ago. He was deeply struck by the fact that the tutors worked for free and “believed that people are better than the situations they were brought up in.” They inspired him to “dream big dreams,” he said, and without their encouragement, “I probably wouldn’t have continued my education.”

After starting college classes during his 12-year prison term, Kussman went to school full time and is now in his second year at Princeton Theological Seminary. He hopes to start a faith-based re-entry system as an alternative to New Jersey’s halfway houses.

Puttkammer said the Petey Greene Program is all about these kinds of second chances. He credits his own success in life to his parents and empathizes with those who don’t have that sort of support. “You have to treat younger prisoners the best way you can,” he said.

No responses yet