The architect who created the look of Princeton’s campus wrote ghost stories. Fittingly, Ralph Adams Cram’s stories are about haunted buildings, and what haunts those buildings is the past. In a story collection that he published in 1895, empty houses prove, over and over, to be anything but. In a crumbling castle near Innsbruck, Austria, where a devilish nobleman once set the ballroom on fire while his guests danced inside, two “ghost hunters” get caught up in a danse macabre. In a secluded convent near Palermo, Italy, a visitor follows a beckoning specter to the site where, a century earlier, the nuns bricked up one of their sisters in the convent’s walls, a heartless punishment for a sin of the heart. In an abandoned old manse in the Latin Quarter of Paris, rumored to have once been a favorite haunt of the city’s witches, a gang of young “rake-hell” students spends the night on a dare, with predictably ghastly results.

The thesis is straightforward: We inhabit buildings, and they inhabit us, in a larger sense than we might think. In 1907, a group of archaeologists who planned to do excavations in the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey performed séances to get advice from the former inhabitants on where to dig. Cram wrote a defense of their methods, arguing not that they dialed up literal ghosts but that buildings are a deep well of memory that outlasts their inhabitants. (The archaeologists found what they were looking for, but England is so crowded with historical odds and sods that they find kings under parking lots, so their chances were already good.)

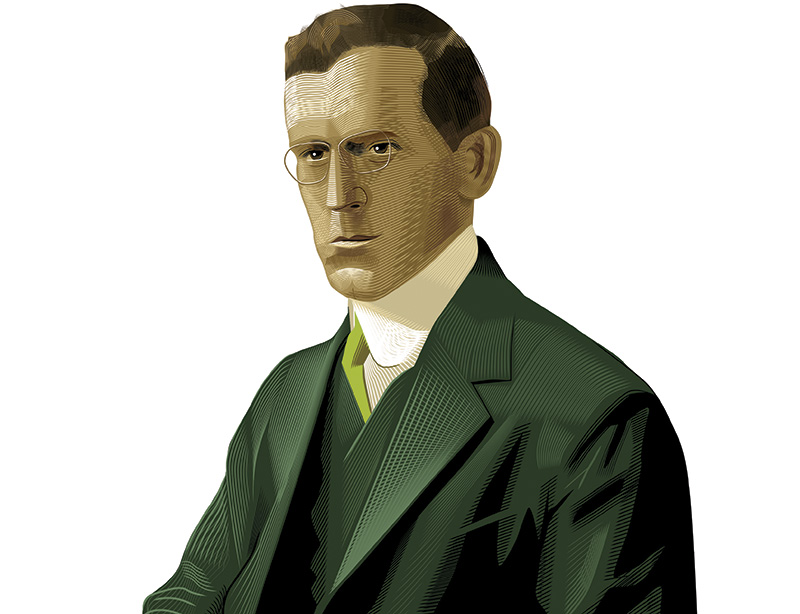

The son of a poet and a Unitarian minister, Cram spent his childhood in a series of posh New England private schools. As an adolescent, he read passionately the works of John Ruskin, an English architecture critic who, more than anyone else, inspired the Gothic Revival of the 19th century, arguing that the Gothic architecture of the Middle Ages — many-cloistered, profusely ornamented, imperfect, rich with ideas — allowed craftsmen to work with a degree of pleasure and creativity that modern architecture, straight and machine-perfect, denied them.

In 1907, a group of archaeologists who planned to do excavations in the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey performed séances to get advice from the former inhabitants on where to dig. Cram wrote a defense of their methods.

Cram became an architecture critic himself, and in that line of trade, he often rehearsed Ruskinian ideas — for instance, that an artist’s reach must exceed their grasp: “We must remember that, though it seems a paradox, the passion for perfection that fails is sometimes more noble than the passion for perfection that achieves.” He joined an architecture firm and became famous for building magnificent Gothic cathedrals, such as the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The New Yorker called him “seven centuries late.”

In 1907, the University hired Cram as its supervising architect. At the time, the buildings were “go-as-you-please,” in his term, as to site and style, following what each donor preferred: Greek here, Romanesque there, Venetian Gothic there. Cram built a unified campus out of this scramble, adding — in a Collegiate Gothic style that also emulated aspects of existing buildings — dormitories, lecture halls, the art and architecture school, the Graduate College, and finally, the Chapel. Building Princeton, he said, was “the greatest honor that has come to me in my professional career.”

In designing the campus after the model of Oxford and Cambridge, Cram sought to conjure a place out of time. But he also designed the campus to change. Stone paths appeared along “desire lines” that students trod in the grass. Wind and rain gave interesting new expressions to the faces of the gargoyles on the buildings. Cram liked the wear of time. He liked change and its marks. He wanted to be on both sides of the séance.

No responses yet