‘U.S. Crisis Monitor’ Tracks Political Strife, Seeks Peace

‘Jan. 6 was not the beginning. There were so many signs,’ says Shannon Hiller *15

In the months before a mob stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, Nealin Parker *08 and Shannon Hiller *15 were worried. Parker is the founder of the Bridging Divides Initiative (BDI), a research group that focuses on reducing political violence and building community resilience, at Princeton’s Liechtenstein Institute on Self-Determination; Hiller co-directs BDI with Parker. Together, they had been monitoring political violence and demonstrations across the country — and the trends were alarming.

“Jan. 6 was not the beginning. There were so many signs,” says Hiller.

A shift in the social psyche had moved out of dark corners of the internet and into real life with destruction of property and violence at political rallies. Between May and September of last year, for example, there were more than 100 incidents of cars ramming into Black Lives Matter protesters nationwide, and in December a BLM banner that had been stolen from a church in Washington, D.C., was publicly burned. In September, a self-proclaimed “antifa” radical shot and killed a Donald Trump supporter in Portland, Oregon.

“There’s a psychological jump from seeing a person who votes differently from you as someone you disagree with to someone who is evil and morally corrupt,” explains Parker, a lecturer at Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs who spent years working on violence prevention and post-conflict reconciliation in war-torn countries. Now, she recognized the same red flags in the United States that she had seen abroad. On top of that, she says, a growing distrust of the political system has led people to become “less likely to see that system as a justified arbiter of their discontent, and will feel themselves forced to take their frustration out in other ways.”

So, in July, as social-justice demonstrations swept across the U.S., and as the 2020 presidential election grew increasingly contentious, BDI, alongside its other projects, launched the U.S. Crisis Monitor, a seven-month-long project to track, mitigate, and prevent political violence.

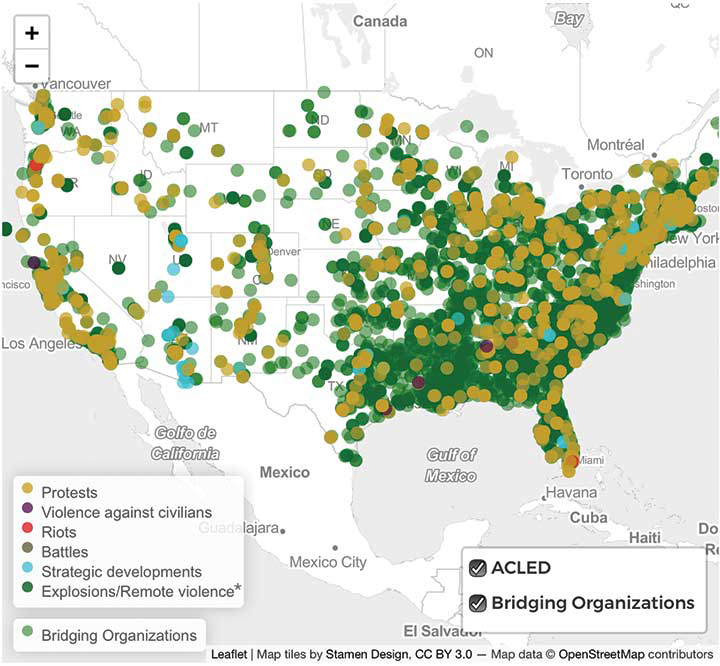

BDI partnered with the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), which provides real-time data on political violence and demonstrations culled from more than 1,500 sources and coded to include details such as locations, times, types of event, actors, and fatalities. The U.S. Crisis Monitor merged that information with BDI’s extensive database of social and governmental peace-building agencies, risk analysis, and tailored insights for key decision makers. The project produced tools such as the “Building Resilience Ecosystem Map,” which pinpoints areas of risk and couples them with the names and contact information of local organizations that can help. Parker describes the Ecosystem Map as “one-stop shopping” for individuals, organizations, and politicians looking to improve community safety and relations.

For example, a nonprofit that targets online extremism and misinformation recently contacted BDI for advice on where to focus its work. Parker says the Ecosystem Map helped it narrow its search to areas where there had been recent political riots and violence; then it could easily pinpoint the agencies that address misinformation and ideological division in those areas. “They can really quickly go from identifying an area where they want to work to then finding 10 people they can connect with there,” Parker says.

While the U.S. Crisis Monitor project ended in February, BDI continues to provide data for immediate conflict mitigation with the long-term aim of building community resilience and trust. Hiller says she hopes community organizations and politicians use BDI’s data, custom advising, and online tools — including the new Ecosystem Map and research reports produced by the U.S. Crisis Monitor — to reach out to one another and strategize on leadership and plans ahead of potentially fraught events.

“If we only react with an immediate security response, we miss tackling these long-term root causes,” Hiller says, noting that her team is advising both state and federal government officials on policies to address those root causes. “These ideologies and issues are things we need to tackle as a whole society, with a lot of community effort.”

It’s about more than just achieving the absence of violence, Parker says. “We’re trying to build sustainable peace.”

A U.S. Crisis, Mapped

Princeton’s Bridging Divides Initiative created this map in concert with the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. Their efforts, called the U.S. Crisis Monitor, came together in a seven-month project that combined both groups’ data from last summer until February. The interactive map, seen here, tracked various forms of domestic unrest, such as protests and riots, and offered information on peace-making organizations that could be found nearby.

No responses yet