How do you improve the Vatican Library, one of the grandest, richest, and oldest libraries in the world? By making it a little more Princeton.

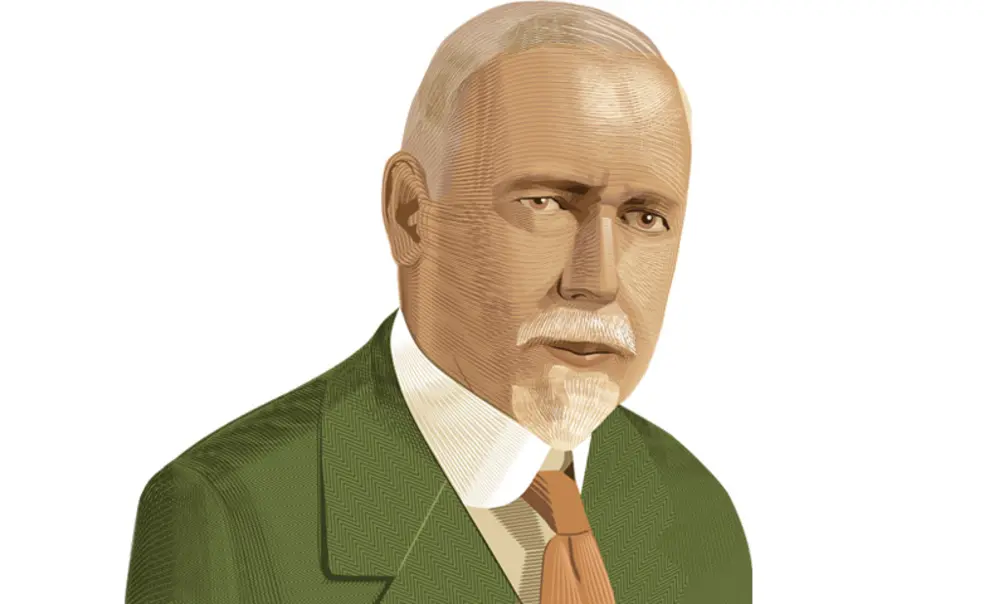

In 1926, the Vatican recruited William Warner Bishop, a librarian who honed his expertise at Princeton, for a task that he never expected they’d want an American to do: modernize the Vatican Library, which was founded in 1475 and still had a very medieval feel to its organization on every level, from cataloging to classification to shelf design.

As it turned out, American libraries had a reputation for innovative thinking, since they weren’t constrained by so many centuries of tradition. So the Catholic Church sought advice from leaders at the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress, who assured them that Bishop was the “doyen of American librarians.”

Bishop grew up in Detroit. He used to go to the library and stay there so long that he missed supper, for which crime — says his biographer, Claud Glenn Sparks — his mother “sentenced her son to a supper of bread and milk; but if grandmother Fannie Warner were at home, she commuted the sentence by making him an oyster stew.” Twenty years later, he was the head cataloger at the Princeton University Library, and he could stay in the bookstacks for as long as he wanted.

At Princeton, Bishop wrote catalog cards, fought with other librarians over how thorough cataloging should be (he favored very thorough cataloging), and helped to create new catalog rules for the American Library Association. The financier Junius Morgan, a nephew of J.P. Morgan, held an honorary post as associate librarian at Princeton, and the two of them bonded over book collecting and studying library architecture. For the rest of his career, Bishop’s ideas about library science were informed by Princeton’s history and traditions. “My experiences as head cataloger at Princeton,” he later said, “made me see and feel the library as a living organism.”

In 1907, Bishop moved to the Library of Congress, where he fetched books for Congress, the Supreme Court, and the White House. He found himself working again for Princeton’s former president, now the president of the United States. “At Princeton, Bishop had learned of Woodrow Wilson’s habit of reading mystery stories when he could not sleep at night,” Sparks says. “He was not surprised when the president personally telephoned him, asking that he send 10 detective stories a week to the White House. Bishop made the selections personally.”

When the Vatican Library asked Bishop for help, its state showed the difference between a great collection and a usable collection. (By then, he was working at the University of Michigan Library.) It held astonishing treasures: ancient scrolls, holy relics, grimoires said to be written by the Devil, papers holding the secrets of monarchs, popes, and saints. But it didn’t have a general catalog or consistent classification; the existing catalogs were incomplete and wildly irregular, some dating from the 17th century. The librarians were brilliant scholars but weren’t trained in modern library science.

After studying the library thoroughly, Bishop gave advice on seemingly every aspect of its organization, from bookshelves to classification to catalogs to catalog cases to shelving systems to the training of librarians to ventilation. The Italians objected to one piece of advice: that they compile a quick index of manuscripts for readers to use while they worked on writing a fully detailed catalog. Proud of their scholarly rigor and accustomed to taking the long view of the Church, they said they’d wait for the full catalog to be finished, even if it took a century.

Bishop liked to tell a story about a Kansas politician who complained about Kansas University’s asking for funds to buy books, saying, “Mr. Speaker, I object to spending this money. Why, they’ve got 40,000 books there at Lawrence now, and I don’t believe any one of them professors has read ’em all yet!” Scholars at Princeton and the Vatican surely haven’t read through those libraries, either, but now, at least, they can try.

No responses yet