Giving a voice to underrepresented communities through art has always been a priority for Daniel Heyman, a painter and printmaker who since 2010 has been a lecturer in the visual arts. His latest project, “In Our Own Words: Native Impressions,” is no exception. In June 2015, Heyman and Lucy Ganje, an art professor at the University of North Dakota who grew up on a nearby American Indian reservation, traveled to four reservations in North Dakota where they heard stories of languages lost, family traumas spanning generations, and the ongoing loss of Native American land, incorporating those stories into portraits. They saw how despite those losses, people on the reservations are dedicated to improving life for their communities — a man on the Standing Rock reservation ran for Congress, for example, and another leader proposed that the tribe establish a hardware-supply store so that the reservation could benefit from nearby oil-industry construction.

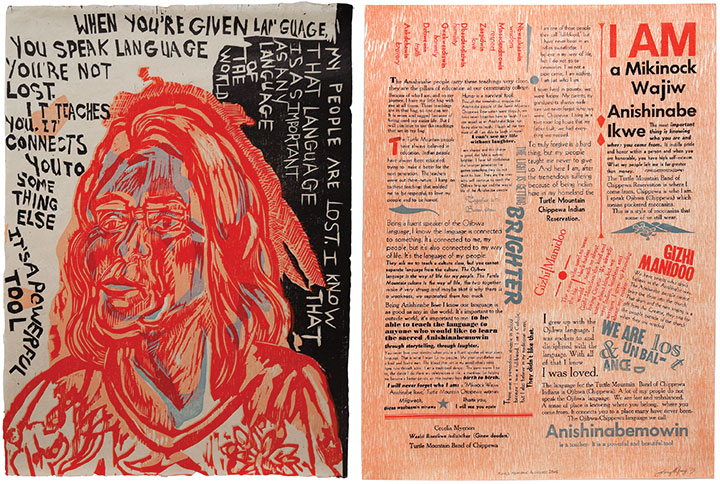

Heyman and Ganje spent several days at each reservation, beginning the woodcut portraits and interviewing the subjects. The interviews are integral to the project; Heyman carved excerpts around the subjects’ silhouettes while Ganje transcribed the interviews onto the letterpress prints that accompany the portraits. There are 12 woodcuts, 12 letterpress prints, and two combined technique prints. The works will be included in the exhibition “Hear My Voice” at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts from August 2017 to February 2018.

Heyman hopes that the project will give the public a “better understanding for who we all are as Americans.”“Native Impressions” is the most recent in a series of sociopolitical portrait projects by Heyman; he also has worked with victims of the shooting of civilians by Blackwater security guards at Nisour Square in Baghdad in 2007, former detainees of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, survivors of military sexual assault, and African American fathers trying to reconnect with their children after being released from prison.

“I’ve chosen communities that have been talked about endlessly in the U.S. body politic without ever really being asked directly, ‘What do you guys think about this?’” he says. “We simply asked, ‘Can you tell us about how you were arrested and what happened in prison? Can you tell us about your interrogation?’”

Later this year, Heyman hopes to travel to the Arctic Circle to interview native communities along the shores of Alaska and northern Canada that are feeling the effects of global warming. He’s teaching or co-teaching three courses on campus this spring and hopes that making art will allow his students to better examine the ways they perceive the world.

“I hope they learn to use art to engage the world around them, be it politics or some other concern,” he says.

No responses yet