Wanted: More Veterans

Princeton hopes reinstating transfers will bolster its recruiting efforts

Princeton’s decision to reinstate a transfer program in 2018 may help the University accomplish something it has tried to do for years: recruit veterans as undergraduates.

Veterans are among the groups Princeton is targeting in its efforts to increase student diversity. In an interview before the policy was approved, Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye said a transfer option could benefit veterans because many have completed some college courses during their service.

Princeton has not been successful in recruiting many veterans so far: Today, only one veteran is enrolled as an undergraduate. “We are doing everything we can in the environment we’re in right now,” said Rapelye. The transfer program would allow Princeton to “shift our focus to be able to talk to more veterans.”

Rapeleye said Princeton has been recruiting at military bases on the West Coast. In 2013, the University joined the federal Yellow Ribbon Program, which offers tuition assistance (in addition to the federal grant generally provided to veterans), and Service to School, a nonprofit organization that provides guidance to veterans applying to college.

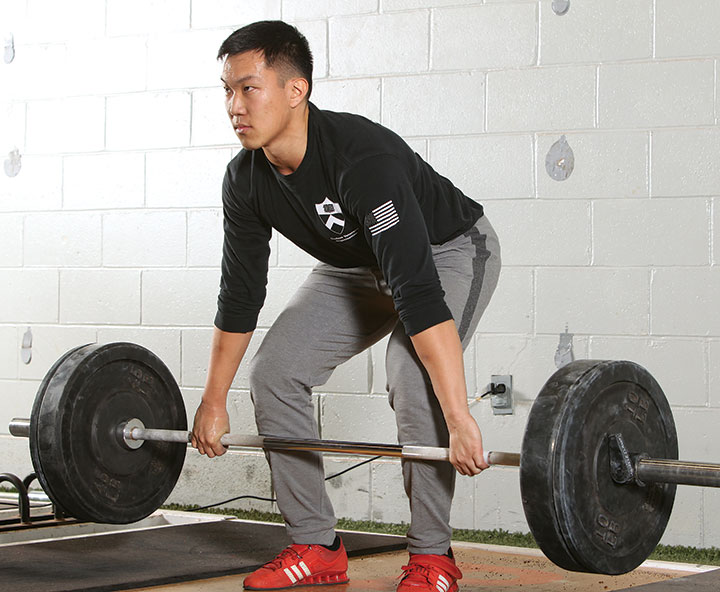

Mike Liao ’17, who served five years in the Marines as an air-support officer in Okinawa, is the only known undergraduate veteran at Princeton. The 25-year-old electrical engineering major suggested that the gap between high school and college has led to challenges his classmates may not face. “I have to spend a lot of time going over concepts which are very mechanical or trivial in nature to many of my peers,” he said. He has found that physical outlets — weightlifting and a conditioning program — also help his mental toughness.

Asked about Princeton’s support in his transition back to academic life, Laio said: “I can understand how some people might need help integrating back into the civilian world ... but I try to be independent and figure things out on my own.”

Liao suggested that accepting transfer credits will not be sufficient to attract veterans. “Most people in the military don’t think, ‘When I get out, I’m going to apply to Princeton,’ mainly because they think that it’s out of their league,” he said. “In a lot of cases, these are people who have never applied to college before, so they don’t understand what the process entails.”

More veterans are enrolled in graduate programs, including 14 at the Woodrow Wilson School.

Robert Hutchings, a visiting professor at the Wilson School and a former naval officer, said a stronger military presence on campus would bring a wider variety of perspectives into the classroom.

“Our country has been nearly constantly engaged in a war for most of the last two decades,” Hutchings said. “Students need to understand, consider, and debate these conflicts. ... If the debate is conducted almost exclusively among faculty and students who have never served in the military, there is something missing.”

Enrollment of veterans at other elite schools varies, with four reported at Yale and more than 400 at Columbia’s School of General Studies.

3 Responses

Drew Davis ’70, Jim Marshall ’72

9 Years AgoSupporting Veterans

We and many other veterans of military service in the Princeton community were heartened by the news that the University is elevating its efforts to increase the diversity of the undergraduate classes by recruiting veterans (On the Campus, April 6). While other selective universities have, since the attacks of 9/11, actively sought to matriculate the best and brightest of the 1.5 million young enlisted veterans of the “Long War” against terrorism, Princeton has lagged. To support the University’s new initiative, we are in the planning stages of forming what might be called the Princeton Veterans Association, or P-VETS. Our goals are to:

Other universities have succeeded in this effort. With Princeton’s commitment to “the nation’s service,” we can, too.

Ben Fuller ’67, LT USNR, EOD, Vietnam 68-70

9 Years AgoI’m in...

I’m in. How do we find out about the effort? How can I help? Long time coming. If Princeton is to really be in “the nation’s service” it needs to go beyond Wall Street.

Sgt. Zachary Jaynes, 75th Ranger Regiment

9 Years AgoAs an active duty soldier...

As an active-duty soldier eager to prove the positive impact of veterans on campus, I am very interested in this program at Princeton. Any further details or contact information for this initiative would be greatly appreciated.