A War’s Legacy

A half-century after the escalation of the war in Vietnam, a historian takes stock

Fifty years ago, President Lyndon Johnson vastly escalated the war in Vietnam. The process had started in August 1964, when LBJ convinced Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a measure that granted the president sweeping authority to use military force in the area. Johnson said that the authority from the resolution was so broad it was like “grandma’s nightshirt” since “it covers everything.” Nonetheless, he promised Arkansas Sen. J. William Fulbright, who led the resolution through the Senate, that he would return to Congress if he wanted to use significant force in the future.

The following year, after his massive landslide victory against Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater, which produced huge liberal Democratic majorities (295 Democrats in the House and 68 in the Senate), LBJ continued moving the escalation forward, first with a fierce bombing campaign, known as Operation Rolling Thunder, against the communist forces, and then by sending tens of thousands of ground troops into the conflict

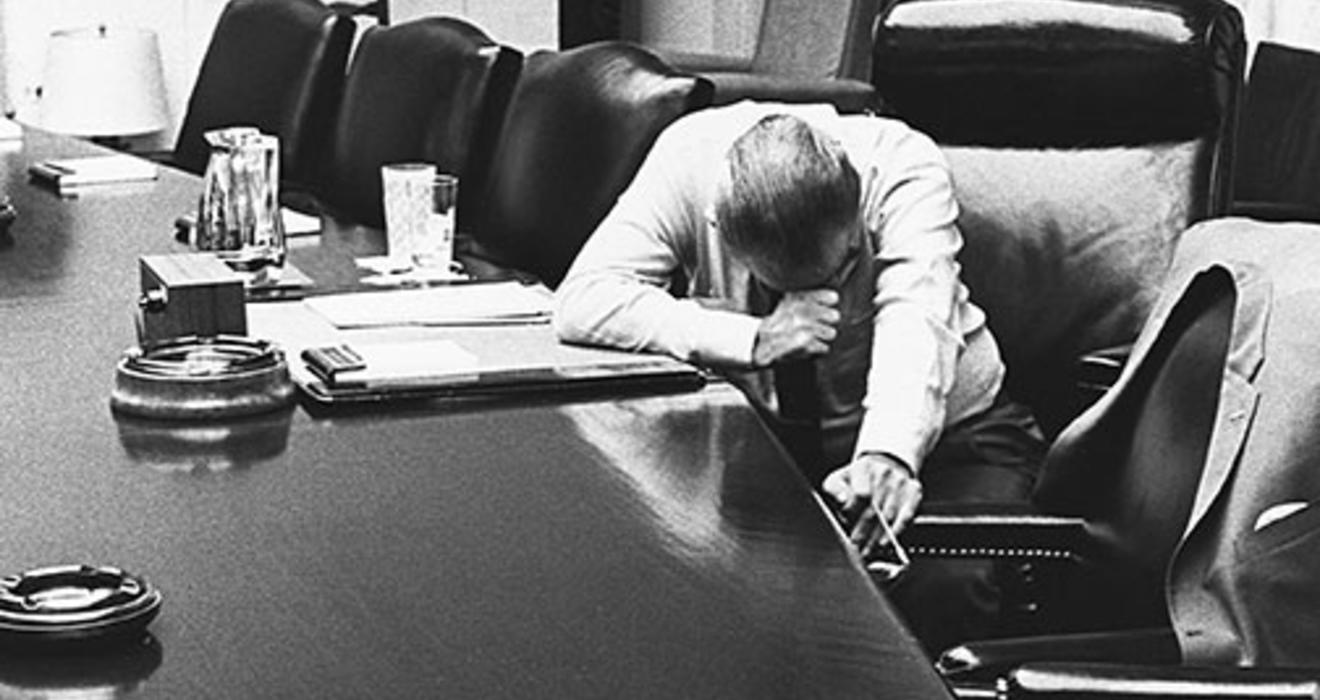

The war turned into a huge disaster for Johnson, for the nation, and for the Vietnamese. “That bitch of a war,” Johnson later said, “killed the lady I really loved — the Great Society.” What started small would grow rapidly into a huge and deadly ground war that lasted until 1973. In the end, the U.S. government withdrew its forces, and South Vietnam fell to communism. The war resulted in massive casualties and permanently undermined confidence, within the United States and throughout the world, in America’s stated objectives in its fight against communism.

Vietnam remains a major topic in our classrooms. Undergraduates continue to learn a number of important lessons from examining America’s war in Vietnam and its aftermath. The war that unfolded in Southeast Asia (though it was never officially a war) is an integral part of classroom conversations about U.S. history and international relations.

One of the most important discoveries I hope students take away from a deep dive into the history of the Vietnam War is an understanding of the dangers we face when our elected officials allow for a blind adherence to foreign-policy orthodoxies to dictate their decisions and when political considerations guide what happens with regards to war and peace.

Both factors were clearly at work when Johnson kept making the decision to increase U.S. involvement rather than to withdraw. Johnson came from a generation of Democrats who believed that for strategic and political reasons, it was essential to remain tough against communism everywhere in the world. He subscribed to “the domino theory,” meaning that if one country fell to communism, no matter how small or seemingly irrelevant, others quickly would follow. This was the argument being put forth by many of his top national-security advisers. Even as a number of legislators privately expressed doubts about the wisdom of this strategy, Johnson stood firm.

Johnson’s decisions also were shaped by his political fears that for a liberal Democrat to succeed on domestic policy, he had to be hawkish on foreign policy. The president remembered the 1952 elections, when Republicans used the issues of the fall of China to communism, the efforts to root out communism within the United States, and the stalemate in Korea to take control of the White House and Congress. Johnson believed that what he called the “great beast” of the right was the real danger facing Democrats, and he never wanted to be outflanked by conservatives again. Adviser Jack Valenti later recalled that Johnson felt the “Democratic right and the Republicans” would have “torn him to pieces” for losing in Vietnam. Johnson pushed back against every proposal for withdrawal by reminding advisers and colleagues of how this would undermine his domestic agenda.

There are many moments in the story where my students see just how far individuals would go in allowing for politics to enter into their decisions. Politics doesn’t really stop at the water’s edge, and sometimes the mix between the two got very ugly in the 1960s.

Perhaps the most shocking example of the connection between politics and foreign policy during Vietnam took place in the heat of the 1968 presidential campaign between Vice President Hubert Humphrey (Johnson had announced in March that he would not run for re-election) and former Vice President Richard Nixon. There is now strong evidence showing that people working for Nixon’s campaign sent signals, through the Republican activist Anna Chennault, to the South Vietnamese that the terms of a negotiated settlement would be better if Nixon won. Soon after Johnson had announced that there was to be a halt in the bombing, the Nixon people urged the South Vietnamese to hold off on agreeing to any deal, thereby extending the war.

After learning of these signals through FBI surveillance, Johnson told Sen. Minority Leader Everett Dirksen (known as the “Wizard of Ooze” for his long-winded and overly dramatic speeches) about what he had heard from the wiretaps. “I think that we’re skirting on dangerous ground,” Johnson told his old Senate colleague. “They oughtn’t to be doing this,” he said in frustration. “This is treason.” Johnson said he didn’t know exactly who was running the operation, but that “I know this: that they’re contacting a foreign power in the middle of a war.” Dirksen responded, “That’s a mistake!” Johnson said: “And it’s a damn bad mistake.” In the end, Johnson didn’t make this public, fearing the impact of revelations that he was spying on the Republican Party and that the information could cause great instability if Nixon won.

The connections between politics and foreign policy continue to this day. During his presidency, President Barack Obama has had trouble moving forward with a number of issues, such as closing Guantánamo, as he has faced fierce political pushback from Republicans and Democrats scared of being tagged as soft on terrorism. The president has had to navigate the threat of ISIS in a toxic political environment where Republicans continually charge that the administration is not doing enough to combat the threat.

Johnson did not take his critics very seriously, an important reminder that presidents must avoid creating an echo chamber in the Oval Office where opponents’ voices are not heard. Johnson dismissed the early college protests in 1965, saying that the threat was from the reactionary right. From a very early stage, Johnson heard doubts about the wisdom of the war and its necessity, even from conservative hawks like Georgia Sen. Richard Russell. When Russell expressed his views in May 1964 during a telephone conversation, Johnson didn’t disagree — but he didn’t expend much energy trying to find a way out of the situation. Russell warned: “It’s the damn worse mess that I ever saw. ... I don’t see how we’re ever going to get out of it without fighting a major war with the Chinese and all of them down there in those rice paddies and jungles.” Johnson’s overriding instinct was still to keep getting the nation deeper and deeper into the conflict.

After the 1964 Democratic landslide, Humphrey wrote Johnson an impassioned memorandum urging Johnson to get out of the war. He warned that the war would end up destroying the president’s domestic agenda. “Politically, it is always hard to cut losses,” Humphrey wrote. “But the Johnson administration is in a stronger position to do so than any administration in this century. Nineteen sixty-five is the year of minimum political risk for the Johnson Administration. Indeed, it is the first year when we can face the Vietnam problem without being preoccupied with the political repercussions from the Republican right.”

Johnson’s response was to kick Humphrey out of his inner circle of advisers. As the protests escalated on the college campuses and on the streets, Johnson became even more hardened, angry with the protesters and frustrated that they didn’t appreciate what he was doing. He came to perceive the anti-war movement as a movement of dangerous opponents, rather than voices that might guide him toward a better policy. He believed that the movement was undercutting his efforts to win the war and bring it to an end. Johnson told reporter Hugh Sidey, “I am worried about attempts to subvert the country. I am not a McCarthy [a reference to red-baiting Wisconsin Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who led the anti-communist crusade in the early 1950s], but I am concerned.” When Martin Luther King Jr. publicly turned against the war in April 1967, Johnson — who had worked closely with civil-rights leaders on some of the most important legislation of the day — was furious, and came to see King as an opponent rather than an ally.

The long-term impact of a failed war was devastating on multiple fronts — another lesson students glean from studying Vietnam and its aftermath. It would take decades to start getting over the war.

The quagmire of Vietnam undercut the ability of the United States to mount large-scale ground wars in the future. In 1973 Congress dismantled the peacetime draft, which had been in place since World War II, replacing the system with a professional military. This made it harder for any president to mobilize the number of forces that had been used in World War II and in Vietnam.

The war also had deeply undermined public confidence in what elected officials and military leaders said about military conflict — and about everything else. Polls show that it was in this period, before Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal, that confidence in government started to decline. Too often during the 1960s the American people had heard lies, where public statements totally contradicted what was happening on the ground. The ability of the communist forces to mount the Tet Offensive in January 1968 was a devastating blow to Americans’ belief in public statements that victory was around the corner. CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite, known as “the most trusted man in America,” jettisoned the norm of objectivity when he went on the air and said the war could not be won. “To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To say that we are mired in stalemate,” Cronkite continued, “seems the only realistic, if unsatisfactory conclusion.” Upon seeing the broadcast, Johnson reportedly said: “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the country.”

Each time subsequent presidents tried to rally the nation behind a cause, there would be much more resistance to large-scale intervention. Public opinion tended to oppose the use of ground troops. The horrific attacks of 9/11 did significantly boost support for a military response, and skepticism from the Vietnam era seemed to be on hold as President George W. Bush put forward claims about Iraq’s possession of weapons of mass destruction. But even then, neither the Bush administration nor Congress believed there would be support for anything like reinstating the draft or launching a ground war on the scale and scope of Vietnam.

Today, 50 years since the acceleration of the war began, Vietnam remains a big topic in our discussions of modern American history. The war deeply impacted the 1960s and the decades that followed. It devastated the legacy of a president who had undertaken transformative policies on the homefront and permanently shaped the ways in which our nation thinks about decisions about war and peace. Yet not all of its legacy is bad. Many students walk away from these discussions with a willingness to have honest and open debates about the way in which we have handled international relations.

In many ways, the war in Vietnam never ended.

A War Still With Them

The war in Vietnam ended three decades ago, but for many of those who fought it – or chose not to – it’s never really over.

Student Dispatch: Drawing on Stories of the Vietnam War For a Message That Speaks to Today

5 Responses

Thomas F. Schiavoni ’72

10 Years AgoCollapse of an Old Order

The April 1 PAW issue tripped an emotional toggle switch. Recollections from sophomore year tumbled off the conveyor belt from my cargo hold of memories of campus protests and a nationwide student strike in the spring of 1970. A blurb about an upcoming student referendum on bicker seemed trivial in contrast to the seriousness of the feature “A War’s Legacy” and references in the editor’s letter and Class Notes to alumni casualties and protesters along Nassau Street during the Vietnam War era. Still, the passing mention of bicker reminded me of something from that time.

Classes, exam schedules, and social activities were thrown into confusion. An emergency meeting was convened at a Prospect Avenue club where I had successfully bickered. In deadly earnest, a soul-searching discussion ensued on how best we should respond to the strike. A debate arose about canceling Houseparties. One proposal was seriously advanced that the planned formal could dispense with black ties and tuxes in solidarity with the strikers. It was at that point that I remembered the Selective Service card in my wallet and the real possibility of being drafted in a misbegotten conflict in which 1.5 million Vietnamese and 58,000 Americans eventually perished.

I never set foot in that club again — not out of disrespect for its members, but because life on the Street suddenly seemed irrelevant. An old order was collapsing around us. And there were far more important matters to face as I came of age in that season long ago.

William Watson ’65

10 Years AgoThe Legacy of Vietnam

I cannot compose a compact response to Professor Zelizer’s article about the Vietnam War. The closest I can come is to say that for me, and at least some of the men who died by my side, our fight was more than just an impediment to “moving forward” on an expanded welfare state.

Alfred Muller ’62

10 Years AgoThe Legacy of Vietnam

As a physician who served in Vietnam (1970–71), I read with great interest the fine article by Julian Zelizer and would like to add an interesting historical footnote. Some time after his retirement as President Johnson’s secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, I was privileged to meet Wilbur Cohen, once dubbed “the man who built Medicare.” I asked him whether we would ever get universal health care in the United States, to which he replied that he and the president had just such a comprehensive plan waiting to be introduced. Medicare was only the first step.

After a few years they hoped to introduce the second phase, which they even had named “Pedicare,” for those up to the age of 21. The third phase would be a gradual one, over the course of a few years. Congress would slowly lower the age for Medicare eligibility and raise the age for Pedicare eligibility until everyone was covered. I asked why the complete plan never had been implemented, and he replied with one word: “Vietnam.” There was simply no money or political capital left for this important social program. And so Vietnam had claimed another victim, universal health care for all Americans, which we still have not attained almost 50 years later.

Benjamin A.G. Fuller ’67

10 Years AgoThe Legacy of Vietnam

Professor Julian Zelizer noted that “the quagmire of Vietnam undercut the ability of the United States to mount large-scale ground wars in the future” (feature, April 1) because of the dismantling of the draft.

The unintended consequence has been the ability of this country to wage wars for a very long time, since the vast majority of Americans have no connection to the military, approve of their elected officials pushing the costs down to future generations, and certainly would not join themselves, as Boston University’s Professor Andrew Bacevich *82 and others have shown. The benefit of the draft was that policymakers had to make it clear to the American people that going to war was of direct national interest. For World War II and Korea they did; for Vietnam they didn’t. With the draft, most Americans had “skin in the game.” One hopes that Professor Zelizer points this out to his students, who are unlikely to have any direct contact with those who do the fighting.

Brig. Gen. Creighton W. Abrams Jr. ’62

10 Years AgoThe Legacy of Vietnam

It takes a healthy dose of chutzpah to say that “in many ways, the war in Vietnam never ended,” a statement I think is born of Professor Zelizer’s desire to ensure that LBJ’s role in the war and his commentary on it will never end.

My chief complaint is about the notion that, because of LBJ’s presumed failures as a wartime president, no president since then has had the leeway to commit major forces into combat quickly and, one would hope, decisively.

First of all, how can that be a bad thing? Big wars are pretty serious business and worthy of the undivided attention of the American people, of their elected representatives, and of their resolve. Getting into a big war should be hard, not easy. And the War Powers Act has not, I believe, affected our presidents’ freedom of action in smaller actions like Grenada, Panama, Afghanistan (October 2001), etc.

Secondly, I believe there has not been any requirement for a major commitment of combat forces since Vietnam. But there was a pretty darn big commitment — with congressional approval — when the Army sent over half of its active divisions in the 1990–91 Gulf War, to say nothing of tons of field artillery units, etc. Those seven divisions were more than we sent to Korea and about what we sent to Vietnam.

LBJ is worth studying, but I don’t think we need to exaggerate his importance in American history. He was an imperfect wartime president, and that can be said of almost every wartime president we have had.