As We Celebrate Nurses, Paul Stepansky ’73 Commemorates Their Forebears

The book: In the international battle against coronavirus, medical workers sit on the front lines and the front pages. Thousands have come out of retirement to support understaffed hospitals or distanced themselves from loved ones to stop the spread. Some of them have shared viral selfies wearing PPE and holding signs that say “I stayed at to work for you. Please stay home for us.” These acts of heroism have echoes of previous generations.

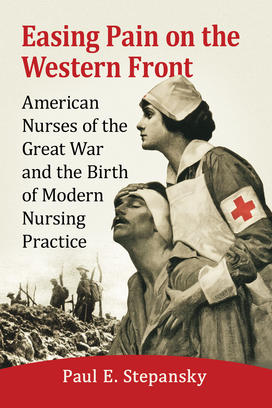

In his new book, medical historian Paul Stepansky ’73 praises the nurses of World War I. Easing Pain on the Western Front (McFarland) describes civilian nurses treating “shell shock,” the unprecedented injuries of mechanized warfare, and a global epidemic of Spanish Flu. Stepansky compares the medical procedures on the Western Front with those of earlier wars, giving special attention to new technologies that became essential for modern nursing.

The author: Paul Stepansky ’73 is a medical historian and interdisciplinary research associate at Weill Cornell Medical College. After studying history at Princeton, he earned his Ph.D. at Yale and became the managing director of The Analytic Press, an imprint that produces mental-health books and journals. After writing and editing several books about psychoanalysis, he became a full-time author in 2006.

Opening lines: It was the all-too-common story of the World War I nurses, the narrative thread that linked the vagaries of their wartime experiences. The war was to be the adventure of a lifetime. The opportunity to serve on the Western front was not to be missed, not by hospital-trained nurses and not by the equally well-trained volunteer Red Cross nurses. For both groups, the call to duty was suffused with the excitement of a grand adventure.

Beginning in the spring of 1917, the war abroad was the event of the season, and trained nurses and untrained volunteers rushed to the welcoming embrace of the American Red Cross and the fledgling Army Nurse Corps. Julia Stimson, a Vassar graduate who led the St. Louis base hospital unit to Europe in May 1917, was overwhelmed with the honor it bestowed on her and the opportunities it promised. “To be in the front ranks in this most dramatic event that ever was staged,” she wrote to her mother, was “all too much good fortune for any one person like me.” Helen Fairchild, an Army reserve nurse whose Pennsylvania Hospital Red Cross unit shared space on the SS St. Paul with Julia Stinson’s St. Louis contingent, wrote her brother and mother in transit: “Our two groups of nurses, the one from St. Louis under Miss Julia C. Stimson and our group from Philadelphia are really excited to be part of this great adventure.”

Nurse Fairchild’s only problem was seasickness occasioned by a “rocking and rolling” ocean, but no amount of nausea could dampen the sheer exhilaration of the whole thing. A few days later, she wrote her mother of the nurses’ memorable send-off at Philadelphia harbor:

I must say, it was pretty exciting down at the docks when we left on Saturday. All sizes of boats in the harbor tooted and blew their whistles at us, and people on ferry boats waved and cheered. I know you couldn’t be there to see us off and I was thinking of you, but my mind was distracted. How strange everything seemed, but oh how exciting!

The fanfare was worlds removed from Fairchild’s forebears, the women hospital workers of the American Civil War. They made their own travel plans and journeyed to hospitals at their own expense, often with the disapproval of friends, family, and society at large. In mid-nineteenth-century America, after all, hospitals of any sort remained charitable institutions tainted, the historian Jane Schultz remarks, by “an aura of stigma of sexual impropriety.” But this bit of recent history was long forgotten in the mania of 1917. On the deck of the St. Paul, Julia Stimson did nothing to calm down the nurses in her charge. Rather, she whipped them up further. Borrowing language from a letter to her mother, she sounds more like a stellar athlete chosen to represent her nation in the Olympic Games than a nursing administrator headed for the Western front. For Stimson,

to be in the front ranks in this most dramatic even that ever was staged, and to be in the first group of women ever called out for duty with the United States Army, and in the first part of an army ever sent on an expeditionary affair of this sort, is all too much good fortune for any persons like me.

The American nurses who followed Stimson, Fairchild, and others in the fall of 1917 and spring of 1918 were no less welcoming of adventure abroad than the first wave of the preceding summer. Absent any understanding of what lay before them, gaiety abounded, and the trip over could take on the ambience of a holiday cruise. …

Reviews: “Easing Pain on the Western Front provides an important contribution to scholarship on nurses and war. Moving beyond exploration of why nurses might serve in the military during wartime, Stepansky provides an historically informed examination of nurses’ actual wartime practices. In the case of World War I, these practices changed the experience of wounded soldiers, in no small measure through nurses’ skilled use of the cutting-edge technologies of the time —technologies that contributed to the transformation of American nursing in the decades following the Great War.” – Patricia D’Antonio, Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing, University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing

No responses yet