Welcome to Whitman College

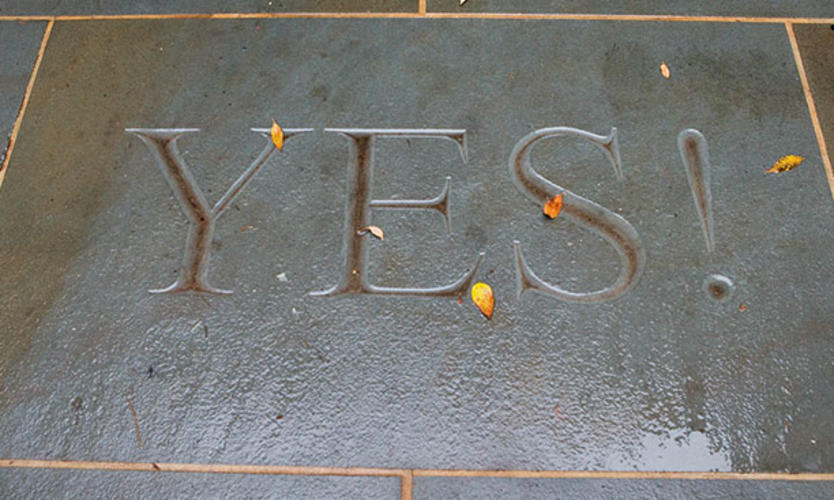

The formal gateway to Whitman College, Princeton’s new residential college, lies immediately across from the Dinky station. Students can disembark from the train, cross a bridge over a small, dry moat, and pass through the arch at Hargadon Hall. Just before stepping through the arch, they need only look down to recall the day that their Princeton experience began — and the sense of potential that came with it. “Yes!” the stone shouts, just as former admission dean Fred Hargadon alerted fortunate applicants of their success.

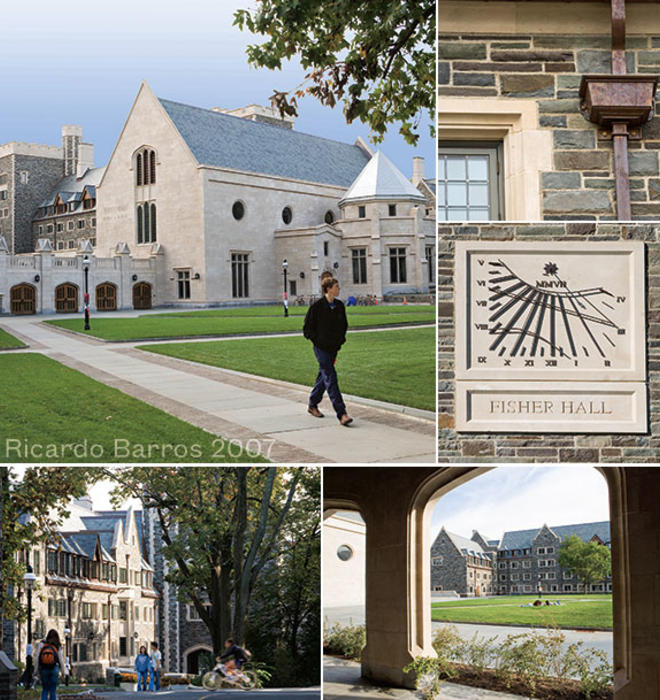

The entry was meant to recall the gateway to campus of the early 20th century, when the train deposited students and visitors at Blair Hall, explains architect Demetri Porphyrios *80. In his design of the college, Porphyrios kept one eye on history and the other on the “humanist” experience of today’s Princeton. The Whitman campus unfolds on different levels, with each structure taking an individual identity while contributing to “a community of buildings, like a family,” he says. Moldings may look the same from a distance, but look more closely, and you see that they are different — “like people’s faces.”Since September, about 500 students have called Whitman College home, living in some of the most-desired suites on campus. Students stream into Whitman’s innovative dining hall and meet for seminars in rooms that mix the convenience of the new with the old-style warmth of fireplaces and oak paneling. Porphyrios says he designed the spaces, indoors and out, to encourage conversation and casual encounters.

The eastern side of the college takes in Mazo Green, an expansive lawn that links Whitman to the larger University. It’s a majestic view — and a symbolic one, says its architect. “It’s a very important vista,” Porphyrios explains. “With open arms, it says: I am Whitman. Please come in. The gates are open.”

Clockwise from top left above: A student walks out of Whitman on Mazo Green, with Community Hall in the background; Handmade copper gutter; The sundial on the wall of Fisher Hall; A view through Wright Cloister of the Class of 1963 Courtyard toward 1981 Hall, left, and South Baker Hall; and nearing the college gateway on Pyne Drive with a view of North Hall, the Murley-Pivirotto Family Tower, and Hargadon Hall.

Materials were chosen to last 200 years, and 77 masons cut and selected each piece of stone to special parameters in building the walls. “When you come to the things that envelop the wall of a building, the texture and the tactility of the materials are extremely important,” Porphyrios says. “I wanted it to be a group of buildings that will weather naturally, age gracefully, have the wrinkles of time.”

Students relax in a 1981 Hall common room, top, and study in the North Hall library, with its custom-designed light fixtures and paneled walls.

Top left, the 220-student-capacity main dining hall, with 35-foot ceilings, circular windows, vaulted ceiling, and bluestone floors. Top right, Professor Paul Sigmund with Efe Balikcioglu ’10 after a seminar in an adjacent, octagonal room. Above, the servery, which has become a draw to students from across campus. At left, the ceiling and chandelier in the small octagonal meeting space, and the building’s name engraved — an example of the modest ornamentation throughout the college.Some observers have remarked on the college’s lack of decoration; Porphyrios says he intentionally allowed empty space for residents to add ornamentation over time, allowing the college to grow naturally.

Top, Robert “Bud” Grote ’08 enjoys what many believe to be the best digs on campus, shared with one roommate. Below, students rehearse in Whitman’s 65-seat theater.

Clockwise from top left, Master of the College Harvey Rosen sits in Wright Cloister, named for former Princeton vice president and secretary Thomas H. Wright ’62, with Lauritzen Hall out to the left. Graduate student Luke Uribarri shows off his single room. Students walk through the arch at Hargadon Hall. Chester Courtyard, which was inspired by Porphyrios’ experience in Princeton’s Graduate College; Fisher Hall, right, and North Hall are in the background.Porphyrios points out that though the buildings evoke the great universities that emerged in the Middle Ages in Europe, the grounds were designed in the character of an American college campus. Those older European universities, such as Oxford and Cambridge, have straight paths and manicured greens upon which only senior scholars may tread. By contrast, Whitman’s campus has trees, zig-zagging paths, and different levels that invite people to gather. “Here, nature and manmade buildings mix together,” Porphyrios says.

No responses yet