Late in World War II, the Allies prepared for their bloody invasion of Fortress Europe. Many observers expected to see heartrending destruction of art and architectural treasures as bombs rained from the sky and soldiers ransacked and looted. Culture had suffered grievously in countless wars of the past; why should this, the most horrific conflict in all human history, be any different?

But it was different: The Allies took remarkable measures to protect threatened art. “Shortly we will be fighting our way across the continent of Europe in battles designed to preserve our civilization,” Gen. Dwight Eisenhower told his commanders just before D-Day in a historic message signaling an enlightened new attitude. “Inevitably, in the path of our advance will be found historical monuments and cultural centers which symbolize to the world all that we are fighting to preserve” — and so he ordered his commanders to safeguard those treasures as their armies swept violently forward. It was a first in military history.

Above, “Monuments Men” examine relics of the Holy Roman regalia upon their return to Vienna in 1946. Lt. Ernest DeWald *14 *16 is at far right, and Lt. Perry Cott ’29 *37 is third from left.

Key to this noble effort were art historians serving in the ranks of the American, British, and Canadian forces, including more than a dozen young Princetonians. As described in a new book by Robert Edsel, a former Texas oilman who recently set up the Monuments Men Foundation to honor their memory, and co-author Bret Witter, these soldiers volunteered for the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Service (MFAA). They tagged along with the advancing troops, warning them of art landmarks to avoid and performing emergency restorations as needed to paintings, sculpture, and architecture. After the Third Reich collapsed, MFAA officers undertook the daunting task of finding lost art, which the enemy had scattered for safekeeping across more than a thousand secret locations in Germany alone — including deep underground in salt mines. Assembling this jumbled material at “collecting points,” they began the tedious process of repatriating 5 million objects, a herculean task that took until 1951 to complete.

Edsel calls their efforts “a completely overlooked part of history,” so little public attention have they received. But 60 years later, the records MFAA kept are still used regularly by museum professionals like Nancy Yeide of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., who researches the ownership history of paintings — their “provenance.” The contribution of MFAA was, she says, “absolutely inestimable. It should be a source of pride to Americans. Especially when you consider there were a lot of things the U.S. military had on its plate, like feeding and clothing Europe.”

It seems especially admirable when compared to the actions of the Soviet Union, which dispatched a Trophy Commission in 1945 to steal 2.5 million art objects in reparation against Germany, including the famous gold artifacts excavated by Schliemann at Troy (which didn’t surface again until the 1990s). Berlin’s Museum Island was systematically ransacked. Russia still refuses to return many of these looted items. By contrast, the 350 or so members of MFAA were selfless and disinterested in their efforts to return art to its proper owners, including those in the former Reich — even though the U.S. government didn’t always follow MFAA’s lead.

Princetonians figured prominently in MFAA. The University’s Department of Art and Archaeology was nearly 60 years old when the war began and was rivaled only by Harvard’s as the finest in the nation. Many professionals had trained in McCormick Hall and the Art Museum, including the innovative director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Alfred Barr ’22. He became the first American to warn of the threat to art by Nazi “sons-of-bitches,” as he called them after witnessing a Stuttgart rally in 1933 — the Nazis routinely burned paintings they considered “degenerate” and looted Europe’s treasures for their personal aggrandizement. Hitler, a frustrated artist himself, planned a megalomaniacal museum for Linz, Austria. In assembling his trove, the Führer competed against Washington’s National Gallery of Art (opened in 1941) and other world museums — but he had persuasive powers of acquisition they lacked. At his death he owned an astonishing 8,000 paintings, double the number the National Gallery has been able to amass over the past 70 years.

When the war ended, MFAA established a collecting point in bomb-cratered Wiesbaden, Germany, in a building that had served as a state museum before the war and later housed Luftwaffe headquarters. Conditions were grim in the building, where every window was shattered and doors had been blown off their hinges. A ring of U.S. Army tanks kept looters away. As crates arrived daily in trucks, Capt. Patrick “Joe” Kelleher *47 and fellow officers were staggered to find that they contained some of the greatest masterpieces in art history, including Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. For Kelleher, it was like returning to the McCormick Hall classroom where he had studied these very works as a master’s-degree student just before enlisting.

Nestled in one box was a glittering treasure: St. Stephen’s Crown, a talisman held sacred by the Hungarian people for 700 years. Kelleher seized the opportunity to study the seldom-seen crown up close, and later he wrote his Princeton dissertation on it. The U.S. government refused to send the crown back to Communist Hungary, so it languished at Fort Knox until being repatriated in 1978 — after Kelleher, by then retired as director of the Princeton University Art Museum, had been invited to examine it one more time.

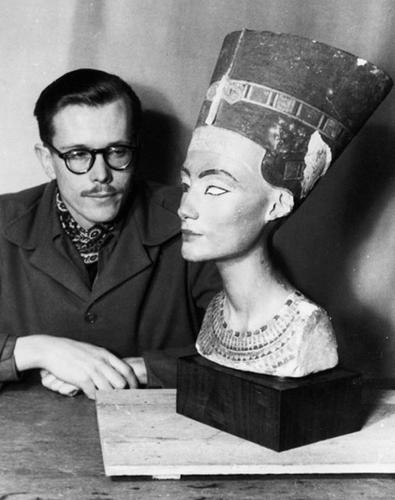

Boyish and high-spirited, Kelleher liked to needle Capt. Walter Farmer, the brusque and jumpy director of the Wiesbaden collecting point. At Christmas 1945, Farmer went out of town, leaving strict orders that no more crates should be opened — the German museum curators had packed the artworks carefully before hiding them in the salt mines, and Farmer wanted them to remain undamaged. But Kelleher invited fellow art lovers for a bibulous dinner party and, with great fanfare, pried open a lid to extract the most famous of all Egyptian sculptures, the bust of Nefertiti. Delighted to find her unbroken, they raised their glasses to a woman whose beauty was undimmed after 3,300 years.

When Farmer found out, he fulminated about this “outrageous act of disobedience by a fellow officer.” He knew that the ravishing Nefertiti was dogged by controversy already: She had been whisked to Berlin within months of her discovery by archaeologists in 1912, and now the Egyptian government was clamoring for her return. Nefertiti remains a sore point even today: Over strident objections from Cairo, the bust has just become the centerpiece of Berlin’s Neues Museum, gutted by bombs during World War II and not reopened until last year.

Given MFAA’s mission to return all artwork to its rightful owners, Farmer was incensed when top generals ordered him to pack up 202 of the very best paintings for shipment to the National Gallery of Art for safekeeping, including 15 Rembrandts. Would they ever be returned to the German museums that formerly housed them? he wondered. Kelleher and other MFAA officers grimly assembled “The 202” for shipment, but not before 32 of them signed the “Wiesbaden Manifesto” on Farmer’s desk Nov. 7, 1945. This letter of complaint to the military higher-ups warned that the German people would see this as “a prize of war” confiscation: No other act “will rankle so long, or be the cause of so much justified bitterness.”

Author of the Wiesbaden Manifesto was feisty Capt. Everett “Bill” Lesley *37, later an art history professor at Old Dominion University. A seasoned MFAA veteran, he had followed the advancing armies after the Normandy invasion and reported on the condition of art-rich places along the way: Chartres was mercifully intact, he found, but La Gleize Cathedral in Belgium had been pulverized. Other Princeton signers of the manifesto included Kelleher, Lt. Charles Parkhurst *41, and 1st Lt. Robert Koch *54, the last familiar to many alumni from his long career teaching art history at Princeton. “We believed first of all that the language was the same the Nazis had used when they looted, which was ‘protective custody,’” Parkhurst later said in explaining why he signed the manifesto. “We thought that was a bad omen.”

Art historians in the United States were unhappy about “The 202” confiscation as well. Truman’s secretary of state received a stern letter from Rensselaer Lee ’20 *26 on behalf of the College Art Association, a professional organization representing artists and academics. Lee had advised President Franklin Roosevelt on cultural treasures in the theater of war and later became an esteemed professor at Princeton. But despite all objections, “The 202” were delivered to America as ordered, where nearly a million visitors saw them on display at the National Gallery in the first “blockbuster” show in history, military police sternly standing guard. Lee and others were gratified when all the paintings finally were returned to Germany in 1948, a positive outcome that the Wiesbaden Manifesto perhaps helped ensure.

Among the young curators at the National Gallery of Art was serious-minded Craig Hugh Smyth ’38 *56, who supervised the wartime removal of that museum’s contents to Biltmore Estate in Asheville, N.C. As a naval lieutenant, he went on to establish an MFAA collecting point in Munich just a month after the city fell to the Allies, housing it in former Nazi administration buildings still draped in green fishnet camouflage. (Nearby museums had been destroyed by bombing.) Smyth held conferences in the room where hapless Neville Chamberlain had signed the Munich Accord that promised “peace for our time.” He found framed portraits of Hitler heaped in the basement, along with booby-trap explosives that blew one workman to bits.

Trucks constantly rumbled across the courtyard, bringing art found deep in Austrian salt mines. Smyth was joyous at the arrival of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine” and Jan van Eyck’s “Ghent Altarpiece,” among thousands of works the Nazis had intended to destroy to prevent their capture by the Allies at war’s end — but time suddenly ran out. Not every shipment was greeted with delight, however. One day a box arrived filled with gold teeth and children’s orthodontic braces, discovered at Dachau.

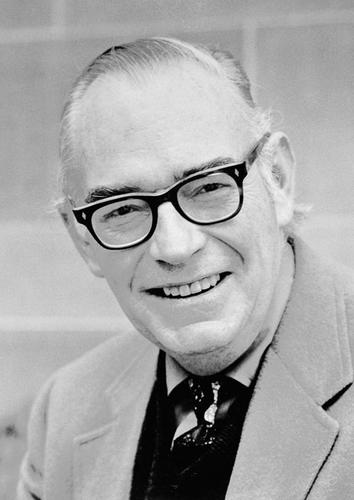

Recent years have brought heightened interest in the problem of looted art from the Holocaust era. Major museums, including Princeton’s, have reinvestigated their collections to be certain they do not contain stolen works. To assist in this global effort, the National Gallery’s Yeide has assembled a catalog of the collection of top Nazi Hermann Goering. His nefarious trove included 2,000 paintings, Yeide has proven — not 1,300 as previously thought. She could not have completed her work without the diligent records of Smyth and his Munich collecting point. “They did a fantastic job, a monumental job,” she says, “especially if you think about the situation they were dealing with” amid the devastation of a bombed-out city. Smyth’s distinguished career was only beginning: In later years he served as director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University.

MFAA in Italy was headed by another Tiger, Lt. Col. Ernest DeWald *14 *16. Genteel and effortlessly polylingual, he had attended Rutgers before coming to Princeton for his Ph.D. After service in World War I he considered a career as a singer, but Dean Andrew Fleming West 1874 convinced him to enter academia instead, so he joined the Department of Art and Archaeology in 1925. Starting in 1943, he worked with MFAA in North Africa, identifying what ought to be preserved in the coming invasion of Italy. Then he moved north with the conquering armies through Sicily and the Italian mainland, overseeing emergency repairs to damaged buildings and finding museum art hidden in the countryside. Ready with expert assistance was his Princeton departmental colleague Charles Rufus Morey, founder of the Princeton-based Index of Christian Art (now the world’s largest archive of medieval art), who was serving as a cultural attaché in Rome.

DeWald’s pocket diary, little-noticed today in Firestone Library, records the excitement and danger of these tumultuous times. Air-raid sirens howled as he reconnoitered medieval towns for endangered art. DeWald often came upon Army engineering units bulldozing fallen buildings out of roadways, using the debris to patch holes in blown-up bridges — until he frantically waved them to stop, pointing out fragments of historic sculpture, fresco, and manuscripts mingled with the rubble. “It’s amazing what Italian experts can piece together from what appears to be just a pile of smashed rock,” he told PAW in a wartime letter.

DeWald decried needless Allied bombing, including an attack on the ruins of Pompeii. But American transgressions paled beside the destructiveness of the Wehrmacht, he repeatedly said. He was horrified by their dynamiting of venerable campanile towers and thousands of bridges, all across Italy. As curators watched helplessly, they had poured benzene and sulfur on the historic state archives of Naples and lit a match. He blamed them too for the burning of the huge Roman ships recently excavated from the bed of Lake Nemi, south of Rome. Of these priceless nautical remains that Mussolini had drained the lake in order to salvage, nothing was left now but heaps of blackened nails. The Germans also had wreaked havoc on the elegant Palazzo Ruspoli nearby, where, DeWald told his diary, “every stick of furniture remaining was hacked to pieces and the pictures slashed to ribbons.”

DeWald was proud of his record in tracking down lost art, including Titian’s “Danae” and Pieter Bruegel’s “Blind Leading the Blind,” both filched from storage at Monte Cassino abbey (later pounded to dust by American bombs) as gifts for Goering and eventually found in the bowels of the Austrian salt mines. To forestall looting and vandalism by Allied troops, DeWald wrote the Soldier’s Guide to Rome, which fresh-faced GIs carried through the Forum as they gawked at historic ruins. Subsequently, he was transferred to Austria, where he helped sort out Hitler’s artwork, working with yet another Princeton-trained expert — S. Lane Faison *32 of the OSS Art Looting Investigation Unit. Later a legendary professor at Williams, the pistol-carrying Faison interrogated shady dealers who had rounded up art for the Führer. Some swallowed cyanide rather than be questioned by this mild-mannered academic.

Back at his desk in McCormick Hall, DeWald wrote the introduction for the 1946 book Lost Treasures of Europe, a photographic catalog of the continent-wide destruction wrought by six years of pillaging and bombs. “The loss or destruction of these prized heritages of the past becomes in fact a personal loss comparable to that of a friend,” he said mournfully. Appointed as director of the Princeton University Art Museum in 1947, he bought an ancient sculpture of a goat’s head — “Princeton Billy,” the students called it — that turned out, ironically, to have been snitched from a collection in Rome during the war. DeWald promptly returned it, though Italy soon gave it to Princeton as a gesture of friendship.

In 1950, the Austrian government honored his personal contributions to MFAA in their country by briefly exhibiting Vermeer’s “The Art of Painting” at the Art Museum. Perhaps the greatest of the 34 works surviving by that legendary Dutch artist, it had been purchased by Hitler himself with proceeds from Mein Kampf. Rescued by American troops from the salt mines at Altaussee, Austria, it ultimately was repatriated to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna — not to the aristocrat who had sold it to Hitler, Jaromir Czernin, who complained bitterly. Today, Czernin’s descendants are demanding to have the painting back, saying that he only parted with it under threat. The Austrian government hopes to avoid giving up its beloved Vermeer, which may now be worth a quarter-billion dollars. It is still smarting from the loss of five Gustav Klimt paintings in 2006: Stolen by the Nazis from a Jewish family and displayed in a Vienna museum for decades, they finally were repatriated by court order to a California woman after lawyer E. Randol Schoenberg ’88 successfully pleaded her case.

Many MFAA men — Princetonians and others — later became museum directors, including Charles Parkhurst, who headed the Baltimore Museum of Art. Joe Kelleher replaced DeWald as director of the Princeton Art Museum (his esteemed predecessor later dropped dead from a heart attack in Palmer Stadium parking lot at the 1968 Columbia game). Working with Barr and other experts, Kelleher selected the artists for the Putnam Collection of modernist sculpture scattered across campus and wrote the guidebook Living With Modern Sculpture.

Today, the World War II generation is fast exiting the scene, with nearly 6,000 U.S. veterans dying every week. The loss of Faison and Smyth in 2006 and Parkhurst in 2008 leaves just one living Princeton MFAA man, Robert Koch, now 90 and unable to be interviewed because of failing health. Many Tigers fondly recall Koch’s courses on Northern Renaissance art, which he taught for 42 years. Koch grew up in academe as the son of drama professor Frederick Koch of the University of North Carolina, whose Carolina Playmakers pioneered the American “folk play” and whose star student was Thomas Wolfe. The younger Koch earned a master’s degree at the University of North Carolina before enlisting in 1942. Years later in conversations with undergraduates, he sometimes mentioned, in his modest Southern way, his MFAA service and how those unspeakable Nazis had intended to blow up the salt mines, incinerating the “Ghent Altarpiece” and so much else.

But now, two decades after he retired, his stories largely have been forgotten. Current Princeton faculty recall almost nothing about his wartime service — “I didn’t really know Bob Koch and certainly never heard him mention that subject,” says one professor who passed him in the hall daily for several years. “He talked a lot about retrieving stuff from the salt mines outside Salzburg, I think,” a former student says with the vagueness typical of all who were asked. “That’s disheartening, but it doesn’t surprise me,” says Robert Edsel of the Monuments Men Foundation. He has interviewed the few remaining veterans of MFAA — just nine of the 350 survive — and he travels the country giving talks about their unsung achievements, which the soldiers were usually too humble to brag about themselves. “Sometimes their own families didn’t know what they had done,” says Yeide.

The general amnesia about Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives seems unfortunate, especially among art historians, whose livelihood comes from studying and interpreting the works their predecessors bravely rescued (two Monuments Men were killed in combat). We all owe them a great debt, Edsel believes — “for saving these great cultural treasures that people now travel the world to go see” and then for coming home and helping America go from “cultural backwater to cultural epicenter” in the 1950s. That trajectory continues today, when the students of MFAA men occupy key positions in scores of museums and universities nationwide. In 1945, amid widespread destruction and horror, a few khaki-clad lovers of art lit a small flame of humanity amid the ashes by helping to safeguard great masterpieces. That’s a proud legacy well worth recalling.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 wrote his senior thesis under MFAA veteran Robert Koch *54 and subsequently taught art history at Delaware, Johns Hopkins, and Princeton.

3 Responses

Richard T. Arndt ’49

10 Years AgoA study in contrasts

Compliments on your editorial guile in preceding the splendid article on Princeton’s contribution to the preservation, recovery, repair, and return of the art heritage of Europe in World War II with the inspiring story of ex-Congressman James Leach ’64’s planned tour of all 50 states to plead the cause of civility, from his eminence as chair of the U.S. Endowment for the Humanities (features, June 2).

In case any reader missed the connection, let me spell it out. In 1942, representatives of the museum and art history world, including Princeton’s Rufus Morey, visited FDR to plead for the protection of Europe’s cultural heritage. The president took immediate action, set up a committee of scholars chaired by Justice Stone, instructed the various branches of the military to add young art historians like Princeton’s Craig Smyth ’38 *56 and Joe Kelleher *47 to their ranks and assigned them the towering job of preserving European art, with instructions that the military support them in every way possible. The episode marks a not un-typical moment in U.S. history when cultural values were protected against the unavoidable “hot rake of war,” in Churchill’s phrase. It was an act of decency and civility, recognizing that war was an aberration against which civilized nations had assumed the duty to limit damage to the treasures of the past, representing as much to the U.S. as they did to Europe.

Sixty years later, six months before the U.S. incursion into the cradle of civilization, the lands between the Tigris and Euphrates, where uncounted millions of artifacts still lie buried, a similar delegation visited the president and were received politely. A seven-volume study prepared by the State Department, including detailed instructions on cultural and historical preservation, was delivered in the following weeks to the Department of Defense, led by a Princetonian; the volumes were rejected and their authors chastised. The result: the destruction of the great museum collections of Baghdad, the trashing of the national library, the paving over of archeological sites for airstrips, the dispersal of the professional museum and library staff under terrorist threat, and the appearance in international antiquities markets of thousands of unique artifacts and texts.

Godspeed to Chairman Leach.

William T. Mann ’63

10 Years AgoSaving art treasures

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88’s article (feature, June 2) was an interesting contribution to the ongoing saga of works of art lost and found as a result of World War II. The role of Princeton art experts as “Monuments Men” was especially gratifying.

It seemed strange to me that absolutely no mention was made of Lynn Nicholas, whose exhaustively researched 1994 book, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War, first brought this story to a wide audience. This critically acclaimed nonfiction work was adapted for a documentary of the same name in 2006, which appeared on public television.

George B. Chapman ’50 *52

10 Years AgoErrors in reporting ranks

This World War II vet could not refrain from correcting the double error in the caption to the “Monuments Men” photo in the June 2 issue. Ernest DeWald *14 *16 wears the insignia of a lieutenant colonel, not a lieutenant. (That error is corrected in the text.) Perry Cott ’29 wears the sleeve stripes of a lieutenant commander, not a lieutenant. As Cmdr. Cott was not mentioned in the text (of the otherwise splendid article by W. Barksdale Maynard ’88), it is more important to correct that error. I’m sure that DeWald and Cott would be pleased to know that a mere U.S.N.R. EM 3/C wanted them to be properly ranked.

Please keep up the splendid work on PAW.